Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Diospyros virginiana, commonly known as American Persimmon or simply Persimmon, is one of North America’s most distinctive and ecologically valuable native fruit trees. This member of the Ebenaceae (ebony) family produces the continent’s largest edible native fruit — sweet, custard-like persimmons that have sustained both wildlife and human populations for millennia. Found throughout much of the eastern and central United States, this adaptable deciduous tree can reach heights of 30 to 50 feet with a distinctive checkered bark pattern and glossy, dark green leaves that transform into brilliant shades of yellow, orange, and mauve each autumn.

The American Persimmon is perhaps best known for its remarkable fruit — orange, globe-shaped persimmons about 1 to 2 inches in diameter that ripen in fall after the first frost. When fully ripe, these fruits are incredibly sweet and custard-like in texture, but unripe persimmons contain high levels of tannins that create an intensely astringent, mouth-puckering sensation. This natural defense mechanism protects the developing seeds until they’re fully mature and ready for dispersal by wildlife. The tree is dioecious, with separate male and female trees, and only the females produce fruit when pollinated by nearby males.

Beyond its value as a food source, American Persimmon serves as a crucial larval host plant for several butterfly species and supports a wide range of wildlife throughout the year. Its tolerance for diverse growing conditions — from full sun to full shade, and from dry uplands to moist bottomlands — makes it exceptionally adaptable to various landscape situations. The tree’s deep taproot and drought tolerance make it valuable for challenging sites, while its wildlife benefits and stunning fall color create four-season garden interest that few other native trees can match.

Identification

American Persimmon is easily identified by its distinctive bark, glossy leaves, and unique fruit characteristics. The tree typically develops a narrow, upright crown with a straight central trunk.

Bark

The most distinctive identifying feature is the bark, which develops a characteristic “alligator hide” or checkered pattern on mature trees. The bark is dark gray to black, broken into small, thick, square-shaped blocks that create a distinctive mosaic pattern. Young trees have smoother, grayish bark that gradually develops the characteristic blocky pattern as the tree matures. This distinctive bark pattern makes persimmon trees easily recognizable even from a distance during winter months.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and oval-shaped, typically 3 to 6 inches long and 2 to 3 inches wide. They have smooth, untoothed margins and a distinctive glossy, dark green upper surface that catches light beautifully. The underside is paler green and may be slightly pubescent (fuzzy) when young. Leaf venation is pinnate with prominent lateral veins. In autumn, the foliage creates a spectacular display, turning brilliant shades of yellow, orange, red, and mauve — often showing multiple colors simultaneously on a single tree.

Flowers & Fruit

American Persimmon is dioecious, with male and female flowers on separate trees. Male flowers are small, yellowish-white, and appear in clusters along the branches in late spring. Female flowers are larger, cream-colored, and typically solitary or in small groups. Both types of flowers have a waxy appearance and subtle fragrance that attracts various pollinators.

The fruit is the tree’s most celebrated feature — a large, globe-shaped berry 1 to 2.5 inches in diameter, with smooth, thin skin that ranges from yellow-orange to deep orange or reddish-orange when ripe. The flesh is sweet, custardy, and extremely rich when fully ripe, but intensely astringent and unpalatable before full ripeness. Fruits typically ripen in September through November after the first frost, with the timing varying by location and weather conditions.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Diospyros virginiana |

| Family | Ebenaceae (Ebony) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Fruit Tree |

| Mature Height | 30–50 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | Yellowish-white to cream |

| Fruit | Large orange berries (female trees only) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–9 |

Native Range

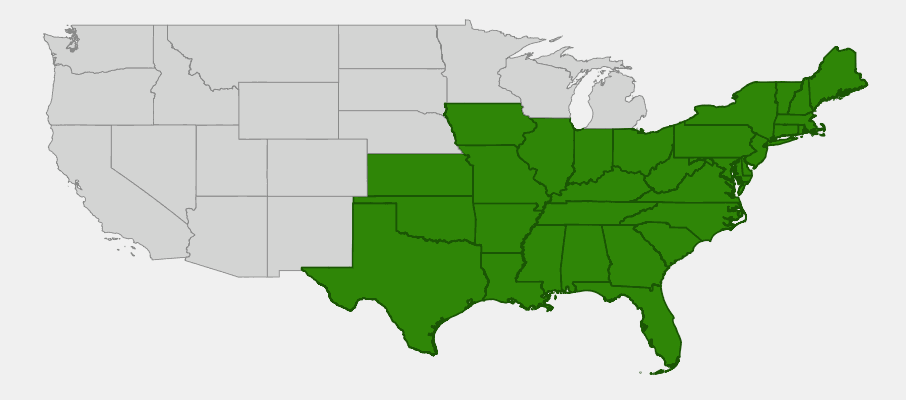

American Persimmon has one of the broadest native ranges of any North American fruit tree, extending from southern New England and New York south to Florida, and west to eastern Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. This extensive distribution reflects the species’ remarkable adaptability to diverse climates and growing conditions. The tree is found from sea level in coastal areas to elevations of 2,000 feet or more in mountainous regions, though it is most common in the eastern deciduous forests and Great Plains border regions.

Throughout its range, persimmon inhabits a variety of habitats including river bottomlands, forest edges, old fields, fence rows, and disturbed areas. The species shows particular tolerance for poor, dry soils and is often found on sites where other trees struggle to establish. In bottomland areas, persimmon grows alongside other flood-tolerant species like Green Ash and Cottonwood, while on drier upland sites it associates with oaks, hickories, and other drought-adapted species.

The northernmost populations of American Persimmon are found in southern New England and the Great Lakes region, where the trees are somewhat smaller and the fruit often requires a longer growing season to fully ripen. Southern populations, particularly in the Gulf Coastal Plain, can produce larger trees and more abundant fruit crops with longer ripening seasons extending well into winter.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring American Persimmon: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

American Persimmon is one of the most adaptable and low-maintenance native trees, capable of thriving in a wide range of conditions once established. Understanding its growth habits and preferences will ensure success in cultivation.

Light

One of persimmon’s greatest strengths is its exceptional adaptability to different light conditions. The tree grows well in full sun, partial shade, and even fairly dense shade, though fruit production is best in full sun to light shade. In deep shade, trees may become more spindly and produce fewer or no fruit, but will still provide valuable wildlife habitat and attractive foliage. This flexibility makes persimmon excellent for challenging sites where light levels vary throughout the day.

Soil & Water

American Persimmon is remarkably tolerant of poor soils and drought conditions, thanks to its deep taproot system. The tree grows well in sandy, loamy, or clay soils and tolerates both acidic and slightly alkaline conditions (pH 4.5-8.0). While drought tolerant once established, consistent moisture during the first few years and during fruit development will improve growth and fruit production. Avoid areas with standing water or extremely wet conditions, as persimmons prefer well-drained sites.

Planting Tips

Plant American Persimmon in spring or fall, choosing a location with adequate space for the mature tree size. If fruit production is desired, plant both male and female trees — typically one male for every 6-8 females within 100-200 feet. Young trees develop a deep taproot quickly, so transplant nursery stock while still small (under 4 feet tall) for best success. Avoid disturbing the root system during planting, as persimmons resent root disturbance.

Pruning & Maintenance

American Persimmon requires minimal pruning and naturally develops an attractive upright form. Prune only to remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches, ideally during dormancy. Young trees may benefit from some training to establish a strong central leader. The tree is naturally pest and disease resistant, requiring no routine treatments. Established trees are extremely drought tolerant but may drop fruit during severe dry spells.

Landscape Uses

American Persimmon excels in numerous landscape applications:

- Wildlife gardens — exceptional value for birds and butterflies

- Naturalized areas — perfect for forest edges and meadow plantings

- Edible landscapes — provides delicious fall fruit

- Difficult sites — tolerates poor soils and drought

- Shade trees — medium-sized canopy with attractive form

- Fall color displays — brilliant autumn foliage

- Erosion control — deep roots stabilize slopes

- Restoration projects — supports native ecosystem recovery

Wildlife & Ecological Value

American Persimmon provides exceptional wildlife value throughout the year, supporting everything from tiny butterflies to large mammals, making it one of the most ecologically important trees in its native range.

For Birds

The large, sweet fruits are consumed by over 20 species of birds, including Wild Turkeys, Bobwhite Quail, American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Blue Jays, and various woodpecker species. The fruits are particularly important during fall migration when high-energy foods are crucial for long-distance travelers. The tree’s branching structure provides excellent nesting sites for medium-sized birds, while the flowers attract insects that serve as important protein sources during the breeding season.

For Mammals

Persimmon fruits are eagerly consumed by numerous mammals including White-tailed Deer, Black Bears, Raccoons, Opossums, Foxes, and Squirrels. The high sugar content makes them an important fall food source for animals preparing for winter. Small mammals also consume fallen fruits throughout the winter months when other foods are scarce. The bark and twigs may be browsed by deer during times of food shortage.

For Butterflies

American Persimmon serves as a larval host plant for several butterfly species, most notably the Luna Moth and various sphinx moths. The Gray Hairstreak butterfly also uses persimmon as a host plant. The spring flowers provide nectar for early-season butterflies and other pollinators when few other flowers are available. This dual role as both host plant and nectar source makes persimmon particularly valuable in butterfly conservation.

Ecosystem Role

Persimmon plays a crucial role in forest succession and ecosystem dynamics. Its ability to establish in disturbed areas and poor soils makes it an important pioneer species that helps stabilize sites and facilitate the establishment of other plants. The deep taproot brings nutrients from lower soil layers to the surface through leaf drop, improving soil fertility for surrounding vegetation. The tree’s longevity and fruit production create reliable food resources that many wildlife species depend on year after year.

Cultural & Historical Uses

American Persimmon holds a rich place in North American cultural and culinary history, with Indigenous peoples incorporating the fruit into their diets and traditional practices for thousands of years. Numerous tribal nations throughout the tree’s range developed sophisticated methods for harvesting, processing, and preserving persimmons. The Cherokee, Creek, and other southeastern tribes dried persimmons to create concentrated cakes that could be stored for months, providing crucial winter nutrition. These dried persimmon cakes were often mixed with cornmeal or used to sweeten other foods.

The astringent properties of unripe persimmons were well understood by Indigenous peoples, who developed techniques for removing tannins through repeated leaching or waiting for full ripeness after frost. Some tribes used persimmon wood for specialized tools and implements, taking advantage of the extremely hard, dense heartwood that characterizes the ebony family. The inner bark was used medicinally for treating various ailments including digestive issues and sore throats.

European colonists quickly learned about persimmons from Native Americans and incorporated the fruit into their own diets and traditions. Early American settlers used persimmons to make beer, wine, and brandy, while the seeds were roasted as a coffee substitute during times of scarcity, including the Civil War era. Persimmon wood became prized for specialty applications requiring extremely hard, smooth wood — most famously for golf club heads and textile shuttle blocks in early American manufacturing.

In modern times, American persimmons have experienced a renaissance among foragers, sustainable food enthusiasts, and native plant gardeners. The fruit is increasingly featured at farmers markets and specialty food stores, while chefs have rediscovered its unique flavor for desserts, baked goods, and traditional foods. Contemporary breeding programs have developed improved cultivars with larger fruit and better flavor, though many enthusiasts prefer the intense sweetness and complex flavors of wild persimmons. The tree’s ecological importance has also been recognized in restoration and conservation efforts throughout its native range.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell when persimmons are ripe enough to eat?

Ripe persimmons are very soft to the touch — almost squishy — and fall naturally from the tree or come off with gentle pressure. The skin should be deep orange and may appear slightly wrinkled. Any firmness indicates the fruit is still astringent. Generally, wait until after the first frost for best eating quality.

Why are some persimmons incredibly astringent while others are sweet?

Unripe persimmons contain high levels of water-soluble tannins that create the mouth-puckering sensation. As the fruit fully ripens, these tannins become bound to proteins and are no longer astringent. Full ripeness is essential — even slightly underripe fruit can be unpalatable.

Do I need both male and female trees to get fruit?

Yes, American Persimmon is dioecious and requires cross-pollination between separate male and female trees. You cannot determine sex until trees begin flowering, typically at 5-10 years of age. Plant multiple trees to increase odds of having both sexes, or purchase sexed trees from specialty nurseries.

How long does it take for persimmon trees to produce fruit?

Trees grown from seed typically begin producing fruit at 8-15 years of age, while grafted varieties may fruit in 3-5 years. Production increases with tree maturity, with peak production often not reached until trees are 25-30 years old.

Can I grow American Persimmon outside its native range?

American Persimmon adapts well to cultivation throughout USDA zones 4-9, including areas outside its native range. The tree is particularly successful in the Pacific Northwest and parts of the Southwest where irrigation is available. However, fruit ripening may be inconsistent in areas with short growing seasons.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries American Persimmon?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina