Russet Buffaloberry (Shepherdia canadensis)

Shepherdia canadensis, commonly known as Russet Buffaloberry, Canadian Buffaloberry, or Soapberry, is one of the most ecologically important native shrubs of the northern Rocky Mountains and Intermountain West. This medium-sized deciduous shrub — typically growing 3–12 feet tall — is instantly recognizable by its distinctive leaves: blue-green above with silvery scales below and often dotted with russet (reddish-brown) specks, giving the plant a uniquely two-toned, shimmering appearance. The “rusty dots” are a defining characteristic that give the plant one of its common names and immediately distinguish it from similar shrubs in the field.

As a member of the Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster) family, Russet Buffaloberry has a remarkable botanical superpower: like its relatives the alders and legumes, it fixes atmospheric nitrogen through a symbiotic relationship with soil bacteria (Frankia spp.). This nitrogen-fixing ability allows it to thrive in poor, nutrient-deficient soils where other shrubs struggle, and makes it a soil-building pioneer species on disturbed and eroded sites. In natural succession, Russet Buffaloberry often establishes early and enriches soil conditions that allow subsequent species to colonize.

For wildlife, particularly grizzly and black bears, Russet Buffaloberry is critically important. The tart, translucent red to orange-red berries — born in abundance on female plants — are a major food source for bears in late summer, and some of the most dramatic “bear berry” viewing in the Rocky Mountain parks occurs at Russet Buffaloberry thickets during berry season. Dozens of other bird and mammal species also consume the berries. Despite their tart, slightly bitter flavor, the berries have a rich traditional use as a food plant by Indigenous peoples throughout the northern Rockies.

Identification

Russet Buffaloberry grows as a multi-stemmed deciduous shrub, 3–12 feet (1–3.6 m) tall with a similar spread, forming dense thickets in favorable conditions. The twigs are distinctive: covered with silvery or rusty scales that give them a star-pattern appearance under magnification. The plant is dioecious — male and female flowers on separate plants — and only female plants produce berries.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, opposite, 1–2.5 inches long, oval to elliptical. The upper surface is blue-green, initially covered with silvery scales that partially wear off to reveal the green surface as the season progresses. The lower surface retains a dense covering of silvery scales mixed with characteristic russet (reddish-brown) dots or scales — this “rusty underside” pattern is the most reliable field identification feature. The combination of silver-green upper surface and rusty-spotted lower surface gives the leaves a beautiful two-toned shimmering effect when they move in the wind.

Flowers & Fruit

The flowers are tiny, 4-petaled, yellowish-green, and appear before or with the leaves in early spring (April–May). Male and female flowers occur on separate plants. The fruits are small drupes (berries), ¼ to ⅜ inch in diameter, translucent red to orange-red when ripe, often with rusty specks. The berries are tart, somewhat bitter, and described as soapy due to saponin content — hence one common name, “Soapberry.” They ripen in late July through September, often in dense clusters on female plants. Despite their bitterness, they are eaten by bears, birds, and many mammals, and were prepared as food by Indigenous peoples through cooking and processing.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Shepherdia canadensis |

| Family | Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous shrub, nitrogen-fixing |

| Mature Height | 3–12 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Yellowish-green (tiny, inconspicuous) |

| Fruit | Red to orange-red drupes (July–September) |

| Wildlife Value | Critical for bears, birds, mammals; nitrogen-fixer |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

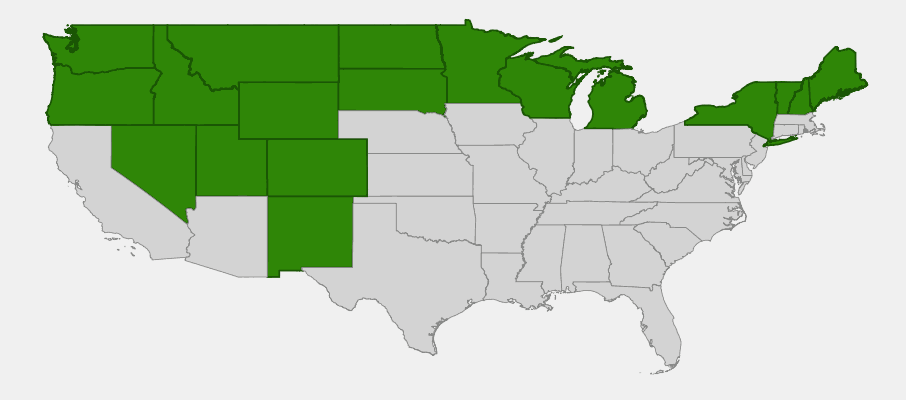

Native Range

Russet Buffaloberry is native to an exceptionally wide range across northern North America, making it one of the most cold-hardy and ecologically widespread native shrubs of the continent. In the United States, it ranges from the northern Rocky Mountain states (Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada) across the northern Great Plains (North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska) and upper Midwest (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan) to the northeastern states (New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine). This enormous range spans from western mountain ecosystems to eastern boreal and mixed deciduous forests.

In the Intermountain West, Russet Buffaloberry is primarily a mountain and subalpine species, occurring from moderate elevations in the foothills and montane zones (4,000–6,000 ft) up to timberline at 10,000+ feet. It is particularly abundant in Rocky Mountain National Park, Glacier National Park, Yellowstone, and Banff-Jasper, where the dense berry crops are legendary as bear food. The species tolerates cold temperatures to -50°F or below — making it suitable for even the harshest interior mountain climates.

Within the Intermountain West, Russet Buffaloberry most commonly grows in mountain shrubland communities alongside serviceberries, chokecherry, willow, alder, and in the understory of montane conifer forests (lodgepole pine, Douglas-fir, aspen). It frequently colonizes disturbed areas including roadsides, cutover forest areas, and areas recovering from fire — a function of both its nitrogen-fixing ability and its tolerance for poor soil conditions.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Russet Buffaloberry: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Russet Buffaloberry is exceptionally cold-hardy, adaptable, and low-maintenance — an excellent native shrub for wildlife gardens, erosion control, and naturalistic plantings in mountain and northern settings.

Light

Russet Buffaloberry performs well in full sun to part shade. In full sun, it produces the most berries and develops the densest, most compact growth form. In partial shade (particularly in forest edges), it grows more open but remains healthy and productive. It is one of the more shade-tolerant shrubs that also produces significant fruit crops — a valuable combination for forest-edge plantings.

Soil & Water

One of this shrub’s most important attributes is its ability to grow in poor, nutrient-deficient soils that defeat most other plants. Its nitrogen-fixing root nodules (Frankia bacteria) allow it to enrich the soils in which it grows — making it particularly valuable for disturbed site rehabilitation. It grows well in sandy, gravelly, rocky, or loamy soils and handles both acidic and moderately alkaline conditions. Once established, it is moderately drought tolerant and rarely needs supplemental irrigation in its native mountain climate (typically 15–25 inches of annual precipitation). During establishment, water weekly for the first season. The plant is not suitable for heavy, poorly-drained soils.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring or fall. Because plants are dioecious (male and female are separate), you need at least one male plant near female plants for fruit production. Purchase plants from reputable native nurseries and ask about the sex of plants; many nurseries sell unnamed stock of mixed sex. A common recommendation is 1 male per 3–5 females for good berry production. Spacing should be 6–10 feet for naturalistic plantings or 4–6 feet for denser hedgerows. The plants spread by suckers and can form naturalistic thickets over time.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal pruning is needed. Remove dead wood and suckers that extend beyond desired boundaries in early spring. If plants become overly dense, thin by removing one-third of the oldest stems at the base — the plant regenerates vigorously. Russet Buffaloberry is resistant to most pests and diseases, though aphids occasionally feed on new growth without causing serious damage. Deer browse the foliage but the plant typically regenerates well after browsing.

Landscape Uses

- Wildlife garden — essential for bear, bird, and mammal habitat

- Erosion control and slope stabilization

- Revegetation and disturbed site rehabilitation

- Nitrogen-fixing pioneer species in restoration projects

- Native hedgerow or screen — forms dense, wildlife-attracting thickets

- Forest edge planting — tolerates shade from adjacent trees

- Mountain and subalpine gardens — extremely cold hardy to Zone 2

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Russet Buffaloberry is one of the most ecologically important native shrubs of the Rocky Mountains and boreal North America, providing food, cover, and soil enrichment across its extensive range.

For Bears

Perhaps no plant is more strongly associated with bear nutrition in the Rocky Mountains than Russet Buffaloberry. Grizzly Bears and Black Bears consume enormous quantities of the berries in late summer and fall — the period of hyperphagia (intense pre-hibernation eating) when bears may consume 20,000 calories per day. In Glacier National Park and Yellowstone, bear viewing at Russet Buffaloberry patches is a major wildlife tourism draw. The timing of berry ripening (July–September) coincides perfectly with the critical pre-hibernation fattening period, making this plant indispensable to bear populations throughout the northern Rockies.

For Birds

The berries are consumed by American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Bohemian Waxwings, Swainson’s Thrushes, and numerous other frugivorous birds. The dense thickets provide excellent nesting cover for White-crowned Sparrows, Yellow Warblers, MacGillivray’s Warblers, and various other shrub-nesting species. The early spring flowers provide modest early-season pollen and nectar for native bees.

For Other Mammals

Elk, Mule Deer, and Moose browse the stems and foliage. Coyotes, foxes, and small carnivores eat the berries. Squirrels and chipmunks collect the berries for caching. The thickets provide important thermal cover and bedding habitat for ungulates in mountain environments.

Ecosystem Role

As a nitrogen-fixing shrub, Russet Buffaloberry enriches the soils in which it grows, facilitating the establishment and growth of non-fixing plant species nearby. In post-fire and post-disturbance succession, it is often one of the first woody species to establish, creating conditions for more demanding forest species to follow. The dense thickets help stabilize eroding slopes and maintain soil moisture, playing a key structural role in mountain shrubland and forest-edge ecosystems.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Russet Buffaloberry has been used as a food plant by Indigenous peoples throughout its range, though preparation is essential because raw berries contain saponins that cause the slightly soapy taste and can cause gastrointestinal distress if eaten in quantity. The most famous traditional use is “Indian Ice Cream” — a frothy, traditional treat prepared by the Blackfoot, Cree, Interior Salish, and many other nations. Fresh or dried berries are combined with water and beat vigorously (the saponins make the mixture foam like soap), sometimes with the addition of salmon oil, sugar, or other sweeteners, creating a distinctive foam that was served at feasts and celebrations. The technique is still practiced today as a cultural tradition and symbol of Indigenous identity in Canada and the northern United States.

Beyond the iconic foamed preparation, Russet Buffaloberry berries were eaten fresh (despite bitterness), dried and stored for winter, boiled into sauces, and mixed with other foods including dried meat and fish. The berries were harvested in large quantities using traditional methods — branches were beaten over hides or containers to knock the berries loose quickly. The berries were also used medicinally — preparations were used for constipation, as a laxative, for treating venereal diseases, and as a general tonic.

The plant also had non-food uses: preparations of the stems and bark were used medicinally for constipation and liver complaints by various tribes. Modern research has identified numerous bioactive compounds in Shepherdia canadensis berries including lycopene, carotenoids, quercetin, and other antioxidants, confirming the nutritional value of this important traditional food plant.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you eat Russet Buffaloberry berries?

Yes, but they require preparation. Raw berries are quite tart and bitter due to saponin content. Cooking, drying, or the traditional “Indian Ice Cream” preparation significantly improves palatability. Do not eat large quantities of raw berries — the saponins can cause nausea and gastrointestinal upset in sensitive individuals. The cooked or processed berries are nutritious and have been an important traditional food for millennia.

Is Russet Buffaloberry the same as Silver Buffaloberry?

No — they are different species. Russet Buffaloberry (Shepherdia canadensis) lacks thorns and grows primarily in mountain and boreal habitats. Silver Buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea) is a thorny shrub of river bottoms and plains. Both have similar leaf color and berry appearance, but Russet Buffaloberry is taller and more broadly distributed across northern North America.

Do I need both male and female plants?

Yes — Russet Buffaloberry is dioecious; only female plants produce berries, and males are needed for pollination. Plant at least one male for every 3–5 females. Unfortunately, sex cannot be determined until the plant flowers for the first time (after 3–5 years from seed). Buying multiple plants from a reputable nursery that sells sexed stock is recommended.

How do I grow Russet Buffaloberry from seed?

Seeds require cold stratification — store moist seeds at 34–40°F for 60–90 days before sowing. Alternatively, sow fresh seeds outdoors in fall and allow natural winter stratification. Germination can be erratic and may take 1–2 years. Container-grown transplants from native nurseries are usually more reliable for garden establishment.

Will Russet Buffaloberry attract bears to my yard?

In areas with bear populations, yes — a heavily berry-laden Russet Buffaloberry in a backyard setting could attract bears. In such areas, use the plant in more remote or less frequented parts of the property, or harvest berries as they ripen. The bear attraction is generally considered a positive ecological feature in wildland restoration settings.