Western Larch (Larix occidentalis)

Larix occidentalis, commonly known as Western Larch or Western Tamarack, is one of the most extraordinary conifers in North America — a deciduous conifer that sheds its needles every fall, turning the mountains of the northern Rocky Mountains and Cascades into a spectacular display of gold each October. The tallest larch species in North America, Western Larch can reach 150 feet (45 m) or more in height, with straight, massive trunks up to 4 feet in diameter that make it one of the most valuable timber trees of the inland Pacific Northwest.

What makes Western Larch truly unique is its paradoxical nature: it is a conifer that behaves like a deciduous tree. Each spring, delicate, bright-green tufts of needles emerge from stubby, knob-like spurs on the branches, clothing the tree in soft green through summer. By October, the needles turn a brilliant, luminous gold before dropping entirely — leaving the straight, reddish-bark trunk and bare branches to stand through winter like a sculptural monument to the mountain landscape. This golden fall display is a much-anticipated annual event in western Montana, northern Idaho, and the Cascades of Washington and Oregon.

Beyond its extraordinary visual presence, Western Larch is one of the most ecologically valuable conifers in the inland Pacific Northwest, supporting a diverse community of cavity-nesting birds and mammals, providing critical habitat through its large, fire-resistant trunks, and serving as a pioneer species after disturbance. For those with space for a large specimen tree, Western Larch is an unrivaled choice — a living landmark that connects garden, forest, and the rhythms of the season.

Identification

Western Larch is a tall, straight, narrowly conical to columnar deciduous conifer, reaching 100 to 150 feet (30–45 m) in height with a trunk diameter of 1.5 to 4 feet (45–120 cm) at maturity. The crown is narrow and open compared to most conifers. The trunk is distinctively straight and tapers gradually from a broad, buttressed base to a narrow crown. Young trees have a more conical form; older trees develop an irregular, open crown with the dead stubs of old branches still attached.

Bark

The bark is a key identification feature and one of Western Larch’s most attractive characteristics. Young trees have thin, grayish-brown bark with resinous blisters. As trees mature, the bark becomes very thick (up to 4 inches) and deeply furrowed into irregular, flat-topped plates, turning a rich reddish-brown to cinnamon color. This thick, fire-resistant bark is one of Western Larch’s most important ecological adaptations, allowing mature trees to survive low- and moderate-intensity fires that kill competing conifers.

Needles

The needles are 1 to 1¾ inches (2.5–4.5 cm) long, in tufts of 15 to 30 on short spur branches, and in spirals on new elongating shoots. They are bright yellowish-green in spring, blue-green in summer, turning brilliant gold to golden-yellow in October before falling. The spring needle emergence — delicate green tufts appearing on still-bare branches — is as spectacular in its own way as the autumn golden display. As a deciduous conifer, Western Larch goes through its entire annual cycle of growth, maturation, and dormancy, unlike most conifers that are evergreen.

Cones

The seed cones are small but distinctive: 1 to 1¾ inches (2.5–4.5 cm) long, cylindrical to ovoid, with distinctive long, slender bracts protruding well beyond the cone scales. These bracts give the cones a spiky, hedgehog-like appearance that is easily distinguished from other western conifers. Cones ripen in their first year and remain on the tree after releasing their winged seeds.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Larix occidentalis |

| Family | Pinaceae (Pine) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Conifer (Tree) |

| Mature Height | 150 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Fall Color | Brilliant gold (loses needles) |

| Bark | Thick, reddish-brown, fire-resistant |

| Longevity | 500–900 years |

| Wildlife Value | Very High — cavity nesters, seed eaters, raptors |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–7 |

Native Range

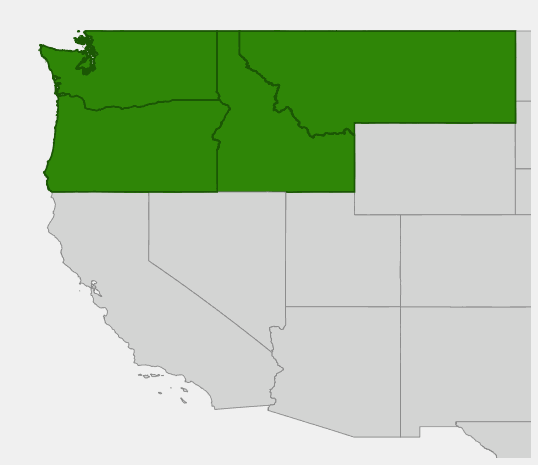

Western Larch has a relatively restricted native range compared to many western conifers, primarily occupying the inland mountains of the Pacific Northwest. It grows naturally in eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, northern Idaho, and western Montana, extending northward into the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia and Alberta. Within this range, it is typically found at elevations of 2,000 to 7,000 feet on well-drained, moderately moist mountain slopes, usually on north- and east-facing aspects where more moisture is available.

