Prince’s Plume (Stanleya pinnata)

Stanleya pinnata, commonly known as Prince’s Plume or Desert Plume, is one of the most dramatic and visually striking wildflowers of the American West. A member of the Brassicaceae (mustard) family, this robust, somewhat woody perennial sends up towering spikes of lacy, sulfur-yellow flowers from spring through summer, creating a spectacular display in dry desert and semi-desert landscapes. Named for Lord Edward Stanley, a 19th-century English naturalist and ornithologist, Prince’s Plume has a commanding presence that belies the harsh, selenium-rich desert soils where it grows.

Prince’s Plume is most notable as a selenium hyperaccumulator — one of only a handful of plant species in North America that concentrates selenium (a toxic element) from the soil in its tissues at levels hundreds of times greater than surrounding vegetation. This unusual ability makes Prince’s Plume both a bioindicator of selenium-rich soils (useful to botanists and geologists) and an important component of selenium cycling in western desert ecosystems. The plant is toxic to livestock and certain other animals, but its bright flowers are eagerly visited by native bees, butterflies, and other pollinators.

For native plant gardeners, Prince’s Plume is an outstanding choice for hot, dry, full-sun sites in the Intermountain West. Its long bloom season (spring through summer), bold architectural form, excellent drought tolerance, and value to pollinators make it a standout specimen or mass planting. It is tolerant of poor, rocky, and selenium-rich soils and requires minimal care once established. Few native wildflowers make a stronger statement in the dry western garden.

Identification

Prince’s Plume grows as a clump-forming, somewhat woody-based perennial, typically 3 to 4 feet (90–120 cm) tall during bloom, occasionally reaching 5 to 6 feet in favorable conditions. The plant has a bold, architectural presence — a basal rosette of large, pinnately lobed leaves from which emerge one or more tall, leafy flower spikes in spring. The overall appearance is that of a robust, yellow-flowered desert shrub when in bloom.

Leaves

The basal leaves are large — up to 8 inches (20 cm) long — and deeply pinnately lobed, with a smooth to slightly waxy texture and a blue-green color. They are distinctly asymmetric, with lobes of varying sizes along the midrib. Upper stem leaves become smaller and simpler as they ascend the flower stalk. The foliage has a somewhat unpleasant smell when crushed, due to volatile selenium compounds. The blue-green color is an adaptation for reflecting excess solar radiation in desert environments.

Flowers

The flowers are the defining feature: hundreds of small, bright sulfur-yellow, four-petaled flowers in the classic mustard family arrangement, covering long, dense terminal racemes that elongate progressively from the base upward during the long bloom period. Each flower has four long, distinctive stamens that project well beyond the petals, giving the flower spike a lacy, feathery appearance — hence the name “plume.” Flowering occurs from April through July or later at higher elevations, providing weeks of bloom.

Fruit

The fruit is a long, slender silique (a seed pod characteristic of the mustard family), 2 to 3 inches (5–7 cm) long, hanging on a curved stalk. The pods dry and split to release numerous small seeds. The drooping, pendulous pods give the post-bloom plant an interesting texture in the landscape.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Stanleya pinnata |

| Family | Brassicaceae (Mustard) |

| Plant Type | Woody-based Perennial / Sub-shrub |

| Mature Height | 3–4 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low (Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | April – July |

| Flower Color | Bright sulfur-yellow |

| Special Feature | Selenium hyperaccumulator; bioindicator of selenium soils |

| Wildlife Value | High — native bees, butterflies, selenium-adapted insects |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–9 |

Native Range

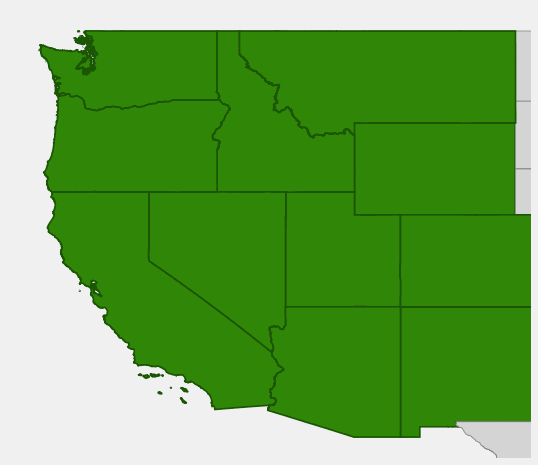

Prince’s Plume is native to the arid and semi-arid regions of western North America, ranging from the Columbia Plateau and Snake River Plain of Idaho and Oregon south through Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Arizona, New Mexico, and into Texas. It is most common in the Great Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Chihuahuan Desert regions at elevations from 2,000 to 7,500 feet. The species has a strong affinity for selenium-rich soils derived from Cretaceous marine shales, and its presence is often a reliable indicator of these soils.

In the wild, Prince’s Plume grows in open desert shrubland, dry rocky slopes, and the edges of pinyon-juniper woodland, typically on soils derived from Mancos Shale, Green River Formation, or other selenium-bearing geologic units. It is commonly found growing with Big Sagebrush, Shadscale, Four-Wing Saltbush, and various desert forbs. The plant is a pioneer on disturbed, selenium-rich soils and is often conspicuous along roadsides and on recently exposed shale slopes.

The selenium hyperaccumulation ability of Prince’s Plume is ecologically significant: by concentrating selenium from the soil and returning it to the surface through leaf litter, the plant plays a role in selenium cycling in desert ecosystems. Some specialized insects, including the selenium-accumulating beetle Baris subsimilis and certain moth larvae, have evolved to feed specifically on selenium-rich plants including Prince’s Plume — these insects themselves accumulate selenium and may play a role in transferring it to higher trophic levels.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Prince’s Plume: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Prince’s Plume is a bold, low-maintenance perennial for hot, dry, full-sun gardens in the Intermountain West. While its association with selenium-rich soils might suggest it needs special conditions, it grows well in typical sandy or gravelly dry soils without added selenium — it simply tolerates selenium where other plants cannot.

Light

Full sun is essential. Prince’s Plume is a desert plant that requires maximum sun exposure. In anything less than full sun (at least 6–8 hours of direct light), flowering will be reduced and the plant may become weak and short-lived. Choose the hottest, sunniest spot in your garden — the more exposed and desert-like, the better.

Soil & Water

Prince’s Plume thrives in poor, well-drained, sandy or gravelly soils. It grows naturally in the most mineral-poor, selenium-rich desert soils where other plants struggle. Rich garden soils or clay soils that hold moisture are problematic — excellent drainage is critical, especially over winter. Once established (typically after 1–2 years), Prince’s Plume is highly drought tolerant and needs no supplemental watering in its native range. During establishment, water deeply but infrequently to encourage deep root development.

Planting Tips

Plant container stock in spring. Choose the warmest, driest, most well-drained location. If your soil is heavy, amend with 40–50% coarse gravel before planting. Space plants 3–4 feet apart for a naturalistic mass planting. Prince’s Plume can also be grown from seed: sow outdoors in fall, or cold-stratify seeds for 4–6 weeks before spring sowing. Plants reseed modestly in favorable conditions.

Pruning & Maintenance

Prince’s Plume is largely self-maintaining. After flowering, you can leave the seed pods on for their textural interest and to allow self-seeding, or cut spent flower stalks back to the basal foliage. The plants die back to the woody base in winter and resprout strongly in spring. Divide clumps every 3–5 years if they become congested. Avoid fertilizing — rich soils produce lush, weak growth and shorten the plant’s life.

Landscape Uses

- Bold specimen plant — striking vertical accent in desert gardens

- Pollinator gardens — long bloom season attracts many native bee species

- Xeriscape plantings with native grasses, sagebrush, and desert perennials

- Dry slope plantings on rocky, exposed banks

- Naturalized areas on mineral-poor, well-drained soils

- Cut flower gardens — stems are attractive in arrangements

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite the toxicity of its selenium-rich tissues to many animals, Prince’s Plume plays an important and specialized ecological role in the desert shrubland community.

For Pollinators

The bright yellow flower spikes are visited by a variety of native bees, including Bumble Bees (Bombus spp.), mining bees (Andrena spp.), and Sweat Bees (Halictus spp.). The long bloom season (spring through summer) makes Prince’s Plume an important sustained nectar source in desert environments where flowering plants are sparse and bloom periods are often short. Some bee species appear to be tolerant of the low levels of selenium in nectar and pollen.

For Specialized Insects

Prince’s Plume supports a specialized community of selenium-tolerant insects, including leaf miners, gall-forming beetles, and moth larvae that have evolved to use selenium-hyperaccumulating plants as their hosts. These insects are among the few organisms capable of feeding on the selenium-rich foliage, and they represent a fascinating example of evolutionary adaptation to toxic conditions.

For Birds

While the seeds are not a major bird food source, the tall flower spikes attract Hummingbirds during the summer bloom period. Various flycatchers and warblers use the plant as a hunting perch, catching the insects that visit the flowers. The large, open structure of Prince’s Plume provides perching spots for desert birds in landscapes dominated by low shrubs.

Ecosystem Role

Prince’s Plume is one of the most important selenium-cycling plants in the American West. By concentrating selenium from deep soil horizons and returning it to the surface through leaf litter, it redistributes this element in ways that affect the entire soil ecosystem. The selenium in its tissues deters herbivory from most large mammals and insects, potentially giving neighboring plants a survival advantage by reducing competition.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Indigenous peoples of the Colorado Plateau and Great Basin had complex relationships with Prince’s Plume. The Navajo recognized it as a toxic plant and used it selectively in ceremonial contexts, including preparations that harnessed its toxicity in specific rituals. Paiute and Shoshone peoples were aware of its ability to make livestock sick and used this knowledge in managing livestock and wild game behavior near springs and watering holes.

Early European settlers in the West learned quickly that “locoweed” poisoning of horses and cattle was often associated with selenium-rich soils where plants like Prince’s Plume grew. The plant became important to 20th-century agricultural researchers studying selenium toxicosis in livestock, leading to a better understanding of selenium nutrition and toxicity in animals and humans.

In modern botany and geochemistry, Prince’s Plume is used as a bioindicator for selenium-rich Cretaceous shale deposits. Geologists mapping potential uranium and selenium deposits have used the presence of Prince’s Plume as a surface indicator of underlying mineral-rich geology. The plant has also attracted attention as a potential “phytoremediation” species — capable of extracting selenium from contaminated soils through repeated cropping and harvesting of selenium-rich biomass.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Prince’s Plume toxic?

Yes, to livestock and some other animals. Prince’s Plume accumulates selenium in its tissues at levels that can cause selenium toxicosis (alkali disease) in horses, cattle, and sheep that consume it. The plant is generally unpalatable to most livestock due to its strong smell, and poisoning is rare in well-managed grazing situations. It is not a concern for typical home gardens where livestock are not present.

Does Prince’s Plume spread aggressively?

No — it is a clump-forming perennial that spreads slowly from the base and self-seeds modestly. It is not invasive or aggressive and is easily managed in the garden. In appropriate conditions (very dry, sunny, well-drained) it will self-seed and naturalize gradually, which is generally desirable.

How do I grow Prince’s Plume from seed?

Sow seeds in fall outdoors for natural cold stratification and spring germination. Alternatively, cold-stratify seeds in moist sand in the refrigerator for 4–6 weeks, then plant in spring in a well-drained mix. Germination is typically good. Seedlings grow quickly and may flower in their second year. Thin to the strongest seedlings and plant out when they have a well-developed root system.

What is selenium hyperaccumulation?

Selenium hyperaccumulators are plants that take up and store selenium from the soil in their tissues at concentrations 100–1,000 times higher than surrounding plants. Prince’s Plume concentrates selenium in its leaves and stems as a defense against herbivory and possibly as a competitive mechanism against neighboring plants. Only about 700 plant species worldwide are known hyperaccumulators of any metal or metalloid.

Will Prince’s Plume grow outside its native range?

Prince’s Plume can be grown successfully outside its native range in any region with hot summers, cold winters, and well-drained soils — it performs well in xeriscape gardens throughout USDA Zones 4–9. It struggles in humid climates with wet winters, where crown rot is a risk. Gardeners in California, the Southwest, and the Mountain West have the best success.