White Ash (Fraxinus americana)

Fraxinus americana, the White Ash, is one of the great native forest trees of eastern North America — a majestic, broadly spreading deciduous tree that was, until the catastrophic arrival of the Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis), one of the most abundant and ecologically important trees of the eastern hardwood forest. Its straight, strong timber was the choice wood for tool handles, baseball bats, oars, and sports equipment for generations. Its spectacular purple fall color, host-plant relationships with butterflies, and seed production for birds made it an essential component of the eastern woodland ecosystem from the Maritimes to the Gulf Coast.

The devastating spread of the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB), an invasive beetle from Asia first detected in North America in 2002, has killed tens of millions of ash trees across the eastern United States and Canada, fundamentally changing the landscape in forests where White Ash was once dominant. In many areas of New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, the tall, grey-barked White Ash that once graced roadsides, woodlands, and floodplain forests has been reduced to standing ghost trees or cleared stumps. The ecological and cultural loss is incalculable.

Yet White Ash is not gone, and planting it is not without purpose. In areas where EAB-resistant or partially resistant trees are being selected for breeding programs, and in locations where biocontrol releases of EAB parasitoid wasps are showing effectiveness, White Ash populations may recover in coming decades. The tree’s exceptional ornamental qualities, wildlife value, and cultural heritage make it worth including in native plant gardens alongside EAB management strategies — and its role as a host plant for numerous butterflies and moths cannot be replaced by any other species.

Identification

White Ash is a large, fast-growing deciduous tree reaching 75–120 feet tall at maturity, with a straight trunk and a broadly oval to rounded crown. The trunk can reach 2–5 feet in diameter on old-growth trees. It has a single, dominant central leader and well-spaced, ascending branches that create an open, airy crown structure.

Bark

The bark of mature White Ash is one of its most distinctive identification features. It is dark gray, with a distinctive, interlaced diamond (or basket-weave) pattern of ridges and furrows — one of the most beautiful and recognizable bark patterns of any eastern tree. Young trees have smooth, gray bark; the diamond pattern develops as trees age. The tight, interlacing diamond pattern distinguishes White Ash bark from the more plate-like or shallowly furrowed bark of Green Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), the most commonly confused species.

Leaves

The leaves are pinnately compound — opposite on the stem (critical diagnostic feature for ash) — and typically 8–15 inches long with 5–9 leaflets (usually 7). Leaflets are 3–5 inches long, ovate to elliptical, with a pointed tip, an entire or shallowly toothed margin, and a pale glaucous (whitish-blue) underside that gives the species its common name “white.” Grasping the leaf stem and rubbing the leaflet undersurface leaves a characteristic whitish residue. In autumn, the foliage turns magnificent shades of purple, maroon, burgundy, and golden yellow — among the finest fall color of any native eastern tree. The opposite, compound leaf arrangement is diagnostic for ash; no other common eastern tree has opposite compound leaves except ash species.

Flowers & Seeds

White Ash is dioecious — male and female flowers on separate trees. Flowers appear in spring before or with the leaves, in small, inconspicuous clusters. The seeds are single-winged samaras (the paddle-shaped “helicopter” seeds familiar from many ash trees), 1–2 inches long, hanging in dense clusters from female trees. The seeds ripen in fall and persist on the tree through much of winter, providing food for birds before falling in early spring. The seeds are produced in prodigious quantities by large, mature trees — a single White Ash can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds annually.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Fraxinus americana |

| Family | Oleaceae (Olive) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 75–120 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Greenish-purple (small, clustered) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

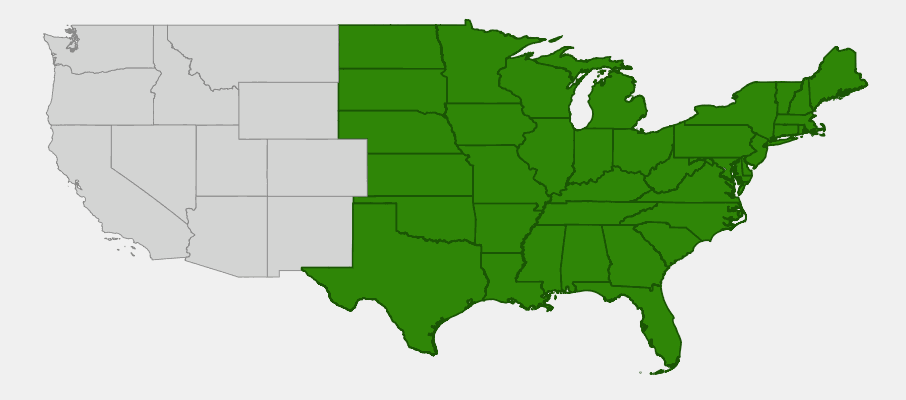

White Ash has one of the broadest natural ranges of any eastern North American tree, occurring from Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island south to northern Florida and west to Minnesota, Nebraska, and Texas. It was formerly one of the most abundant large forest trees of the eastern deciduous forest, particularly in the rich, moist-to-mesic upland forests of the Appalachians, Ohio Valley, and Great Lakes region where it achieved its greatest size and ecological dominance.