Western Larch is a characteristic tree of the inland Pacific Northwest mixed-conifer forest, growing in association with Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa), Grand Fir (Abies grandis), Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmannii), and Western White Pine (Pinus monticola). The species is notably intolerant of shade in its youth — it requires open, disturbed conditions to establish — making it a classic post-disturbance pioneer that is maintained in the landscape by periodic fire. Without fire or other disturbance, shade-tolerant conifers like Grand Fir gradually overtop and replace Larch.

The largest stands of Western Larch are found in the Bitterroot Mountains, Clearwater Mountains, and Kootenai National Forest of Montana and northern Idaho. In some valleys, particularly around Seeley Lake, Montana and the upper Flathead drainage, Western Larch is so dominant and its autumn color so spectacular that the region draws visitors from across the country each October specifically to witness the golden larch season. Hiking among large, ancient Larch trees with their massive reddish trunks and glowing gold canopies is an unforgettable experience.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western Larch: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Western Larch is a spectacular specimen tree for large, open landscapes in the northern Intermountain West. It is fast-growing for a large conifer (once established), long-lived, and requires minimal care after the establishment period. It is best suited to rural properties, large estates, acreages, and restoration projects — it is too large for most suburban lots.

Light

Full sun is essential. Western Larch is among the most light-demanding of the western conifers and will not thrive in shade. Young trees are particularly intolerant of shade — they require open, full-sun conditions to establish and grow vigorously. In its natural habitat, Larch establishes after fire or logging when the canopy has been opened up. Plant in the sunniest, most open location available.

Soil & Water

Western Larch prefers moderately moist, well-drained soils — it is not as drought-tolerant as Ponderosa Pine or the dry-site shrubs, but it is not as moisture-demanding as Grand Fir or Sitka Spruce. It grows best in deep, loamy soils on mountain slopes where seasonal snowmelt provides consistent moisture through summer. It does not tolerate flooding or prolonged waterlogging. In garden settings, provide moderate, consistent moisture during the first 3–5 years of establishment; once established, natural rainfall should be sufficient in most of its native range.

Planting Tips

Plant from container stock in fall or early spring. Choose the largest, most open area of your property — this tree ultimately reaches 100–150 feet. Space at least 20–30 feet from structures and other trees to allow for full crown development. Mulch the root zone generously with wood chips to retain soil moisture and moderate temperature extremes. Staking is generally not needed as Western Larch develops a strong, flexible trunk quickly.

Pruning & Maintenance

Western Larch requires very little pruning. Remove dead branches as needed. Lower branches naturally self-prune as the tree grows taller and the canopy shades them. Do not prune the central leader — this is essential for the naturally straight, tall form that is the species’ most distinctive characteristic. The tree is susceptible to a fungal pathogen (Meria laricis) that can cause needle cast in wet springs, but this is rarely fatal to healthy trees and typically resolves without treatment.

Landscape Uses

- Large specimen tree — unrivaled fall color; striking winter silhouette

- Restoration planting in post-fire or logged mixed-conifer forests

- Wildlife habitat trees — cavity nesters, raptors, seed-eating birds

- Windbreak on large rural properties

- Riparian buffers on moist mountain slopes

- Acreage and farm trees for shade, windbreak, and visual interest

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western Larch is a keystone tree species in the inland Pacific Northwest, providing critical habitat structure — particularly through large-diameter snags and live trees — that supports an extraordinary diversity of wildlife.

For Cavity Nesters

Large, old Western Larch are among the most important cavity trees in the inland Pacific Northwest. The thick, fire-scarred trunks develop cavities that are used by Pileated Woodpeckers, Northern Flickers, Hairy Woodpeckers, and other woodpecker species for nesting and foraging. These cavities are subsequently used by dozens of secondary cavity-nesting species including Northern Pygmy-Owl, Boreal Owl, Mountain Chickadee, Red-breasted Nuthatch, and various tree swallow species. The retention of large, old larch snags is a critical conservation priority in managed Pacific Northwest forests.

For Seed-Eating Birds & Mammals

The seeds are consumed by Crossbills (Red Crossbill and White-winged Crossbill), Pine Siskins, Chickadees, Clark’s Nutcrackers, and various other seed-eating birds. Red Squirrels and Douglas Squirrels (Chickarees) harvest and cache larch cones. The seeds are shed from late summer through fall and provide a burst of food resources during the critical pre-winter period.

For Raptors

The tall, emergent crowns of large Western Larch provide hunting perches and nest sites for Osprey, Bald Eagle, Red-tailed Hawk, and Northern Goshawk. In areas where Western Larch dominates the canopy, these trees are disproportionately used as raptor nest trees due to their height, structural strength, and open crown that provides good sightlines for hunting.

Ecosystem Role

Western Larch has a unique ecological role as a deciduous conifer: unlike evergreen conifers, it sheds its needles annually, creating a more nutrient-rich litter layer that decomposes faster than spruce or fir needles. This faster decomposition supports a more diverse soil fauna and a richer understory plant community beneath larch stands. The fire-resistant bark of large larch allows it to survive fires that kill competing conifers, making it a “biological legacy” species that provides structural continuity from pre-fire to post-fire forest conditions. Large, fire-resistant larch trees are critical for maintaining the genetic and ecological integrity of the inland Pacific Northwest forest through the disturbance cycles that characterize this ecosystem.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Western Larch has been important to Indigenous peoples of the inland Pacific Northwest for thousands of years. The Kalispel, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreilles peoples used the sweet, edible inner bark (cambium) as a food source in spring, when it could be peeled in strips and eaten fresh or dried. The sweet gum that exudes from wounds in the bark — called galactan or larch arabinogalactan — was chewed as a sweet treat and used medicinally as a cough remedy and wound treatment. The bark and wood were used for various tools, and the straight, strong wood was valued for construction of canoes, lodges, and implements requiring hard, rot-resistant timber.

Western Larch was one of the most important commercial timber species in the inland Pacific Northwest throughout the 20th century. The wood is dense, strong, and rot-resistant — prized for structural framing, flooring, furniture, and historically for telegraph poles, mine timbers, and railway ties. Large-scale logging of old-growth Western Larch stands throughout the 1900s significantly reduced the abundance of large, old trees, and protecting remaining old-growth larch is a major conservation focus in Idaho, Montana, and the Pacific Northwest.

Today, Western Larch is increasingly recognized for its ecological and aesthetic value beyond timber. The annual “larch season” in northwestern Montana and northern Idaho draws thousands of visitors each October who hike and drive through larch forests to witness the golden foliage display. The Larch Hills of British Columbia and the Enchantments area of Washington are famous hiking destinations specifically for their larch fall color. This growing cultural appreciation for larch as a living, aesthetic resource rather than simply a timber product is helping to drive conservation of old-growth larch forests across the region.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Western Larch really a conifer that loses its needles?

Yes — Western Larch is one of only a handful of deciduous conifers in the world. Like its relatives the Tamarack (Larix laricina) of eastern North America and the Siberian Larch (Larix sibirica), it grows needles each spring and drops them each fall. The annual needle cycle means it goes completely bare in winter, with just its straight trunk and branches remaining — a dramatic and beautiful silhouette.

How fast does Western Larch grow?

Western Larch is among the fastest-growing western conifers in appropriate conditions. Under ideal conditions (full sun, moderate moisture, good soil), young trees can grow 2–3 feet per year. Growth slows as trees mature. Even so, it takes many decades to develop the massive, old-growth character that makes ancient larch so spectacular. Plan for a 50–100 year perspective when planting larch.

Can I grow Western Larch outside its native range?

Western Larch grows well in USDA Zones 4–7 with adequate moisture and cold winters. It has been successfully planted in areas of Europe and New Zealand as an ornamental and timber tree. Outside its native range, it may be susceptible to disease and pest pressures to which it is not adapted, so consult local forestry extension services before planting large numbers.

When is the best time to see larch fall color?

In its core native range (northern Idaho and western Montana), peak golden color typically occurs in early to mid-October, though this varies by elevation and year. Higher-elevation sites color up first (late September); valley-bottom larch may hold green color into late October. The golden color is most intense in years with cold, clear fall weather following good summer moisture.

How long does Western Larch live?

Western Larch is a very long-lived tree. Individual trees commonly reach 500–700 years old, and some ancient individuals have been documented at over 900 years. These ancient trees, with their massive reddish trunks and open, sculptural crowns, are among the most impressive trees in the American West.