Squawbush Sumac (Rhus trilobata)

Rhus trilobata, commonly known as Squawbush Sumac, Skunkbush Sumac, Lemonade Berry, or Three-leaf Sumac, is a tough, aromatic native shrub found across the Intermountain West, Rocky Mountains, and Great Plains. A member of the Anacardiaceae (cashew/sumac) family and close relative of Fragrant Sumac (R. aromatica), this drought-tolerant deciduous shrub is distinguished by its three-lobed, strongly aromatic leaves, showy red berry clusters, and spectacular scarlet to deep red fall foliage. The species name trilobata means “three-lobed,” referring to the distinctive trifoliate leaf arrangement.

Despite its somewhat unfortunate common names (the “skunk” in Skunkbush refers to the pungent, resinous smell of the crushed leaves), Squawbush Sumac is an extraordinarily valuable native plant. Its dense, low-spreading habit makes it excellent for erosion control and slope stabilization; its red berries provide important food for birds throughout fall and winter; and its fall foliage color is among the best of any dry-climate native shrub. The dried berries have a sour, lemony flavor and were widely used by Indigenous peoples to make a refreshing beverage — explaining the alternative name “Lemonade Berry.”

For gardeners and land managers in the Intermountain West, Squawbush Sumac is a top-tier choice for challenging sites. It grows on steep, dry slopes, rocky outcrops, sandy washes, and alkaline flats where most ornamental shrubs cannot survive. Its multi-season interest (spring flowers, summer foliage, fall berries and color), wildlife value, and near-zero maintenance requirements make it one of the most practical native shrubs for the region. Increasing water scarcity and the growing interest in xeriscape design have driven renewed appreciation for this undervalued native.

Identification

Squawbush Sumac grows as a spreading to mounded, multi-stemmed deciduous shrub, typically 2 to 6 feet (60–180 cm) tall and often wider than tall. The stems are reddish-brown and somewhat hairy when young. The plant spreads by underground rhizomes, forming dense colonies over time. When any part of the plant is crushed or bruised, it releases a strong, resinous, somewhat skunky aroma that is distinctive and memorable — though opinions differ on whether it is pleasant or unpleasant.

Leaves

The leaves are the most distinctive identification feature: each leaf is divided into three rounded, lobed leaflets, somewhat resembling poison ivy in general arrangement (but Squawbush Sumac is not toxic — it belongs to the non-toxic Rhus group, not the toxic Toxicodendron group). The leaflets are hairy, dark green above, paler beneath, and strongly aromatic when crushed. Fall color is outstanding — foliage turns brilliant shades of scarlet, orange, and red, among the most vivid fall color of any Intermountain West native shrub.

Flowers

The flowers appear before or with the leaves in early spring (March–May), in dense, catkin-like, yellowish spikes at the branch tips. Individual flowers are tiny, but the mass of spike-like inflorescences covering the bare branches before leaf-out creates a subtle but attractive early-season display. The flowers are wind- and insect-pollinated.

Fruit

The fruits are small, round, sticky-hairy drupes, about ¼ inch (6 mm) in diameter, that ripen in clusters from green through orange to bright red by late summer. The red fruits are covered with sticky, acid hairs and have a sour, citric flavor. They persist on the plant through winter, gradually drying and turning brownish-red, providing food for birds when other food sources are scarce.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Rhus trilobata |

| Family | Anacardiaceae (Cashew/Sumac) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 2–6 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Very Low (Xeric/Extremely Drought Tolerant) |

| Bloom Time | March – May (before leaves) |

| Flower Color | Yellowish (inconspicuous catkins) |

| Fall Color | Brilliant scarlet, orange, red |

| Fruit | Red sticky berry clusters (summer–winter) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

