Winterberry Holly (Ilex verticillata)

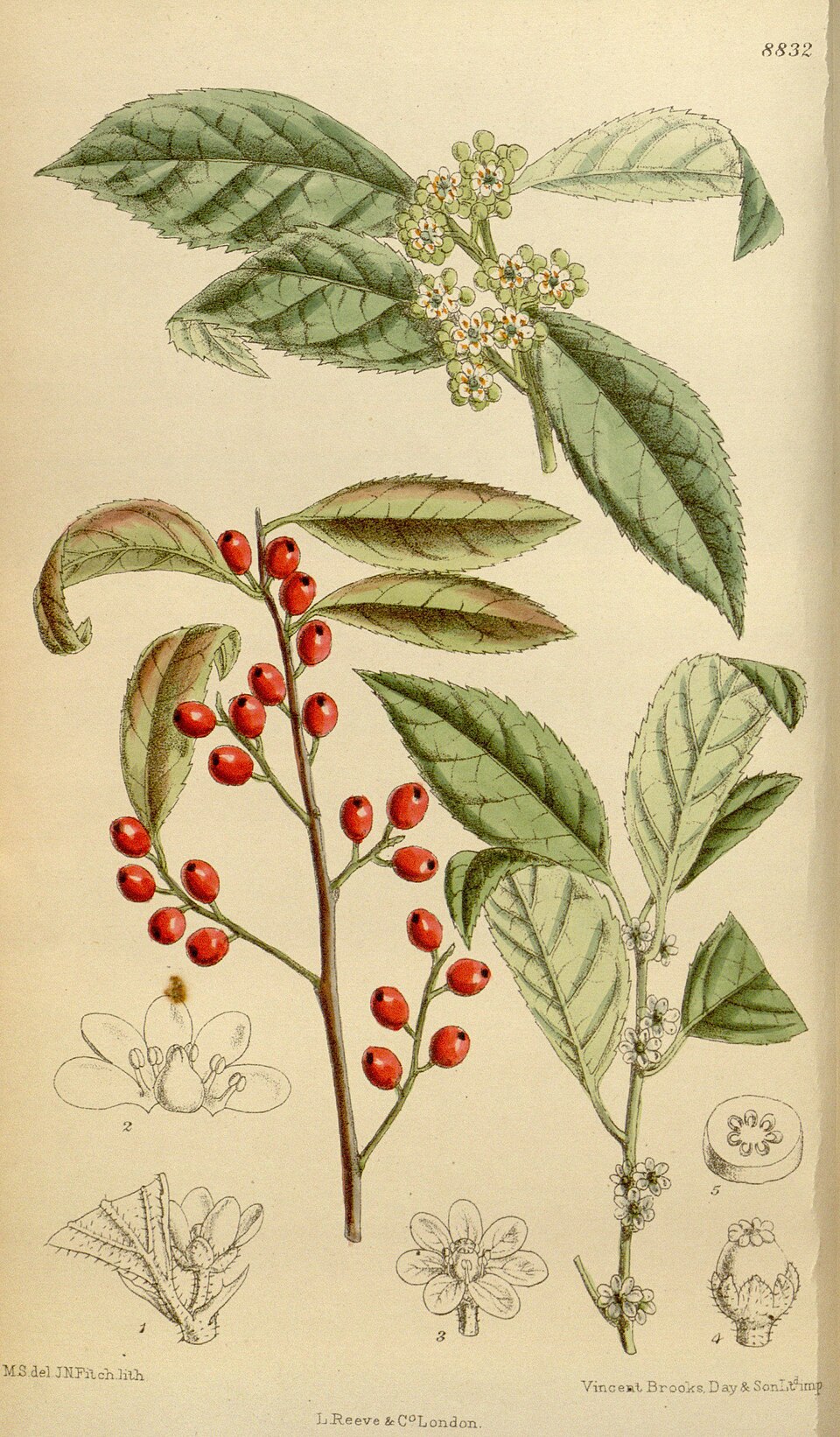

Ilex verticillata, commonly known as Winterberry Holly, Common Winterberry, or Black Alder, is one of North America’s most spectacular native shrubs for winter interest. This deciduous member of the holly family (Aquifoliaceae) defies the typical evergreen holly stereotype, dropping its leaves in autumn to reveal branches laden with brilliant red berries that persist throughout the winter months, creating some of the most striking displays in the dormant season landscape.

Growing 6 to 10 feet tall (and occasionally up to 15 feet), Winterberry Holly forms a multi-stemmed, upright shrub with an irregular, somewhat open crown. The magic happens after the leaves fall — thousands of bright red berries cluster along the branches, creating what appears to be a shrub made of tiny red jewels against the stark winter landscape. This remarkable display can last from November through March, providing crucial food for wildlife when other sources are scarce and creating unparalleled ornamental value in the garden.

Native to wetland areas across much of eastern North America, Winterberry Holly thrives in consistently moist to wet soils, making it an excellent choice for rain gardens, pond edges, and low-lying areas where many other shrubs struggle. Its adaptability to both sun and partial shade, combined with its exceptional wildlife value and stunning winter display, makes it a cornerstone species for native plant gardens, wildlife habitats, and naturalized landscapes throughout its extensive range.

Identification

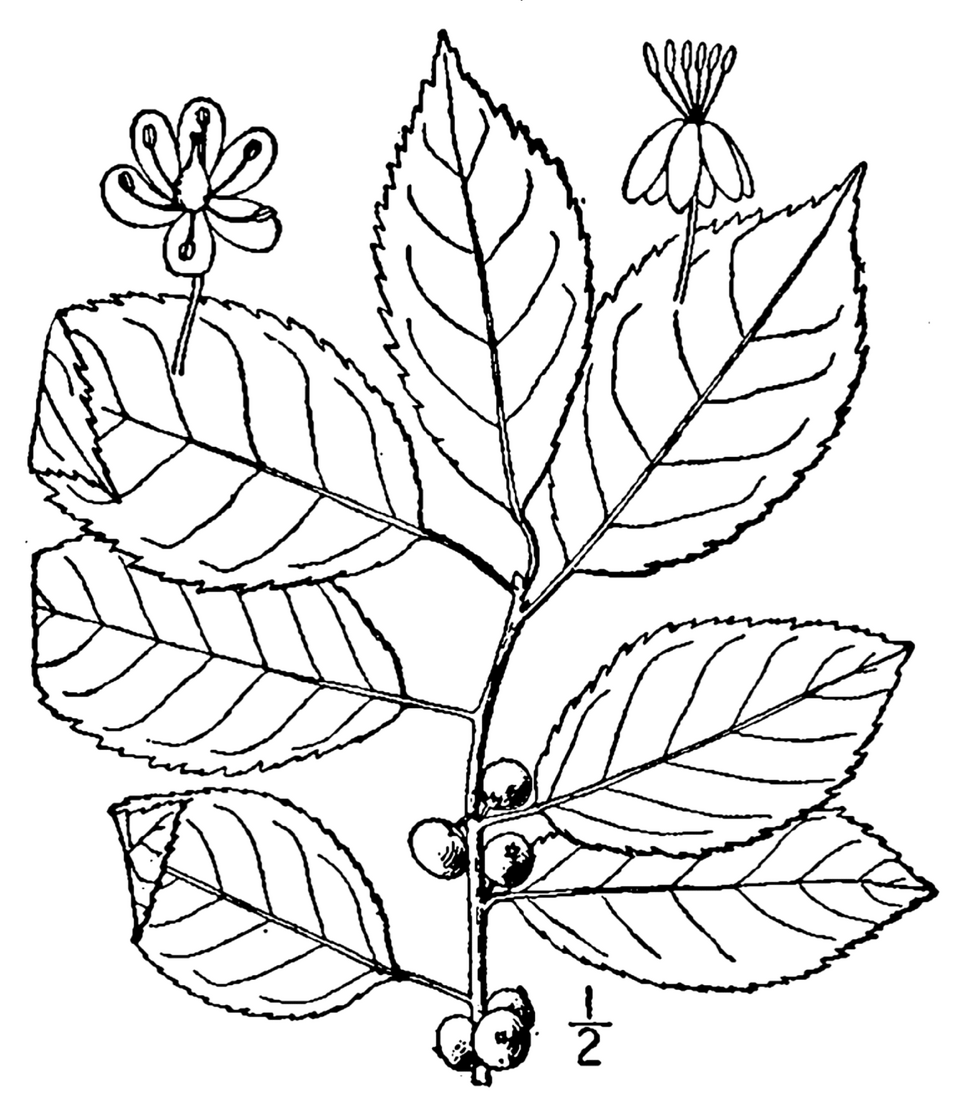

Winterberry Holly is a deciduous shrub that typically grows 6 to 10 feet tall with an equal spread, though it can reach up to 15 feet under optimal conditions. Unlike most holly species, it completely loses its leaves in autumn, making the berry display even more dramatic against the bare branches. The shrub forms multiple stems from the base, creating a naturally rounded to somewhat irregular form.

Bark

The bark is smooth and grayish-brown when young, becoming slightly rougher with age but retaining its relatively smooth texture throughout the plant’s life. Young twigs are green to reddish-brown and smooth, turning gray-brown as they mature. The winter silhouette is characterized by numerous ascending branches that create an open, somewhat sparse appearance when not in berry.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and elliptical to obovate, measuring 1½ to 4 inches long and ¾ to 2 inches wide. They have a distinctive appearance with serrated margins and prominent veining, dark green above and paler beneath. The leaf surface is somewhat dull rather than glossy, helping to distinguish Winterberry from evergreen hollies. In autumn, the foliage typically turns yellow before dropping, though fall color is generally not considered ornamental.

Flowers

Winterberry Holly is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers appear on separate plants. Both flower types are small, about ¼ inch across, and greenish-white in color. Female flowers appear in small clusters of 1 to 3 blooms in the leaf axils, while male flowers occur in more numerous clusters of 3 to 12. The flowers bloom in late spring to early summer (May to July) and are attractive to small bees and beneficial insects, though they’re not particularly showy.

Fruit

The fruit is the shrub’s crowning glory — brilliant red berries (drupes) about ¼ to ⅜ inch in diameter that develop in dense clusters along the branches. Each berry contains 3 to 5 hard seeds (nutlets). The berries begin forming in late summer, ripen to bright red in early fall, and persist through winter until consumed by birds or weather-damaged. Only female plants produce berries, and they require a male plant nearby for pollination.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Ilex verticillata |

| Family | Aquifoliaceae (Holly) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 6–10 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | May – July |

| Flower Color | Greenish-white |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

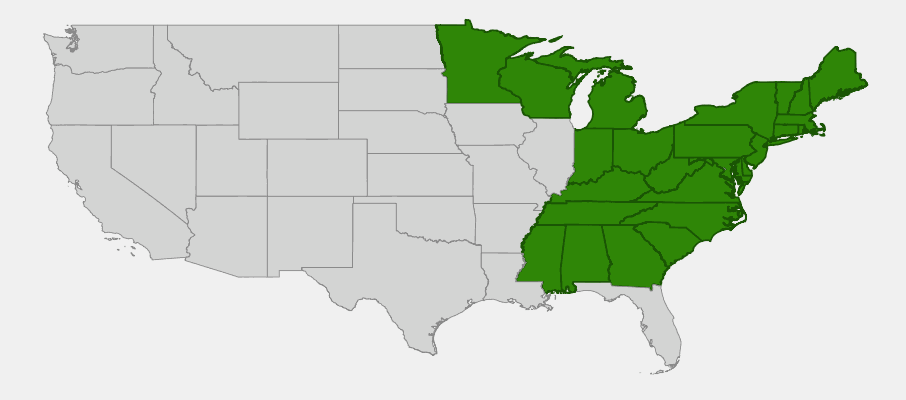

Native Range

Winterberry Holly has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American holly species, stretching from Canada south to the Gulf Coast and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Great Plains. This remarkable distribution reflects the species’ exceptional adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and its specialization in wetland habitats that occur throughout much of the continent.

In its natural habitat, Winterberry Holly is typically found in wetland areas including swamps, marshes, pond edges, stream banks, and seasonally wet areas. It thrives in the moist to wet soils of these habitats, often growing in association with other wetland plants like Red Maple, Black Gum, Swamp Azalea, and various sedges and ferns. The species is particularly common in areas with fluctuating water levels, showing remarkable tolerance for both temporary flooding and seasonal drying.

From the pine barrens of New Jersey to the cypress swamps of the Southeast, from the Great Lakes region to the wetlands of eastern Texas, Winterberry Holly has adapted to a wide variety of wetland types across its range. This broad ecological tolerance has made it one of the most reliable and widely distributed native shrubs for wetland restoration and rain garden applications throughout much of North America.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Winterberry Holly: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

Winterberry Holly is remarkably easy to grow when its basic needs are met, particularly its requirement for consistent moisture. Once established, it requires minimal care while providing exceptional ornamental value and wildlife benefits.

Light

Winterberry Holly performs best in full sun to partial shade, with at least 4–6 hours of direct sunlight for optimal berry production. In full sun, plants develop denser growth and produce more abundant berries, while in partial shade they tend to be more open and may have reduced fruiting. The species tolerates fairly deep shade but flowering and berry production will be significantly diminished in heavily shaded locations.

Soil & Water

This is where Winterberry Holly truly shines — it thrives in consistently moist to wet soils that would be problematic for many other shrubs. It prefers slightly acidic soils (pH 4.5–6.5) but adapts to neutral conditions. The shrub can tolerate seasonal flooding and is excellent for areas with poor drainage, rain gardens, and pond edges. While it requires consistent moisture, established plants can tolerate brief dry periods, though berry production may be reduced.

Planting Tips

Plant Winterberry Holly in spring or fall, spacing plants 6–8 feet apart for mass plantings or specimen use. For berry production, plant at least one male plant for every 6–8 female plants within 50 feet of each other. Popular male cultivars include ‘Jim Dandy’ and ‘Southern Gentleman,’ while female cultivars like ‘Winter Red’ and ‘Red Sprite’ offer exceptional berry displays. Choose locations where the winter berry display can be appreciated from indoors.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal pruning is required, though light pruning in late winter or early spring can help maintain shape and encourage bushier growth. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches as needed. Avoid heavy pruning as this can reduce flowering and berry production. The shrub may produce suckers from the base, which can be removed if a more formal appearance is desired or left to create natural colonies.

Landscape Uses

Winterberry Holly’s unique characteristics make it valuable in specialized landscape applications:

- Rain gardens and bioretention areas — excellent for managing stormwater

- Pond and stream edges — thrives in consistently moist soils

- Wildlife gardens — essential for winter bird feeding

- Winter interest gardens — provides spectacular cold-season display

- Wetland restoration — important native species for habitat creation

- Foundation plantings where soil stays moist

- Cut branch arrangements — branches with berries are prized for holiday decorating

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Winterberry Holly is one of the most important native shrubs for wildlife, particularly during the challenging winter months when food sources are scarce.

For Birds

The berries are consumed by over 40 species of birds, making Winterberry Holly a critical component of winter survival for many species. Key consumers include American Robins (which often form large flocks to feed on the berries), Cedar Waxwings, Northern Cardinals, Blue Jays, and various sparrows. The timing is crucial — the berries persist from November through March, providing essential nutrition during the coldest months when insects and other food sources are unavailable.

For Other Wildlife

Small mammals including chipmunks and squirrels occasionally consume the berries, though they’re not a preferred food source. White-tailed deer may browse the foliage, particularly in winter, though the plant usually recovers well from moderate browsing. The dense branching structure provides nesting sites and protective cover for small birds and mammals throughout the year.

For Pollinators

While the flowers are small and not particularly showy, they’re valuable to specialized pollinators including small native bees, flies, and beneficial wasps. The male plants are particularly important as they produce abundant pollen, while female plants provide nectar. The blooming period fills an important gap in early summer when many spring flowers have finished but summer bloomers haven’t yet started.

Ecosystem Role

As a native wetland specialist, Winterberry Holly plays a crucial role in wetland ecosystems. It helps stabilize soil along water edges, provides habitat structure, and supports complex food webs. The shrub is particularly valuable in fragmented landscapes, providing stepping-stone habitat that allows wildlife to move between larger habitat patches. Its extended berry display makes it a reliable food source that birds can depend on year after year.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Winterberry Holly has been valued by Indigenous peoples throughout its range for both practical and medicinal uses. Many tribes, including the Cherokee, Iroquois, and various Algonquin groups, recognized the plant’s properties and incorporated it into their traditional practices. The inner bark was used medicinally to treat various ailments including fevers, coughs, and skin conditions, while the berries served as emergency food during harsh winters, though they required processing to be palatable.

The common name “Black Alder” reflects early European settlers’ recognition of the plant’s similarity to the European Black Alder (Alnus glutinosa), though the two species are unrelated. Settlers learned about the plant’s uses from Indigenous peoples and incorporated it into their own folk medicine traditions. The bark was sometimes used as a substitute for quinine in treating fevers, and various plant parts were employed in home remedies for digestive and respiratory ailments.

In more recent history, Winterberry Holly has gained tremendous popularity in the horticultural trade, particularly for its exceptional winter ornamental value. The cutting of berry-laden branches for holiday decorating has become a significant industry in some areas, with managed cutting operations providing sustainable harvest of this beautiful native plant. Many cultivars have been developed to enhance berry size, color, and persistence, making Winterberry Holly one of the most important native shrubs in the nursery trade.

The species has also become a symbol of native plant gardening and ecological landscaping, representing the principle that native plants can provide both exceptional beauty and important ecological functions. Its use in rain gardens and bioretention systems has made it an ambassador species for environmentally conscious landscaping, demonstrating how native plants can solve practical problems while supporting wildlife and creating beautiful gardens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why isn’t my Winterberry Holly producing berries?

The most common reason is lack of a male plant for pollination. Winterberry Holly is dioecious, meaning you need both male and female plants to get berries. Make sure you have a male plant within 50 feet of female plants. Other causes include too much shade, poor growing conditions, or the plant being too young (may take 3–5 years to reach fruiting maturity).

Can I eat Winterberry Holly berries?

The berries are technically edible but are quite bitter and astringent, and they can cause digestive upset if eaten in quantity. They’re much better left for the birds, which have evolved to process them safely. The berries are an important winter food source for wildlife and should not be harvested for human consumption.

When should I prune my Winterberry Holly?

Prune in late winter or very early spring before new growth begins, if pruning is necessary at all. Light pruning to remove dead or crossing branches is usually sufficient. Avoid heavy pruning as this can reduce flowering and berry production. If you’re harvesting branches for holiday decorating, this provides natural pruning.

Will Winterberry Holly grow in regular garden soil?

While Winterberry Holly prefers consistently moist to wet soils, it can adapt to regular garden soil if it receives adequate water, particularly during dry periods. However, it will never perform as well as in its preferred wetland conditions. For best results, choose sites with naturally moist soil or supplemental irrigation.

How can I tell male and female plants apart?

Male and female plants look very similar until they flower. Male flowers occur in larger, more numerous clusters (3–12 per cluster) while female flowers appear in smaller groups of 1–3. Obviously, only female plants produce berries. Many nurseries label plants by sex or sell them as matched pairs to ensure proper pollination.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Winterberry Holly?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina