Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum)

Vaccinium corymbosum, commonly known as Highbush Blueberry or Northern Highbush Blueberry, is North America’s most economically important native fruit species and one of the continent’s most beloved wild edibles. This deciduous shrub of the Ericaceae (heath) family represents a remarkable conservation success story — transforming from a humble woodland understory plant into the foundation of a multi-billion-dollar agricultural industry, while simultaneously remaining a cornerstone species for native wildlife and natural ecosystems throughout eastern North America.

Growing naturally in acidic soils from southern Canada to northern Florida, Highbush Blueberry typically reaches 6 to 12 feet tall, forming dense colonies through underground rhizomes that create extensive natural berry patches in swamps, bogs, and moist woodlands. The species’ distinctive features include smooth, grayish bark, simple oval leaves that turn brilliant orange-red in autumn, delicate white to pinkish bell-shaped flowers in spring, and of course, the sweet, dark blue berries that have sustained both Indigenous peoples and wildlife for millennia.

What makes Highbush Blueberry particularly remarkable is its dual role in both wild and cultivated landscapes. While commercial varieties have been bred for larger fruit and extended harvest seasons, wild populations continue to provide essential habitat and food resources for over 40 species of birds, numerous mammals, and countless pollinators. The plant’s ecological value extends far beyond its fruit — its dense growth provides critical nesting sites, its flowers support early-season pollinators when few other native plants are blooming, and its extensive root systems help stabilize soils in riparian areas and wetland edges throughout its range.

Identification

Highbush Blueberry is a multi-stemmed deciduous shrub that typically grows 6 to 12 feet tall, though exceptional specimens in optimal conditions can reach up to 15 feet. The plant often forms extensive colonies through underground rhizomes, creating natural blueberry patches that can span several acres in favorable habitats. The overall growth habit is upright and somewhat spreading, with younger stems growing vertically while older canes arch outward under the weight of fruit and foliage.

Bark & Stems

The bark is one of Highbush Blueberry’s most distinctive features — smooth and grayish on mature stems, often with a slight reddish tinge on younger growth. As stems age, the bark develops shallow fissures and may peel in thin, papery strips. Young twigs are green to reddish-brown, becoming grayish with age. Unlike many shrubs, Highbush Blueberry rarely develops a true trunk, instead producing multiple stems from the base that give it a fountain-like appearance. The canes are long-lived, often persisting for 10-15 years before being replaced by new growth from the root system.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and elliptical to oval in shape, measuring 1.5 to 3.5 inches long and 0.75 to 1.5 inches wide. They have a distinctive smooth, waxy texture with entire (smooth) margins and a prominent midrib. The upper surface is dark green and glossy, while the underside is paler green, sometimes with a slightly grayish cast. Venation is pinnate, with 4-6 pairs of lateral veins that curve toward the leaf tip. The petioles (leaf stems) are short, typically less than ¼ inch long, and often reddish in color. In autumn, the foliage transforms into brilliant shades of orange, red, and yellow, making Highbush Blueberry one of the most spectacular fall-color shrubs in eastern forests.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers appear in early to mid-spring, before the leaves are fully expanded, in drooping clusters (racemes) of 5-10 individual flowers at the tips of branches. Each flower is bell-shaped (campanulate), about ¼ to ⅓ inch long, and typically white to pale pink in color. The corolla has five shallow lobes that curve backward, revealing the flower’s interior and making the nectar accessible to various pollinators. The flowers have a subtle, sweet fragrance that attracts native bees, particularly bumblebees, which are the primary pollinators. Each flower contains both male and female parts, though the species benefits significantly from cross-pollination.

The fruit is a many-seeded berry that develops from midsummer to early fall, depending on the variety and geographic location. Wild berries are typically smaller than cultivated ones, ranging from ¼ to ½ inch in diameter, though some wild populations produce surprisingly large fruit. The berries ripen from green to red to deep blue-black, with a distinctive powdery bloom (waxy coating) that gives them a dusty appearance. At the tip of each berry is a small crown — the persistent sepals from the flower — which is a key identifying feature distinguishing true blueberries from similar-looking fruits like huckleberries.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Vaccinium corymbosum |

| Family | Ericaceae (Heath) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 6–12 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | White to pale pink |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–7 |

Native Range

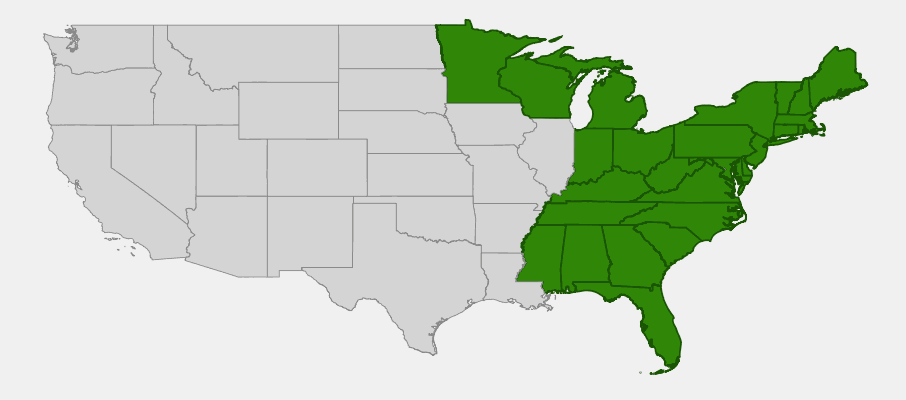

Highbush Blueberry has one of the largest native ranges of any North American fruit species, extending from southeastern Canada south to northern Florida and west to the Great Lakes region. The species is native to the eastern deciduous forests, occurring naturally in 26 U.S. states plus southeastern Canada. This extensive range reflects the species’ remarkable adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, from the harsh winters of northern Minnesota and Maine to the mild subtropical conditions of northern Florida and the Gulf Coast.

Throughout its range, Highbush Blueberry typically occurs in acidic, organic-rich soils with consistent moisture — habitats that include bogs, swamps, wetland edges, acidic seeps, and the understory of mixed hardwood-conifer forests. The species shows a strong preference for areas with seasonal water level fluctuations, thriving in locations that are saturated in winter and spring but become merely moist (never dry) during summer months. This habitat preference explains why wild blueberry patches are often found along pond margins, in seasonal wetlands, and in forest openings where water collects.

Historically, Indigenous peoples throughout Highbush Blueberry’s range recognized and managed wild populations through controlled burning and selective harvesting. Many of the “natural” blueberry barrens and extensive wild patches found today are actually the result of centuries of careful stewardship by Native American communities who understood the species’ fire ecology and used prescribed burns to maintain productive berry-picking areas.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Highbush Blueberry: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Highbush Blueberry is surprisingly adaptable and easier to grow than many people assume, provided you understand its fundamental requirements: acidic soil, consistent moisture, and good drainage. Success with this species comes down to recreating the conditions found in its natural habitat — the acidic, organic-rich soils of bogs and woodland edges where water is plentiful but never stagnant.

Light

Highbush Blueberry performs best in full sun to partial shade, with at least 6 hours of direct sunlight producing the heaviest fruit crops and most compact growth. In full sun, plants develop denser branching, better flowering, and superior fall color, though they require more consistent watering. In partial shade (4-6 hours of sun), plants grow taller and more open but still produce good crops of berries. The species is surprisingly shade-tolerant and can survive in deeper shade, though fruit production drops significantly. In northern climates, full sun is generally preferred; in hot southern regions, afternoon shade can be beneficial.

Soil & Water

Soil chemistry is critical for Highbush Blueberry success. The species requires acidic soil with a pH between 4.5 and 5.5 — more acidic than most other fruiting plants can tolerate. This acid requirement isn’t optional; in neutral or alkaline soils, plants develop chlorosis (yellowing leaves) and eventually decline, regardless of fertilization. The soil should also be rich in organic matter, well-draining but moisture-retentive, and loose-textured to allow for proper root development.

Water needs are consistently high throughout the growing season. Highbush Blueberry has a shallow, fibrous root system (most roots are in the top 8 inches of soil) that cannot reach deep groundwater like trees can. Plants need about 1-2 inches of water per week, either from rainfall or irrigation, with particular attention during fruit development and hot weather. Mulching with 3-4 inches of organic matter (pine bark, pine needles, or shredded leaves) is essential to maintain soil moisture and gradually acidify the soil as it decomposes.

Planting Tips

Plant Highbush Blueberry in early spring or fall when temperatures are moderate. If your natural soil isn’t acidic enough, create raised beds or large planting holes filled with a mixture of peat moss, compost, and existing soil. Space plants 4-6 feet apart for hedgerow plantings or 6-8 feet apart for specimen plants. Choose varieties appropriate to your hardiness zone and consider planting multiple varieties to extend the harvest season and improve cross-pollination.

When purchasing plants, look for 2-3 year old specimens from reputable nurseries specializing in native or edible plants. Container-grown plants establish more reliably than bare-root ones. After planting, remove any flowers during the first year to help plants establish strong root systems before putting energy into fruit production.

Pruning & Maintenance

Proper pruning is essential for maintaining productive Highbush Blueberry bushes. During the dormant season (late winter), remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches, and thin out weak or spindly growth. On mature bushes (5+ years old), remove 1-2 of the oldest canes annually to encourage new growth from the base. This renewal pruning maintains vigor and prevents bushes from becoming too dense and unproductive.

Avoid heavy pruning in a single year — spread major renovation over 2-3 seasons. Never prune during the growing season unless removing dead or damaged wood, as this reduces the current year’s fruit crop and next year’s flower buds. Young plants (under 4 years) need minimal pruning beyond removing dead wood and maintaining shape.

Landscape Uses

Highbush Blueberry offers exceptional versatility in landscape design:

- Edible landscapes — produces delicious fruit while providing ornamental value

- Wildlife gardens — supports numerous bird species and pollinators

- Native plant gardens — perfect for woodland edge and naturalistic plantings

- Rain gardens — tolerates seasonal flooding and helps filter runoff

- Screening and hedgerows — dense growth provides year-round privacy

- Acidic soil areas — thrives where other fruiting plants struggle

- Fall color displays — spectacular orange-red autumn foliage

- Foundation plantings — attractive four-season structure near homes

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native plants rival Highbush Blueberry in terms of wildlife value. This species functions as a critical food source, nesting habitat, and shelter provider throughout its extensive range, supporting an remarkable diversity of creatures from tiny native bees to large mammals.

For Birds

Over 40 species of birds are known to consume Highbush Blueberry fruit, making it one of the most important native food sources in eastern North America. Major consumers include American Robins, Eastern Bluebirds, Cedar Waxwings, Gray Catbirds, Brown Thrashers, Northern Cardinals, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Scarlet Tanagers, and numerous warbler species. Game birds such as Ruffed Grouse, Wild Turkey, and various waterfowl species also rely heavily on the berries, particularly during fall migration and winter months.

Beyond fruit consumption, Highbush Blueberry provides essential nesting habitat for many songbird species. The dense, multi-stemmed growth form creates excellent cover and nesting sites 3-8 feet above ground — the perfect height for many forest-edge species. American Robins, Gray Catbirds, and various vireo species commonly build nests within blueberry thickets, where the thorny nature of some associated plants and the dense branching provide protection from predators.

For Mammals

Virtually every fruit-eating mammal within Highbush Blueberry’s range consumes the berries. Black Bears are perhaps the most notable consumers, often traveling significant distances to reach productive blueberry patches during the late summer fruiting season. White-tailed Deer browse both fruit and foliage, though heavy deer pressure can damage or eliminate blueberry populations in some areas.

Smaller mammals including raccoons, opossums, foxes, coyotes, chipmunks, and various mice and voles all consume the fruit and help disperse seeds. The berries are particularly important for fall and winter wildlife nutrition, as they remain on bushes well into autumn and provide concentrated energy for animals preparing for winter or migration.

For Pollinators

Highbush Blueberry flowers are specifically adapted for bee pollination, and over 115 species of native bees are known to visit them. The flowers’ bell shape requires “buzz pollination” — a specialized technique where bees grab the flower and vibrate their flight muscles to shake pollen loose. Bumblebees are particularly effective at this technique and are the primary pollinators, though mason bees, mining bees, and sweat bees also play important roles.

The early bloom time (April-May in most areas) makes Highbush Blueberry flowers critically important for emerging queen bumblebees and other early-season pollinators when few other native plants are flowering. A single mature blueberry bush can produce thousands of flowers, creating a significant nectar and pollen resource during a typically resource-poor time of year.

Ecosystem Role

In natural ecosystems, Highbush Blueberry functions as what ecologists call a “foundation species” — a plant that creates habitat structure and resources that many other species depend on. The dense thickets formed by mature blueberry colonies provide crucial cover for small mammals, ground-nesting birds, and reptiles. The leaf litter beneath blueberry bushes supports diverse invertebrate communities, which in turn feed numerous bird and salamander species.

The species also plays an important role in nutrient cycling and soil chemistry. As an ericaceous plant with specialized mycorrhizal associations, Highbush Blueberry helps maintain the acidic soil conditions that many other native plants in its community require. The plant’s extensive, shallow root system helps prevent soil erosion, particularly important in its natural riparian and wetland edge habitats.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Highbush Blueberry holds a place of special significance in North American cultural history, representing one of the continent’s most important indigenous food plants and a remarkable example of successful crop domestication. For thousands of years before European contact, Indigenous peoples throughout eastern North America relied on wild blueberries as a crucial food source, developing sophisticated management techniques and preservation methods that sustained communities through harsh winters.

The Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and other Northeastern tribes called blueberries “star berries” because of the five-pointed crown at each fruit’s tip, believing they were sent by the Great Spirit during times of famine. The Ojibwe and other Great Lakes peoples incorporated blueberries into pemmican — a concentrated, portable food made from dried meat, fat, and berries that could sustain hunters and travelers for weeks. Throughout the Southeast, Cherokee, Creek, and other tribes managed extensive wild blueberry patches through controlled burning, creating open, productive “barrens” that could yield massive harvests.

These traditional burning practices weren’t simply harvesting techniques — they represented sophisticated ecological management that increased blueberry productivity while maintaining diverse plant communities. By burning on 3-5 year cycles, Indigenous peoples eliminated competing vegetation, returned nutrients to the soil, and stimulated new growth from blueberry root systems, creating more productive and accessible berry-picking areas than existed in undisturbed forests.

European colonists initially struggled to appreciate blueberries, finding them inferior to familiar European fruits. However, as settlements expanded and traditional food systems broke down, especially during times of conflict and hardship, colonists learned to rely on blueberries as their Indigenous neighbors had for centuries. By the late 1800s, commercial harvesting of wild blueberries had become an important industry in Maine, New Jersey, and other areas with extensive natural populations.

The transformation of Highbush Blueberry from wild food to agricultural crop began in the early 1900s with the work of Elizabeth White, a New Jersey cranberry farmer, and Frederick Coville, a USDA botanist. White offered bounties to local residents who could locate wild bushes with the largest, best-tasting berries, while Coville developed propagation and breeding techniques. Their collaboration resulted in the first cultivated blueberry varieties in 1916, launching what would become a multi-billion-dollar industry.

Today, cultivated blueberries are grown on six continents, but the industry still relies heavily on the genetic diversity of wild North American populations. Modern breeding programs continue to incorporate genes from wild Highbush Blueberry populations to improve disease resistance, extend harvest seasons, and adapt varieties to different climatic conditions. This ongoing dependence on wild genetic resources highlights the importance of conserving natural blueberry populations and their ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are wild blueberries safe to eat, and how can I identify them?

Yes, wild Highbush Blueberries are completely safe and delicious to eat. The key identifying features are the five-pointed crown (star shape) at the tip of each berry, the blue-black color with powdery bloom, and the characteristic oval leaves and bell-shaped flowers. Always be 100% certain of identification before consuming any wild berry, and avoid harvesting from areas that might be contaminated by pesticides or pollution.

Can I grow blueberries in regular garden soil?

Probably not successfully without soil modification. Highbush Blueberries absolutely require acidic soil (pH 4.5-5.5) to thrive. In neutral or alkaline soils, plants develop iron chlorosis and gradually decline. Test your soil pH first — if it’s above 6.0, you’ll need to create raised beds with acidic planting mix or use containers filled with acidic potting soil designed for blueberries and azaleas.

How long before blueberry plants produce fruit?

Container-grown plants typically begin producing small crops in their second or third year after planting, reaching full production by years 5-6. However, it’s recommended to remove flowers during the first year to help plants establish strong root systems. Mature, well-maintained bushes can remain productive for 30-50 years or more, making them excellent long-term investments.

Do I need multiple plants for fruit production?

While Highbush Blueberries are self-fertile (a single plant can produce fruit), you’ll get much larger crops and better berry quality with cross-pollination from multiple varieties. Plant at least two different varieties that bloom at the same time for optimal results. This also extends your harvest season, as different varieties ripen at different times throughout the summer.

Why are my blueberry leaves turning yellow?

Yellowing leaves (chlorosis) is almost always a sign of soil pH problems — the soil is too alkaline for the plant to absorb iron effectively. Test your soil pH and lower it if necessary using sulfur or acidic organic matter. Other possible causes include overwatering, underwatering, or nutrient deficiencies, but pH issues are by far the most common cause of yellowing in blueberries.

Looking for a nursery that carries Highbush Blueberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina