Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

Platanus occidentalis, commonly known as the American Sycamore, Buttonwood, or simply Sycamore, is one of North America’s most distinctive and largest native deciduous trees. This magnificent member of the Platanaceae (plane tree) family can reach towering heights of 75 to 100 feet or more, with massive trunks that can exceed 14 feet in diameter, making it among the largest hardwood trees in eastern North America. The species is instantly recognizable by its mottled bark that exfoliates in irregular patches, revealing a striking camouflage-like pattern of cream, gray, and brown colors.

Growing naturally along floodplains, riverbanks, and low-lying areas throughout the eastern United States, the American Sycamore is equally at home in wet bottomlands and well-drained upland sites. Its enormous, broadly palmate leaves — often 4 to 10 inches across — provide dense summer shade, while its distinctive spherical seed heads, called “buttonballs,” dangle from branches through winter, giving the tree its alternate name of Buttonwood. These seed balls, typically 1 to 1.5 inches in diameter, eventually break apart to release hundreds of tiny seeds equipped with bristly hairs that aid in wind dispersal.

Beyond its impressive stature and distinctive appearance, the American Sycamore serves critical ecological functions, supporting numerous wildlife species and providing important environmental services. Its hollow trunks often serve as den sites for raccoons, opossums, and wood ducks, while its seeds feed songbirds through winter. The species’ rapid growth, flood tolerance, and ability to stabilize streambanks make it invaluable for riparian restoration projects and erosion control throughout its extensive native range.

Identification

The American Sycamore is among the most easily identified trees in North America, thanks to several distinctive characteristics that remain consistent across seasons and growing conditions.

Bark

The most distinctive feature of the American Sycamore is its remarkable bark pattern. On mature trees, the outer bark exfoliates (peels off) in irregular plates and patches, revealing smooth inner bark in contrasting colors. This creates a striking mottled or camouflage-like appearance with patches of brown, gray, green, and creamy white or tan colors. The bark pattern is so distinctive that the tree can be identified from considerable distances, even in winter when leaves are absent. Young trees and branches have brown bark that hasn’t yet begun to exfoliate, but the characteristic mottling develops as trunks mature and expand.

Leaves

Sycamore leaves are large, simple, and alternate, typically measuring 4 to 10 inches across — among the largest simple leaves of any North American tree. The leaves are broadly palmate with 3 to 5 shallow, pointed lobes separated by broad, rounded sinuses (the spaces between lobes). The leaf base is broadly heart-shaped to truncate, and the margins have large, coarse teeth. The upper surface is bright green and smooth, while the underside is paler and may be slightly fuzzy when young. Leaf petioles are long (2 to 6 inches) and stout, often with a swollen base that encircles the twig. Fall color is typically yellow-brown, though not particularly showy.

Flowers & Fruit

American Sycamore is monoecious, meaning individual trees bear both male and female flowers. The tiny, inconspicuous flowers appear in dense, spherical heads in early spring before the leaves emerge. Male flower heads are small (about ¼ inch across) and yellowish-green, while female flower heads are larger (about ½ inch) and reddish. The flowers are wind-pollinated and lack petals, appearing as dense clusters of stamens or pistils.

The fruit develops from the female flower heads into the characteristic “buttonballs” or seed balls that make sycamores so recognizable. These spherical structures are typically 1 to 1.5 inches in diameter and hang singly from long stalks (distinguishing American Sycamore from London Planetree, which typically has 2 or more balls per stalk). The seed balls persist through winter, gradually breaking apart to release hundreds of small achenes (dry, single-seeded fruits) equipped with bristly hairs that aid in wind dispersal.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Platanus occidentalis |

| Family | Platanaceae (Plane Tree) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Tree |

| Mature Height | 70–100 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate to High |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow to reddish |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–9 |

Native Range

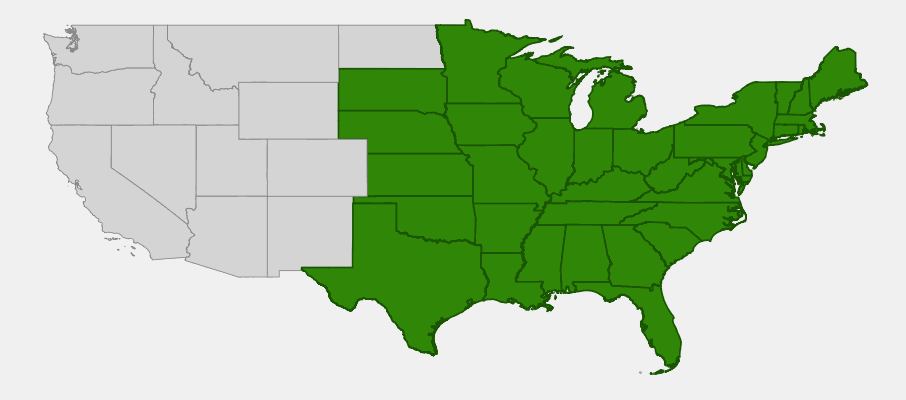

The American Sycamore has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American tree, stretching from southern Maine and southern Quebec south to northern Florida, and west to southeastern Nebraska, eastern Kansas, Oklahoma, and central Texas. The species is most abundant in the eastern United States, particularly in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, where it forms extensive bottomland forests along major waterways. It naturally occurs from sea level to elevations of about 2,000 feet, though it reaches its largest size in the rich alluvial soils of river floodplains.

In its natural habitat, American Sycamore is typically found along streams, rivers, floodplains, and in other low-lying areas with consistent moisture. It thrives in the deep, fertile, well-drained to somewhat poorly drained soils that characterize bottomland hardwood forests. The species is particularly well-adapted to periodic flooding and can tolerate extended periods of standing water, making it a dominant component of riparian ecosystems throughout the eastern and central United States.

Historically, American Sycamores of enormous size were common throughout their range, with some specimens reaching trunk diameters of 15 feet or more. While such giants are now rare due to logging and habitat conversion, the species remains locally common in appropriate habitats and continues to be one of the most characteristic trees of eastern North American floodplains.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring American Sycamore: New York, Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Growing & Care Guide

The American Sycamore is generally easy to grow and remarkably adaptable, though it performs best when its natural preferences for ample moisture and space are accommodated. Its rapid growth rate and impressive mature size make it an excellent choice for large properties, parks, and restoration projects.

Light

American Sycamore thrives in full sun but can tolerate partial shade, especially when young. In natural settings, mature sycamores often tower above surrounding vegetation, forming part of the forest canopy. For optimal growth and form, plant in locations that receive at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily. In shadier conditions, the tree may develop a more open, irregular crown and slower growth rate.

Soil & Water

This species is remarkably adaptable to various soil types but performs best in deep, fertile, well-drained to somewhat poorly drained soils with consistent moisture. Sycamores can tolerate clay soils, occasional flooding, and brief periods of standing water — characteristics that make them invaluable for riparian plantings and wet sites where other large trees struggle. However, they also adapt well to drier upland sites once established, though growth may be slower in such conditions. The ideal soil pH range is 6.0 to 8.0, but the species tolerates a wide range of soil chemistry.

Planting Tips

Plant American Sycamore in fall or early spring while the tree is dormant. Choose a location with ample space — remember that mature trees can reach 75-100 feet tall with canopy spreads of 60-80 feet or more. Space trees at least 40-50 feet from buildings and power lines. The species transplants readily as a young tree but can be challenging to move once established due to its rapid development of a large root system. Plant container-grown or balled-and-burlapped stock, ensuring the root flare is at or slightly above soil level.

Pruning & Maintenance

Young sycamores benefit from formative pruning to establish good structure, but mature trees require minimal maintenance. Remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter while the tree is dormant. The species tends to develop a strong central leader naturally, but competing leaders should be removed early. Be aware that sycamores are susceptible to anthracnose, a fungal disease that can cause leaf browning and defoliation in spring — while unsightly, this rarely threatens tree health. The species is also prone to developing hollow trunks with age, which provides wildlife habitat but may create structural concerns in urban settings.

Landscape Uses

American Sycamore serves multiple landscape functions:

- Shade tree for large properties, parks, and commercial landscapes

- Riparian restoration and streambank stabilization projects

- Wildlife habitat — hollow trunks provide nest sites for wood ducks and other cavity-nesting species

- Erosion control on slopes and flood-prone areas

- Specimen tree showcasing distinctive bark and massive scale

- Reforestation projects in bottomland and floodplain areas

- Urban forestry in suitable large-scale settings (parks, golf courses, etc.)

Wildlife & Ecological Value

The American Sycamore provides exceptional wildlife value and serves as a keystone species in riparian ecosystems throughout its range. Its large size, long lifespan, and diverse habitat offerings support numerous species across multiple wildlife groups.

For Birds

Sycamores are particularly valuable for cavity-nesting birds. The species’ tendency to develop hollow trunks and large cavities makes it a preferred nesting site for Wood Ducks, which nest in tree cavities near water. Other cavity nesters that utilize sycamores include various woodpecker species, nuthatches, chickadees, and flying squirrels. The seeds from buttonballs feed finches, chickadees, and other small songbirds through winter, while the tree’s large canopy provides important roosting and nesting habitat. Migrating waterfowl often rest in sycamores along major flyways, particularly those growing near water.

For Mammals

The large cavities that develop in mature sycamores provide den sites for raccoons, opossums, and squirrels. These hollow spaces are particularly valuable as winter shelter and nursery sites. Bats use loose bark and cavities for roosting, while various small mammals consume the seeds. White-tailed deer occasionally browse young shoots and leaves, though the tree is not a preferred food source.

For Pollinators

While not particularly showy, sycamore flowers provide early spring nectar and pollen for bees and other insects. The flowers bloom before most other trees leaf out, making them an important early-season resource. The tree also supports various moth and butterfly larvae, including the American Dagger Moth and various sphinx moths.

Ecosystem Role

American Sycamore plays crucial ecological roles in riparian and floodplain ecosystems. Its extensive root system helps stabilize streambanks and reduce erosion, while its large canopy moderates stream temperatures and provides shade for aquatic organisms. The tree’s tolerance for flooding and its ability to trap sediment during flood events make it invaluable for natural flood control and water quality improvement. Sycamore leaf litter decomposes relatively quickly, contributing nutrients to aquatic and terrestrial food webs. The species also serves as a nurse tree, providing favorable microclimatic conditions for the establishment of other forest species.

Cultural & Historical Uses

The American Sycamore holds a distinguished place in North American cultural and natural history, serving indigenous peoples for millennia and playing important roles in early European settlement. Native American tribes throughout the tree’s range utilized virtually every part of the sycamore for practical purposes. The Cherokee, Creek, and other southeastern tribes used the soft, easily worked wood for dugout canoes — some sycamore canoes were large enough to carry 20 or more people. The hollow trunks of large sycamores served as temporary shelters and food storage, while the inner bark was processed into cordage and textiles.

European colonists quickly recognized the value of sycamore wood for various applications. The wood is lightweight yet strong, with an attractive grain pattern that takes stain well. It became popular for furniture making, particularly for drawer sides and hidden structural elements where its workability was more important than appearance. Sycamore wood was also extensively used for butcher blocks, wooden bowls, and other kitchen implements because it doesn’t impart flavor to food and is easily sanitized.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, sycamore wood found industrial applications in textile mills for bobbins and spools, as its smooth grain reduced friction and wear on delicate threads. The wood’s shock-resistant properties made it suitable for tool handles, while its light color and even grain made it popular for painted furniture and trim work. Today, sycamore wood continues to be used for furniture, cabinetry, and specialty wood products, though it’s less commonly harvested than in previous eras.

Beyond its practical uses, the American Sycamore has captured imaginations as a symbol of strength and longevity. Several historic sycamores have achieved fame, including the Pringle Tree in West Virginia, which had a trunk circumference of over 47 feet. The species appears in American literature and folklore as a symbol of the wilderness and natural grandeur, often representing the untamed American landscape in poetry and prose of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Frequently Asked Questions

How fast do American Sycamores grow?

American Sycamores are among the faster-growing native trees, often adding 2-3 feet in height and significant trunk diameter annually under favorable conditions. Young trees in ideal sites with ample moisture and full sun can grow even faster, sometimes reaching 30-40 feet tall within 10-15 years.

Are Sycamores messy trees?

Sycamores do drop leaves, bark pieces, twigs, and buttonballs throughout the year, making them unsuitable for small spaces or areas where cleanliness is a priority. However, this natural debris provides wildlife habitat and eventually decomposes to enrich the soil. They’re best suited for naturalistic settings where some messiness is acceptable.

Why do Sycamore leaves turn brown in late spring/early summer?

This is typically caused by anthracnose, a fungal disease that affects sycamores in cool, wet spring weather. While the browning leaves look alarming, anthracnose rarely kills healthy trees. Affected trees usually produce new leaves later in the season and recover fully. The disease is more cosmetic than harmful in most cases.

Can Sycamores be planted near houses?

Due to their enormous mature size (75-100+ feet tall with wide-spreading crowns), sycamores should be planted at least 40-50 feet from structures. Their large surface roots can also potentially interfere with foundations, sidewalks, and utility lines if planted too close. They’re better suited for large properties, parks, or open spaces.

How can I tell American Sycamore from London Planetree?

The most reliable difference is the seed balls: American Sycamore typically has single buttonballs hanging from each stalk, while London Planetree usually has 2 or more balls per stalk. American Sycamore also tends to have more pronounced bark mottling and slightly larger leaves with deeper lobes, though these characteristics can overlap.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries American Sycamore?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: New York · Pennsylvania