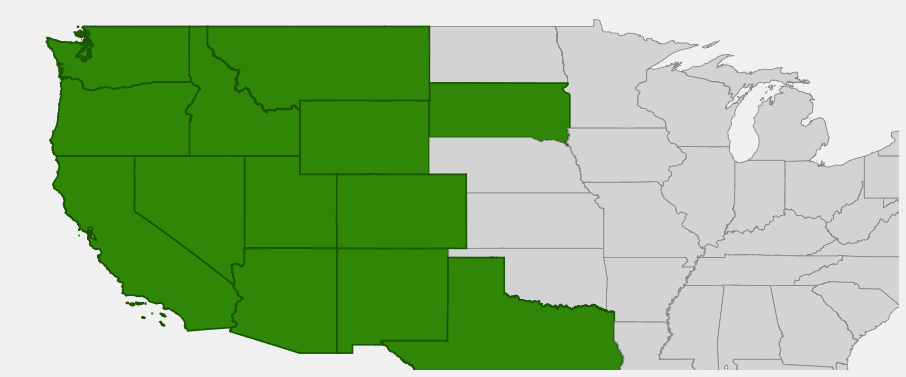

Native Range

Squawbush Sumac is native to much of the western and central United States, ranging from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana south through California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas, and east across the Great Plains through Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. It also extends into northern Mexico. The species grows from near sea level to 8,000 feet elevation and is found in an extraordinary diversity of habitats, from coastal California chaparral to high desert scrub and Great Plains rocky outcrops.

In the Intermountain West, Squawbush Sumac is most commonly found on dry, rocky slopes, canyon walls, desert washes, and the edges of pinyon-juniper woodland. It is frequently associated with Big Sagebrush, Bitterbrush, Gambel Oak, and various native bunchgrasses. In the Colorado Plateau and Four Corners region, it is one of the most conspicuous and widespread shrubs, forming dense thickets on canyon rims and rocky slopes throughout. It is also common on disturbed sites such as roadsides, abandoned fields, and overgrazed rangeland, where its rhizomatous growth habit allows it to spread and stabilize bare soil.

The extraordinary geographic range of Squawbush Sumac reflects its exceptional physiological tolerance. It grows in areas receiving as little as 6 inches of annual precipitation and as much as 25 inches; tolerates soils ranging from pure sand to heavy clay to rocky limestone; and survives temperature extremes from –40°F (–40°C) to 110°F (43°C). This flexibility makes it one of the most reliable native shrubs for challenging sites across an enormous range of western climates.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Squawbush Sumac: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Squawbush Sumac is one of the most xeric, low-maintenance native shrubs available for dry-climate western gardens. Once established, it thrives on neglect — asking only for sun, good drainage, and freedom from overwatering.

Light

Full sun is ideal for Squawbush Sumac. It grows best with 6–8 or more hours of direct sun, which produces the densest growth, best berry crops, and most vivid fall color. It tolerates partial shade but becomes more open and less vigorous, with reduced fruiting. In deep shade, the plant is not suitable.

Soil & Water

Squawbush Sumac is among the most drought-tolerant native shrubs of the Intermountain West, adapted to thin, rocky, and nutrient-poor soils. It grows well in sandy, gravelly, loamy, or clay soils as long as drainage is reasonable. Once established (1–2 years), it requires no supplemental irrigation in most western climates. During establishment, water deeply but infrequently. The rhizomatous root system is excellent at anchoring dry, eroding slopes.

Planting Tips

Plant in spring or fall from container stock. Choose a sunny, well-drained site. Space plants 4–6 feet apart — they will spread by rhizomes to form a dense colony, which is ideal for erosion control or wildlife habitat. For formal garden use, plant one or a few specimens and remove suckers as needed to control spread. Squawbush Sumac can also be grown from hardwood cuttings or division of existing colonies.

Pruning & Maintenance

Squawbush Sumac is very low-maintenance. The plant can be cut to the ground in late winter to rejuvenate it and produce vigorous new growth with the best fall color. Otherwise, it needs only the removal of dead stems and occasional thinning of the densest thickets. The aromatic foliage deters most browsing animals, but jackrabbits and deer may graze young stems in drought years.

Landscape Uses

- Dry slope erosion control — rhizomatous roots stabilize banks and slopes

- Bird gardens — red berries attract many bird species through winter

- Fall color — spectacular scarlet and orange autumn foliage

- Xeriscape borders and mass plantings in full sun

- Naturalized areas and wildlife habitat plantings

- Windbreaks and screens in exposed, dry locations

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Squawbush Sumac is a high-value wildlife plant in the arid West, providing food and cover for birds throughout the fall and winter months when other food sources have been depleted.

For Birds

The red berry clusters are consumed by a wide variety of birds, including American Robin, Hermit Thrush, Western Bluebird, Mountain Bluebird, Cedar Waxwing, Townsend’s Solitaire, Scrub-Jay, and many sparrow and finch species. Critically, the berries persist through the winter months, providing emergency food during cold spells when insect prey is unavailable. The dense, low thickets provide essential escape and thermal cover for ground-nesting and low-nesting birds including California Quail, Gambel’s Quail, and Chukar.