In New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, White Ash was historically a component of virtually every upland forest community, from the rich mixed-hardwood forests of the Appalachian highlands to the cove forests of the Catskills and Pocono Plateau. It was particularly common on mesic slopes, in rich bottomlands, and in mixed forests with Sugar Maple, Yellow Birch, and American Beech. The species showed remarkable adaptability across a wide range of soil types, from moist, rich loams to drier, rocky slopes.

The Emerald Ash Borer has now colonized virtually the entire native range of White Ash in the United States and Canada, killing trees of all ages and sizes. In many forests of the tri-state region, the forest composition is being fundamentally altered by the loss of ash — creating large gaps in the canopy and shifting successional dynamics in ways that will take generations to fully resolve. Biocontrol agents (parasitoid wasps) are being released and show promise, but large-scale recovery of ash populations is uncertain.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring White Ash: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

White Ash is a vigorous, adaptable native tree that — in the absence of the Emerald Ash Borer — is among the easiest large forest trees to establish. With EAB management now a key consideration, planting strategy should include awareness of regional EAB biocontrol status and monitoring.

Light

White Ash grows best in full sun to part shade. It tolerates more shade than many other large forest trees, making it suitable for woodland edge plantings and partially shaded situations. In full sun, it develops the densest, most vigorous crown and the best fall color. In part shade, growth is adequate but the fall purple-to-gold color may be somewhat less intense. As a young tree, it shows reasonable shade tolerance, establishing under partial canopy before the crown emerges into full light.

Soil & Water

White Ash is adaptable to a wide range of soil conditions — from moist, rich loams to drier, well-drained soils on rocky slopes. It grows best on deep, moderately moist, well-drained soils but tolerates considerable variation. Unlike many other species in this batch, White Ash prefers average moisture (neither wet nor drought conditions) and performs well on the typical garden or lawn soil of the northeastern United States. It tolerates moderately acidic to slightly alkaline soils. Avoid poorly drained, waterlogged sites — White Ash is not a wetland species.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring or fall in a location with good sun and well-drained soil. White Ash transplants readily from container or balled-and-burlapped stock. Space trees at least 30 feet from other large trees and structures to allow for the full, spreading crown. If planting in areas with active EAB infestation, consult with your state’s forestry department about biocontrol releases and management options. In some areas, systemic insecticide treatment can protect individual high-value trees from EAB, though this requires ongoing annual treatment and is most practical for trees of significant value near buildings.

Pruning & Maintenance

White Ash requires minimal routine pruning — remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while the tree is dormant. The strong wood and well-structured crown make it a low-maintenance tree in terms of storm damage. Monitor regularly for signs of Emerald Ash Borer infestation: S-shaped galleries under the bark, D-shaped exit holes (⅛ inch), crown dieback starting at the top, and woodpecker damage (indicating beetle activity beneath bark). Early detection allows for treatment options; late-stage infestation typically results in rapid decline and tree death.

Landscape Uses

- Large shade tree for spacious properties and parks

- Street tree in areas with active EAB biocontrol programs

- Woodland restoration of mesic upland forest communities

- Fall color anchor — spectacular purple, maroon, and gold autumn foliage

- Wildlife habitat anchor for butterfly larvae and seed-eating birds

- Cultural and historical landscapes where ash was historically dominant

- Timber plantings for sustainable wood production on appropriate sites

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Before the EAB crisis, White Ash was one of the most ecologically productive trees of the eastern hardwood forest. Its ecological contributions — while now diminished by widespread mortality — are irreplaceable by any other single species.

For Birds

The abundant single-winged samaras (seeds) of White Ash are consumed by a remarkable diversity of bird species including Evening Grosbeaks, Purple Finches, Pine Grosbeaks, American Goldfinches, White-winged Crossbills, Wild Turkeys, and Wood Ducks. The seeds ripen in fall and persist on the tree through winter, providing critical high-energy food during periods when other seeds are buried under snow. The large canopy of mature White Ash provides nesting habitat for Red-tailed Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks, Baltimore Orioles, and many other species. Baltimore Orioles famously favor the drooping outer branches of tall ash trees for their pendulous, woven nests.

For Mammals

Deer, squirrels, rabbits, and chipmunks consume White Ash seeds and browse the foliage. Porcupines chew the outer bark of living trees in winter (a potential health concern for individual trees). Beavers harvest ash for dam building and food. The deep, furrowed bark provides overwintering habitat for various insects including beetles and moths, which in turn support insectivorous bats and birds.

For Pollinators

White Ash is a critical larval host plant for the Tiger Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio glaucus), the Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa), and over 150 other Lepidoptera species. The Tiger Swallowtail is one of the most conspicuous and beloved native butterflies, and its dependence on ash as a primary larval host plant makes the survival of ash populations ecologically critical for this species. The flowers provide early-season pollen for native bees and other pollinators.

Ecosystem Role

White Ash was a foundational canopy species in the eastern mixed hardwood forest, providing dense shade that shaped the forest floor plant community, leaf litter that enriched the soil, and structural complexity that supported hundreds of other species. Its rapid loss to EAB is creating dramatic ecological disruption — sudden canopy gaps, altered light regimes, and the loss of a key larval host for several butterfly species. Understanding and documenting this loss is critical for conservation biology and forest management in the eastern United States.

Cultural & Historical Uses

White Ash wood is among the most celebrated of all North American timber species. Its exceptional combination of strength, flexibility, hardness, and shock resistance — qualities shared by no other wood in such measure — made it the choice material for tool handles (axes, shovels, rakes, hoes), sporting goods (baseball bats, hockey sticks, oars, paddles, lacrosse sticks), furniture, flooring, and cabinetry. The Major League Baseball requirement that bats be made from solid wood ensured that ash forests in northern Pennsylvania and New York were managed specifically for baseball bat production through much of the 20th century.

Indigenous peoples throughout the eastern woodlands used White Ash for a remarkable range of purposes. The Iroquois, Cherokee, Ojibwe, and many other nations used ash wood for tool handles, snowshoe frames, basket making (particularly splint baskets made by pounding ash logs to separate annual growth rings), and ceremonial objects. The inner bark was used medicinally as a laxative, diuretic, and treatment for fever. The seeds were ground and used as food. Some nations used ash bark in preparation of ceremonial body paint and in purification rituals. Ash splint basket making remains an important living craft tradition among Wabanaki peoples of New England and the Maritime provinces.

The commercial timber industry valued White Ash as one of the premier furniture and flooring woods of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Major ash forests in Appalachia, the Midwest, and the Great Lakes region were logged extensively. The wood’s beauty, workability, and durability made it valuable for furniture, interior trim, church pews, and sports floors. Today, with ash populations devastated by EAB, the timber industry has largely shifted to other species, but White Ash remains in demand for specialty applications where its unique mechanical properties cannot be matched.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I plant White Ash given the Emerald Ash Borer threat?

This is a complex question. In areas with active EAB biocontrol programs (parasitoid wasp releases), planting ash may contribute to future population recovery. Some nurseries are beginning to propagate trees from potentially EAB-tolerant seed sources. Consult your state forestry agency for current guidance. For a typical home garden in the Northeast, planting White Ash is a personal decision — some gardeners choose to plant knowing the tree may not reach maturity, valuing its ecological contributions during its years of health.

How do I identify White Ash vs Green Ash?

White Ash (F. americana) has distinctly whitish (glaucous) leaf undersides, a diamond/basket-weave bark pattern, leaflet margins that are entire to shallowly toothed, and leaflets attached to the rachis by obvious stalks (petiolules). Green Ash (F. pennsylvanica) has green leaf undersides without the glaucous bloom, more shallowly furrowed bark, more distinctly toothed leaflets, and leaflets nearly sessile on the rachis.

What is White Ash wood used for today?

Despite EAB losses, White Ash lumber remains available from salvage operations and sustainably managed stands in less-affected areas. It is still used for specialty baseball bats (favored by some players over maple), tool handles, flooring, furniture, and splint basket making. The wood from EAB-killed trees is often salvaged for firewood and lumber before deterioration.

Is White Ash fall color really purple?

Yes — White Ash produces one of the few genuinely purple fall colors of any native eastern tree. The fall display typically progresses from green through yellow to a deep purple-maroon, often with both colors present simultaneously. The intensity varies by individual tree and site conditions; trees in full sun generally show the most vivid purple tones.

What replaces White Ash in the landscape after EAB?

There is no perfect replacement for White Ash’s unique ecological role and cultural value. From a wildlife perspective, Ironwood (Ostrya virginiana), Black Cherry (Prunus serotina), and other species can help fill some of the habitat gap. For Tiger Swallowtail caterpillar food, Tulip Poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) and Wild Black Cherry are the primary alternatives. From a timber perspective, Black Walnut and American Basswood offer some comparable properties for specific uses.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries White Ash?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania