Mountain Winterberry (Ilex montana)

Ilex montana, commonly known as Mountain Winterberry or Large-leaf Holly, is one of the tallest and most impressive native hollies of eastern North America. This deciduous member of the Aquifoliaceae (holly) family can reach heights of 15 to 40 feet, making it significantly taller than its shrubby relatives like Common Winterberry (Ilex verticillata). Endemic to the Appalachian Mountains and surrounding regions, this elegant tree is distinguished by its large, serrated leaves, smooth gray bark, and brilliant red berries that provide crucial winter food for wildlife when other sources are scarce.

Unlike the familiar evergreen American Holly with its spiny leaves, Mountain Winterberry is completely deciduous, dropping its leaves in autumn to reveal clusters of bright red berries on bare branches — a striking winter landscape feature that gives the tree its common name. The species is dioecious, meaning individual trees are either male or female, with only female trees producing the characteristic red berries when pollinated by nearby male trees. The berries persist well into winter, creating a dramatic display against snow and providing essential food for migrating and overwintering birds.

Mountain Winterberry thrives in the moist, well-drained soils of mountain slopes, stream valleys, and forest edges throughout its native range. This adaptable tree tolerates both full sun and partial shade, making it valuable for diverse landscape applications from naturalized woodlands to more formal garden settings. Its relatively fast growth rate, attractive form, exceptional wildlife value, and stunning winter berry display make it an outstanding choice for gardeners seeking a distinctive native tree with four-season interest.

Identification

Mountain Winterberry is easily distinguished from other native hollies by its large size, deciduous habit, and distinctive leaf characteristics. Mature trees develop a narrow, upright crown with a single trunk and ascending branches.

Bark

The bark is one of the most distinctive features, remaining smooth and light gray to silvery-gray throughout the tree’s life. Unlike many trees that develop furrowed or scaly bark with age, Mountain Winterberry maintains its smooth, almost beech-like bark texture. Young twigs are green to reddish-brown and glabrous (smooth), becoming gray with age. The smooth bark creates an attractive winter landscape feature, especially when contrasted with the bright red berries.

Leaves

The leaves are alternate, simple, and notably large for a holly — typically 3 to 6 inches long and 1.5 to 3 inches wide. They are oval to elliptical with a sharply serrated margin, featuring prominent teeth that are much more pronounced than those of most other native hollies. The upper surface is dark green and lustrous, while the underside is paler green. Unlike evergreen hollies, the leaves lack spines and have a softer texture. Fall color is typically yellow to yellow-green before the leaves drop, revealing the berry-laden branches.

Flowers & Fruit

Mountain Winterberry is dioecious, with separate male and female trees. The flowers appear in spring as the leaves emerge, with males producing clusters of small, greenish-white flowers along the branches, while females bear smaller, less conspicuous flowers. The flowers are tiny — about ¼ inch across — but are important early nectar sources for native bees and other pollinators.

The fruit is the tree’s most celebrated feature: bright red drupes about ¼ inch in diameter that appear in dense clusters along the branches. These berries ripen in late summer to early fall and persist well into winter, often remaining on the tree through January or February. Only female trees produce berries, and they require nearby male trees for pollination — typically one male tree can pollinate 6-8 female trees within a 100-foot radius.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Ilex montana |

| Family | Aquifoliaceae (Holly) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 15–40 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | Greenish-white |

| Fruit | Bright red berries (female plants only) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–7 |

Native Range

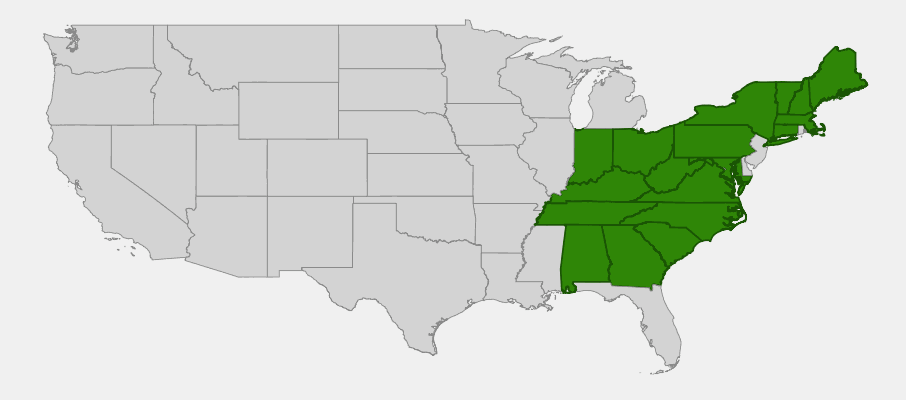

Mountain Winterberry has a broad but somewhat fragmented native range throughout eastern North America, primarily concentrated in the Appalachian Mountain region and extending north into southern Canada. The species occurs from southern Maine and the Maritime Provinces of Canada south through the mountains to northern Georgia and Alabama, with scattered populations in the Great Lakes region and isolated occurrences as far west as Minnesota and Missouri.

This species shows a strong preference for mountainous and upland areas, typically growing at elevations between 1,000 and 4,000 feet throughout most of its range. It is commonly found in moist, well-drained soils along mountain streams, in rich coves, and on north-facing slopes where conditions remain cool and moist. Mountain Winterberry often occurs in mixed hardwood forests dominated by maples, birches, and other mesic species, forming part of the understory and midstory vegetation layers.

Unlike many Appalachian endemics, Mountain Winterberry also extends into the northern portions of its range, occurring in similar habitats in New England and southern Canada. These northern populations often grow in association with boreal forest species and demonstrate the tree’s adaptability to cooler climates. Climate change and habitat fragmentation pose some concerns for scattered populations, particularly those at the southern extremes of the range.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Mountain Winterberry: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Mountain Winterberry is a relatively low-maintenance native tree that adapts well to cultivation, provided its basic needs are met. Understanding its natural habitat preferences is key to success in the garden.

Light

Mountain Winterberry performs well in both full sun and partial shade conditions, showing good adaptability to varying light levels. In full sun, the tree develops a more compact, dense crown and tends to produce more prolific berry displays. In partial shade, it maintains a more open, graceful form and still flowers and fruits well. Avoid deep shade, where flowering and fruiting may be reduced. Morning sun with afternoon shade is ideal in hot climates.

Soil & Water

This tree prefers moist, well-drained, slightly acidic soils with good organic matter content, reflecting its natural mountain habitat. It performs best in soils with a pH between 5.0 and 6.5. While somewhat adaptable to different soil types, Mountain Winterberry struggles in very wet or very dry conditions. Consistent moisture is important, especially during establishment and dry periods. Mulching with 2-3 inches of organic material helps maintain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

Planting Tips

Plant Mountain Winterberry in spring or fall for best establishment. If berry production is desired, be sure to plant both male and female trees — typically one male tree for every 6-8 female trees within 100 feet. Young trees may be purchased as “male” or “female,” though sex cannot be determined until the trees begin flowering at 5-7 years of age. Choose a location with some protection from strong winds, which can damage the smooth bark and break branches.

Pruning & Maintenance

Mountain Winterberry requires minimal pruning and develops an attractive natural form with little intervention. Prune only to remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches, ideally during the dormant season to avoid disrupting berry production. The smooth bark is susceptible to damage from mechanical injury, so use care when mowing or using other equipment near the tree. Established trees are quite drought tolerant but benefit from supplemental watering during extended dry periods.

Landscape Uses

Mountain Winterberry excels in various landscape applications:

- Naturalized woodland gardens — fits naturally into native forest settings

- Specimen tree — attractive form and winter interest

- Mixed borders — provides height and seasonal color

- Stream and pond edges — tolerates moist conditions

- Wildlife gardens — exceptional value for birds

- Winter landscape interest — berries provide color in dormant season

- Native alternatives — replacement for non-native holly species

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Mountain Winterberry provides exceptional wildlife value, particularly as a crucial food source during the challenging winter months when many other food sources have been exhausted.

For Birds

The bright red berries are consumed by over 20 species of birds, including American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Eastern Bluebirds, Northern Mockingbirds, and various thrush species. The berries are particularly important for overwintering birds and early spring migrants, as they persist on the tree well into late winter. The tree’s branching structure provides excellent nesting sites for small to medium-sized songbirds, while the smooth bark may be used by woodpeckers for drumming and foraging.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer occasionally browse the twigs and leaves, while small mammals including chipmunks, squirrels, and mice consume fallen berries. Black bears may eat the berries in areas where the trees grow at higher elevations. The tree’s root system and leaf litter contribute to soil health and provide habitat for numerous small mammals and soil-dwelling creatures.

For Pollinators

The small spring flowers provide an important early-season nectar source for native bees, including mining bees, sweat bees, and various solitary bee species. The flowers also attract beneficial insects such as small wasps and flies that serve as pollinators. While individual flowers are tiny, the collective bloom provides significant resources during the critical spring period when many pollinators are establishing territories and beginning reproduction.

Ecosystem Role

Mountain Winterberry plays an important ecological role in forest edge and understory communities. Its ability to grow in both sun and shade allows it to bridge habitat types, while its winter berry production helps sustain wildlife during the most challenging season. The tree’s leaf litter decomposes relatively quickly, contributing nutrients to forest soils and supporting diverse soil organisms and mycorrhizal networks essential for forest health.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Mountain Winterberry has a long history of use by Indigenous peoples and early European settlers, primarily for its medicinal properties. Various Native American tribes throughout the tree’s range used the inner bark, leaves, and berries for treating different ailments. The Cherokee and other southeastern tribes used bark preparations as treatments for fever, coughs, and digestive issues, while northern tribes including the Iroquois used similar preparations for treating skin conditions and as general tonics.

The tree’s botanical name, Ilex montana, reflects both its holly family relationships and its mountain habitat preferences. Early European botanists were struck by this tall, deciduous holly so different from the familiar evergreen hollies of Europe. The common name “Mountain Winterberry” distinguishes it from the more common shrubby Ilex verticillata (Winterberry Holly), emphasizing both its mountain habitat and its winter fruit display.

During the colonial period and early American settlement, Mountain Winterberry bark was sometimes used as a substitute for imported medicines, particularly during times when trade disruptions made European remedies unavailable. The astringent properties of the bark made it useful for treating wounds and infections, while leaf teas were used for various internal ailments. However, as with many traditional plant medicines, these uses should be considered historical rather than practical applications.

In modern times, Mountain Winterberry has gained recognition primarily as an ornamental tree valued for its wildlife benefits and winter interest. Contemporary landscape designers appreciate its native status, relatively fast growth, and exceptional value for birds. The tree has also become important in ecological restoration projects throughout its native range, helping to reestablish authentic native plant communities and provide crucial wildlife resources in areas where natural habitats have been fragmented or degraded.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell if my Mountain Winterberry is male or female?

You cannot determine sex until the tree begins flowering, typically at 5-7 years of age. Male trees produce more abundant, showier flowers with visible stamens, while female flowers are smaller and less conspicuous. Only female trees will produce berries if pollinated by nearby males.

Do I need both male and female trees to get berries?

Yes, Mountain Winterberry is dioecious and requires cross-pollination. Plant one male tree for every 6-8 female trees within approximately 100 feet for reliable berry production. The male trees also provide valuable flowers for early pollinators.

How long does it take for Mountain Winterberry to produce berries?

Trees typically begin flowering and fruiting at 5-7 years of age, though berry production may be light for the first few years. Full, heavy berry crops usually develop on trees that are 10 years or older.

Are the berries safe for humans to eat?

Like most holly berries, Mountain Winterberry fruits are mildly toxic to humans and can cause digestive upset if consumed in quantity. They should be considered ornamental only and kept away from small children. The berries are, however, an important and safe food source for many bird species.

Can Mountain Winterberry grow in warmer climates?

While native to cooler mountain regions, Mountain Winterberry can adapt to warmer areas within its hardiness range (zones 4-7) if provided with adequate moisture and some protection from intense afternoon sun. However, it may not perform as well in hot, humid climates and is best suited to areas with cool winters.

Looking for a nursery that carries Mountain Winterberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina