Ironwood (Ostrya virginiana)

Ostrya virginiana, commonly known as Ironwood, American Hophornbeam, or Eastern Hophornbeam, is a small to medium-sized deciduous tree native to eastern North America. This member of the Betulaceae (birch) family is renowned for its exceptionally hard, dense wood that gave it the name “ironwood” — wood so tough it was historically used for tool handles, fence posts, and other applications requiring extreme durability.

Found naturally in understory and edge habitats from Nova Scotia to northern Florida and west to southeastern Saskatchewan and eastern Texas, Ironwood is a slow-growing but long-lived tree that typically reaches 25 to 40 feet tall. Its distinctive shreddy, fibrous bark peels in thin vertical strips, while its hop-like fruiting clusters (technically called strobiles) make it easily recognizable among native trees. The small, hard nutlets are an important food source for many birds and small mammals.

Despite being understudied compared to more prominent forest trees, Ironwood plays a crucial ecological role as an understory species, providing food and habitat structure in mature deciduous and mixed forests. Its tolerance for shade, drought, and poor soils, combined with its attractive appearance and manageable size, makes it an excellent choice for native plant gardens, naturalized landscapes, and woodland restoration projects throughout its range.

Identification

Ironwood is typically a small understory tree, growing 25 to 40 feet tall with a trunk diameter of 8 to 18 inches, though exceptional specimens can reach 60 feet. The crown is usually narrow and rounded, with slender, drooping branches that give the tree a somewhat weeping appearance. Young trees often grow as large shrubs with multiple stems before developing a single trunk.

Bark

The bark is Ironwood’s most distinctive feature. On mature trees, it becomes gray-brown and develops characteristic vertical strips that peel and shred, giving it a fibrous, “muscular” appearance — hence another common name, “Muscle Wood.” Young bark is smooth and gray, while older bark becomes increasingly furrowed and scaly. The inner bark is reddish-brown.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and oval to elliptical, measuring 2 to 5 inches long and 1 to 3 inches wide. They have sharp double serrations along the margins and prominent parallel veins that give them a pleated texture similar to birch leaves. The upper surface is dark green and smooth, while the underside is paler and slightly hairy along the veins. Fall color ranges from yellow to orange-brown.

Flowers & Fruit

Ironwood is monoecious, producing separate male and female flowers on the same tree. Male flowers appear in long, drooping catkins 1 to 4 inches long in early spring before the leaves emerge. Female flowers are smaller and less conspicuous. The fruit develops into distinctive papery, hop-like clusters (strobiles) that hang from the branches in late summer and fall, each containing small, hard nutlets about ¼ inch long.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Ostrya virginiana |

| Family | Betulaceae (Birch) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 30–50 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

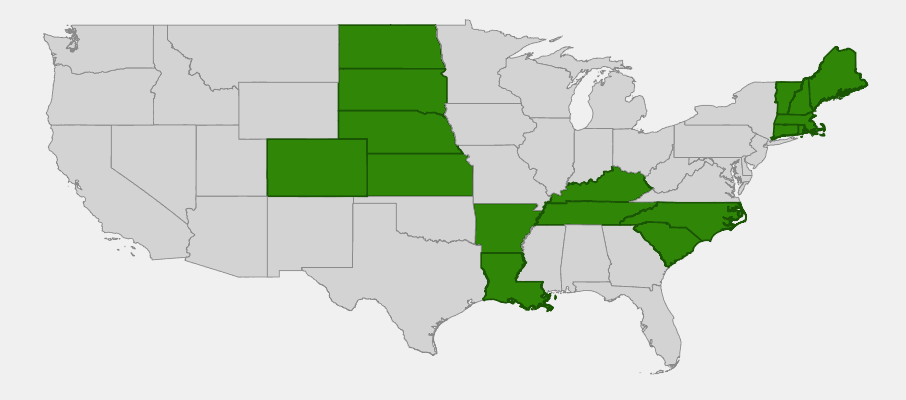

Ironwood has one of the broadest distributions of any North American hardwood tree, ranging from Nova Scotia and southern Quebec west to southeastern Saskatchewan and eastern Wyoming, and south to northern Florida and eastern Texas. This extensive range reflects the species’ remarkable adaptability to diverse climatic conditions, from the humid forests of the Southeast to the drier woodlands of the Great Plains.

Throughout this range, Ironwood typically grows as an understory tree in mature deciduous and mixed forests, often associated with oak-hickory, maple-basswood, and beech-maple forest communities. It shows a preference for well-drained upland sites but can also be found in floodplains and along streams. The species is particularly common in the Appalachian Mountains and the forests of the upper Midwest and Great Lakes region.

In the southeastern portion of its range, including North Carolina and South Carolina, Ironwood is most commonly found in the mountains and upper Piedmont, where it grows in cove forests and on north-facing slopes alongside other mesophytic species like tulip poplar, basswood, and sugar maple.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Ironwood: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Ironwood is an excellent native tree for challenging sites, offering exceptional tolerance for shade, drought, and poor soils once established. While it’s slow-growing compared to many other native trees, its longevity and low maintenance requirements make it a worthwhile investment for patient gardeners.

Light

One of Ironwood’s greatest assets is its exceptional shade tolerance — it’s among the most shade-tolerant hardwood trees in North America. It grows well in everything from full sun to deep shade, though growth is slowest in the deepest shade. In full sun, it develops a denser, more compact crown; in shade, it maintains a more open, graceful form. This flexibility makes it ideal for understory plantings or as a specimen tree in partially shaded locations.

Soil & Water

Ironwood adapts to a wide range of soil conditions, from sandy to clay soils, and tolerates both acidic and alkaline conditions (pH 5.0–8.0). It shows good drought tolerance once established, though it performs best with consistent moisture during the growing season. Good drainage is important — avoid sites with standing water or consistently soggy soils. The species is also tolerant of urban conditions, including compacted soils and air pollution.

Planting Tips

Plant Ironwood in fall or early spring. Choose nursery-grown container or balled-and-burlapped specimens, as the species can be difficult to transplant from the wild due to its deep taproot. Space trees 15–25 feet apart for screening, or allow 20–30 feet for specimen plantings. Mulch around newly planted trees to retain moisture and suppress weeds, but keep mulch several inches away from the trunk.

Pruning & Maintenance

Ironwood requires minimal pruning. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while the tree is dormant. The species naturally develops good structure, so structural pruning is rarely needed. Avoid heavy pruning, as Ironwood is slow to recover from major cuts. The tree is generally pest- and disease-free, making it one of the lowest-maintenance native trees available.

Landscape Uses

Ironwood’s adaptability and attractive features make it valuable in many landscape situations:

- Understory planting beneath larger shade trees

- Specimen tree in small yards where space is limited

- Naturalized areas and woodland gardens

- Wildlife habitat — excellent for birds and small mammals

- Urban forestry — tolerates pollution and compacted soils

- Erosion control on slopes and difficult sites

- Screen or hedge when planted in groups

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite being less conspicuous than many other native trees, Ironwood provides significant ecological value, particularly as a food source and nesting habitat for wildlife.

For Birds

The small, hard nutlets are consumed by at least 15 species of birds, including Wild Turkey, Ruffed Grouse, Ring-necked Pheasant, and various songbirds such as Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Purple Finch, and Downy Woodpecker. The dense, twiggy structure of the crown provides excellent nesting sites for small birds, while the hop-like clusters remain on the tree well into winter, providing food during the lean months.

For Mammals

Small mammals including chipmunks, squirrels, and mice cache the nutritious nutlets for winter food. White-tailed deer browse the twigs and young bark, especially in winter when other food sources are scarce. The thick, shreddy bark provides nesting material for small mammals and roosting sites for bats.

For Pollinators

The early spring catkins provide pollen for native bees and other early-emerging insects when few other food sources are available. While the flowers are wind-pollinated and not particularly showy, they still contribute to the early-season nectar flow that supports pollinator communities.

Ecosystem Role

As an understory tree, Ironwood contributes to forest structural diversity and helps create the multi-layered canopy that supports diverse wildlife communities. Its slow decomposition rate means fallen logs persist in the forest ecosystem for decades, providing habitat for fungi, insects, and other decomposer organisms. The deep taproot helps stabilize soil and access deep water and nutrients, making them available to other plants through mycorrhizal networks.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Ironwood earned its common name from its extraordinarily hard, dense wood — among the hardest of any North American tree. Indigenous peoples throughout its range utilized this remarkable material for tools and implements requiring extreme durability. The Cherokee used ironwood for bows, arrow points, and digging sticks, while other tribes crafted tool handles, war clubs, and fishing implements from the tough wood.

European settlers quickly recognized the value of ironwood for similar applications. The wood was prized for handles of axes, hammers, and other tools, as well as for fence posts, mill machinery, and any application where strength and wear resistance were paramount. Ironwood posts were known to last for decades without rotting, even in contact with soil. The wood’s extreme hardness made it difficult to work — it was said to “eat up” steel tools — but the durability made the effort worthwhile.

In addition to its practical uses, ironwood played a role in traditional medicine. Some Native American groups used bark preparations to treat various ailments, though these uses were less common than with other medicinal trees. The inner bark contains compounds with astringent properties, and preparations were sometimes used to treat diarrhea and other digestive issues.

Today, ironwood’s extreme hardness limits its commercial lumber use, as it’s difficult and expensive to mill. However, it’s still occasionally used for specialty items like tool handles, golf club heads, and decorative woodturning projects. The species is increasingly valued for its ecological benefits and as an attractive, low-maintenance native tree for sustainable landscaping.

Frequently Asked Questions

How fast does Ironwood grow?

Ironwood is a slow-growing tree, typically adding 6–12 inches per year under favorable conditions. While this means it takes longer to reach mature size than faster-growing trees, it also means the wood is extremely dense and the tree is very long-lived, often surviving 100–150 years or more.

Is Ironwood the same as Hop Hornbeam?

Yes, American Hophornbeam and Ironwood are the same tree (Ostrya virginiana). The “hop” name refers to the clusters of papery, hop-like fruits that develop in late summer. “Hornbeam” refers to the hard wood, while “ironwood” also references the wood’s exceptional hardness.

Can you eat Ironwood nuts?

The small nutlets are technically edible but are extremely hard and have very little meat inside the tough shell. They’re much better left for the wildlife that depends on them. The effort required to extract the small amount of nutmeat isn’t worthwhile for human consumption.

Does Ironwood have any pest or disease problems?

Ironwood is remarkably pest- and disease-resistant. It’s rarely bothered by serious insect pests or diseases, making it one of the most trouble-free native trees. This resistance, combined with its adaptability to various growing conditions, makes it an excellent choice for low-maintenance landscapes.

Why is my Ironwood growing so slowly?

Slow growth is normal for Ironwood — it’s one of the slower-growing native trees. However, extremely poor soils, deep shade, or drought stress can further slow growth. Ensure adequate moisture during the first few years after planting, and consider light fertilization in spring if soil is very poor. Remember that slow growth produces extremely strong, long-lived wood.

Looking for a nursery that carries Ironwood?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina