Netleaf Hackberry (Celtis reticulata)

Celtis reticulata, commonly known as Netleaf Hackberry, Netleaf Sugar Hackberry, or Western Hackberry, is a tough, drought-adapted native tree of the American West and Southwest. This member of the hemp family (Cannabaceae) earns its common name from the distinctively rough, netted-veined leaves that are one of its most recognizable features — the surface is so coarsely textured that it feels like sandpaper to the touch. A small to medium-sized deciduous tree reaching 10 to 30 feet in height, Netleaf Hackberry is one of the most drought-tolerant native trees in the western United States.

Netleaf Hackberry grows naturally in rocky canyon walls, dry slopes, streamside terraces, and the margins of desert washes and watercourses from California east through the Southwest and Great Plains. It tolerates extreme heat, alkaline soils, rocky substrates, and extended drought that would kill most other trees. At the same time, it can grow in riparian zones with seasonal flooding. This extraordinary adaptability makes it one of the most useful native trees for harsh, challenging sites throughout the Intermountain West and Southwest.

Beyond its toughness, Netleaf Hackberry offers genuine ornamental qualities: attractive corky-warted bark, interesting leaf texture, small reddish-orange to dark purple berries in fall that are consumed by wildlife, and yellow to orange fall color. In areas where water is scarce and tree choices are limited, Netleaf Hackberry is an indispensable native species for shade, wildlife habitat, and erosion control.

Identification

Netleaf Hackberry grows as a small to medium-sized deciduous tree reaching 10 to 30 feet (3–9 m) in height, with an irregular, spreading crown that becomes broad with age. Young trees often have multiple stems; mature trees typically develop a single trunk with spreading branches. The bark is one of the most distinctive identification features: grayish-brown with prominent corky, irregular warts and ridges that give it a very rough, knobby texture.

Leaves

The leaves are the feature that gives the species its common name. Each leaf is ovate to broadly lance-shaped, 1 to 3 inches (2.5–7.5 cm) long, with an asymmetric base (one side of the leaf base is attached lower on the leaf stalk than the other) — a characteristic feature of the hackberry genus. The surface is distinctly rough (scabrous) due to rough hairs on the upper surface, while the underside has prominent netted (reticulate) venation that is raised and visible. Leaf margins have irregular, coarse teeth. Fall color ranges from yellow to orange.

Flowers

The flowers are tiny and inconspicuous — greenish-yellow, about 1/8 inch across — appearing in early spring before or as the leaves emerge. They are not ornamentally significant but do provide pollen for early-season native bees. Male and female flowers are separate but occur on the same tree (monoecious), so a single tree is sufficient for fruit production.

Fruit

The fruit is a small, round drupe (berry-like) measuring ¼ to ⅜ inch (6–10 mm) in diameter. Fruits ripen from August through October, transitioning from green to reddish-orange and finally to dark purple or black at full maturity. The skin is thin; the flesh is dry and thin around a single hard seed. The fruits are sweet enough to eat directly from the tree and are consumed eagerly by birds and mammals. They persist on the tree well into winter, providing important late-season food for wildlife.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Celtis reticulata |

| Family | Cannabaceae (Hemp Family) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 10–30 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | March – May |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow (inconspicuous) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 5–9 |

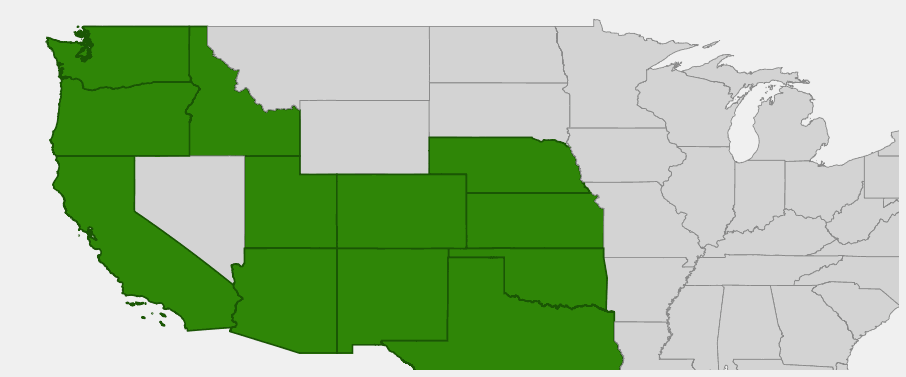

Native Range

Netleaf Hackberry is native to western North America from Oregon and Washington south through California to Baja California, east through Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska. It is most abundant and characteristic in the warm desert Southwest — Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas — where it is a common component of desert riparian corridors, canyon woodlands, and rocky bajadas. It is also found in the Intermountain West in canyon systems and dry rocky hillsides.

Within its range, Netleaf Hackberry grows most commonly in rocky, well-drained sites: cliff faces, talus slopes, canyon walls, dry rocky hillsides, and the elevated terraces above desert washes and streams. It is less common on flat valley bottoms or in areas with poor drainage. The species is well adapted to alkaline soils — a common characteristic of western soils — and often grows in association with Desert Willow (Chilopsis linearis), Velvet Ash (Fraxinus velutina), New Mexico Olive (Forestiera neomexicana), and various oak species.

Netleaf Hackberry also occurs in canyon woodlands at moderate elevations, growing alongside Gambel Oak (Quercus gambelii), One-seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma), and Pinyon Pine (Pinus edulis) in the piñon-juniper woodland zone. It is one of relatively few deciduous trees that grows in the piñon-juniper zone across much of the Southwest.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Netleaf Hackberry: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Netleaf Hackberry is one of the most stress-tolerant native trees available for xeriscape and dry-climate gardens. It thrives on neglect once established and tolerates conditions that would kill most ornamental trees.

Light

Full sun is preferred — Netleaf Hackberry grows and fruits best with maximum sun exposure. It can tolerate light shade but develops a more open, less productive form. In the hottest desert areas, it may benefit from some afternoon shade during establishment, but mature trees thrive in full desert exposure.

Soil & Water

Netleaf Hackberry is truly drought-tolerant and actually prefers dry, well-drained, rocky, or sandy soils. It grows in alkaline soils that are inhospitable to most trees and can handle the calcareous, rocky soils common throughout the Southwest. In established landscapes, it requires little to no supplemental irrigation once established — typically just deep watering 2–3 times in summer during prolonged drought in its first 2–3 years. Do not plant in wet, poorly-drained soil, which will cause root rot.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring or fall from container stock. Dig a wide, shallow hole in native soil without amendment. Set the tree so the root flare is at or slightly above the soil surface — elevated planting helps drainage around the crown. Stake temporarily if needed in windy sites. Apply a ring of gravel mulch to reflect heat and keep the crown dry. Avoid organic mulch directly against the trunk.

Pruning & Maintenance

Netleaf Hackberry requires minimal pruning. Remove dead or damaged branches and any crossing branches in late winter. Young trees may need selective pruning to develop a strong central leader, but mature trees typically develop an attractive irregular form on their own. The tree is naturally resistant to most pests and diseases, though it can be affected by hackberry nipple gall (a cosmetic pest that produces small bumps on leaves) and occasionally by witches’ broom — neither is harmful to the tree’s health.

Landscape Uses

- Shade tree for xeric landscapes where other trees won’t grow

- Canyon and rock garden specimen — spectacular in rocky, natural settings

- Wildlife habitat — berries feed many bird species through winter

- Erosion control on dry rocky slopes and canyon walls

- Riparian restoration in desert wash habitats

- Street tree in arid cities and towns — handles compacted, alkaline urban soils

- Windbreak in hot, dry sites where other trees fail

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Netleaf Hackberry is among the most wildlife-productive native trees in the arid West, providing food, shelter, and nesting habitat for a remarkable diversity of species across multiple seasons.

For Birds

The persistent berries are consumed through fall and winter by Northern Flickers, American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Yellow-rumped Warblers, Western Bluebirds, Phainopepla, and dozens of other fruit-eating species. The dense, irregular branching provides excellent nesting sites for raptors — Cooper’s Hawks and Red-tailed Hawks commonly nest in larger hackberry trees. The bark harbors insect larvae that woodpeckers exploit. In the Southwest, Hackberry Emperor butterflies (Asterocampa celtis) depend on hackberry species as their sole larval host plant.

For Mammals

The sweet berries are eaten by coyotes, foxes, raccoons, skunks, ringtails, and various rodents. Deer browse the foliage, particularly in drought years. The tree also supports Hackberry Emperor and Question Mark butterfly caterpillars, which in turn feed insectivorous bats. In the Southwest, mountain lions occasionally rest in the branches of large hackberry trees in canyon habitat.

For Pollinators

The inconspicuous flowers are wind-pollinated but provide some pollen for very early-season native bees. More significantly, Netleaf Hackberry is the host plant for Hackberry Emperor (Asterocampa celtis), American Snout (Libytheana carinenta), and Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) butterflies — making it a critical larval food plant supporting butterfly populations throughout the arid West.

Ecosystem Role

In canyon and desert wash ecosystems, Netleaf Hackberry is a keystone species — often the only shade tree on rocky slopes and canyon walls where no other large deciduous tree can survive. Its shade moderates air and soil temperature beneath the canopy, creating a cooler microhabitat that shelters numerous other species. The berries, persisting through winter, provide a critical food resource during the period when other fruits are gone. The tree’s ability to grow on vertical cliff faces and unstable talus makes it irreplaceable in these unique habitats.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Netleaf Hackberry berries were an important food source for numerous Indigenous peoples of the Southwest and Great Plains, including the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, and various Apache groups. The small, sweet berries were eaten fresh, dried for storage, or ground into a paste that could be mixed with fat and dried meat. The Zuni dried the berries and ground them with seeds to make a sweet, calorie-rich food that could be carried as trail food — an important consideration in the demanding desert environment. Some groups also used the berries to flavor and preserve other foods.

The wood of Netleaf Hackberry is hard, heavy, and flexible — qualities that made it valuable for making bows, arrows, and tool handles in traditions across its range. The Navajo used the wood for ceremonial purposes and the bark for medicinal preparations. The tough, flexible branches were used in basket-making and for weaving material in some traditions. Because the tree was one of relatively few that grew in certain canyon and desert environments, it held particular importance as a resource in areas where wood was scarce.

Modern uses of Netleaf Hackberry are primarily ecological and landscaping-focused. The tree is increasingly planted in southwestern cities and towns as a drought-tolerant, wildlife-friendly shade tree for urban landscapes, parks, and highway plantings. It is featured in numerous xeriscape and water-wise gardening demonstrations across the Southwest, and its role as a butterfly host plant has attracted growing interest from habitat gardeners.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Netleaf Hackberry berries edible?

Yes — the ripe berries (dark purple-black when fully mature) are sweet and edible directly from the tree. They have a date-like, somewhat dry sweetness and contain a large seed relative to the thin layer of fruit flesh. They have been a food source for both Indigenous peoples and wildlife for thousands of years.

Why do my hackberry leaves have bumps on them?

The small round bumps on hackberry leaves are hackberry nipple galls — created by tiny psyllid insects (Pachypsylla spp.) that cause the leaf tissue to grow around them as a protective structure. The galls are cosmetically unappealing but are harmless to the tree. No treatment is needed or recommended.

How fast does Netleaf Hackberry grow?

Growth rate is moderate — typically 1 to 2 feet per year under good conditions. In drier sites with less water, growth is slower but the tree remains healthy. It can reach 15–20 feet within 10–15 years of planting and will eventually reach 25–30 feet with adequate time.

Is Netleaf Hackberry the same as Common Hackberry?

No — Celtis reticulata (Netleaf Hackberry) is a western species adapted to arid conditions, while Celtis occidentalis (Common Hackberry) is an eastern species of moist bottomlands and woodlands. Netleaf Hackberry can be distinguished by its smaller, rougher, more strongly netted leaves, smaller size, and preference for dry rocky sites.

Can Netleaf Hackberry grow in heavy clay soil?

Netleaf Hackberry is more tolerant of varied soils than many desert trees, but heavy, poorly-draining clay is not ideal. It prefers rocky, sandy, or gravelly soils with good drainage. In clay soils, ensure that water drains away from the root zone after rain or irrigation — standing water causes root rot in hackberry as in most desert trees.