For Mammals

Mule Deer, Pronghorn, and Elk browse the foliage and twigs, particularly in early spring when high-protein new growth is available. Black Bears, Coyotes, and Foxes consume the berries. Jackrabbits and cottontails browse the stems in winter. The dense thicket habitat provides excellent cover for cottontails, ground squirrels, and other small mammals.

For Pollinators

The early spring flowers (appearing before the leaves) are among the first available nectar sources of the season, providing critical early food for emerging native bees. Mining bees, sweat bees, and bumble bees are frequent visitors. The flowers bloom at a time when pollinators are hungry and food is scarce, making Squawbush Sumac an important early-season resource.

Ecosystem Role

Squawbush Sumac is an important soil-building and slope-stabilizing plant in the arid West. Its rhizomatous root system binds eroding soils on dry slopes and canyon walls. The dense leaf litter adds organic matter to poor soils. The thicket structure increases habitat complexity in open desert shrubland, providing nesting substrate and food resources for invertebrates, reptiles, birds, and small mammals. In recovering post-fire landscapes, Squawbush Sumac resprouts vigorously from the root system, helping to stabilize soils and initiate vegetation recovery quickly.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Squawbush Sumac was one of the most important multi-use plants for Indigenous peoples of the American West, Southwest, and Great Plains. The sour, sticky red berries were a significant food source for the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Shoshone, Paiute, Ute, Apache, and numerous other nations. The berries were eaten fresh (despite the strong sour taste), dried for winter storage, ground into a meal, or most commonly soaked in water to make a tart, lemonade-like beverage — hence the name “Lemonade Berry.” The drink was popular as a summer refresher and was also used medicinally to treat fevers and sore throats.

The long, flexible young shoots of Squawbush Sumac were one of the most prized basketry materials in western North America. The Panamint Shoshone, Cahuilla, Luiseño, and many Plateau and Great Basin peoples wove baskets, burden baskets, seed beaters, and other items from Squawbush stems — and Squawbush-woven baskets are among the finest examples of Indigenous basketry in museum collections worldwide. The stems were harvested in late summer, split longitudinally, and worked while still green before drying to create smooth, flexible weaving material. The reddish bark of the stems added color variation to basket designs.

Medicinally, bark preparations were used to treat skin ailments, infections, and stomach complaints. The leaves and berries were used in various ceremonial contexts. In modern horticulture, Squawbush Sumac is increasingly valued for its fall color, drought tolerance, and wildlife value, and is available at native plant nurseries throughout the West. Its rhizomatous growth habit makes it especially useful for large-scale revegetation and slope stabilization projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Squawbush Sumac the same as Poison Ivy?

No — Squawbush Sumac (Rhus trilobata) is completely different from Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Both have three-leaflet leaves, but they belong to different genera. Rhus species are non-toxic; Toxicodendron species contain urushiol and cause allergic reactions. Squawbush Sumac is safe to handle and its berries are edible.

Why is it called Skunkbush?

The strong, resinous, somewhat pungent aroma of the crushed leaves earned it the nickname “Skunkbush.” Opinions on the smell vary — some people find it unpleasant; others find it pleasant or mildly spicy. The smell comes from volatile terpene compounds in the leaves. It is not related to actual skunk spray.

Will Squawbush Sumac spread and take over?

Squawbush Sumac spreads by underground rhizomes and can form large colonies over time — which is desirable for erosion control and wildlife habitat, but should be considered when planting in formal gardens. It can be managed by mowing or removing suckers at the edges of the desired planting area. It is not invasive in the ecological sense — it is native and supports the local ecosystem.

Can I eat Squawbush berries?

Yes, the berries are edible and have been used as a food source by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. They are extremely tart and sour, with a citric acid-like flavor. They are best used to make a refreshing drink (soak berries in water for 30 minutes, strain, add honey) rather than eaten raw in quantity. They are not toxic in any way.

When does Squawbush Sumac show its best fall color?

Fall color typically begins in September–October and can be spectacular — vivid scarlet to deep red foliage that can rival the color of ornamental maples. The intensity of fall color is greatest in full-sun sites with significant day/night temperature differentials, typical of Intermountain West fall weather.