Red Elderberry (Sambucus racemosa)

Sambucus racemosa, commonly known as Red Elderberry, stands as one of North America’s most widespread and ecologically important native shrubs. With its distinctive pyramidal clusters of bright red berries and fast growth habit, this adaptable species ranges from coast to coast and provides crucial wildlife food across diverse ecosystems. Unlike its European relative with edible black berries, Red Elderberry produces colorful but toxic red fruits that serve as a vital food source for over 40 species of birds while warning mammals and humans away with their bitter taste and mild toxicity.

This hardy member of the Adoxaceae family (formerly Caprifoliaceae) demonstrates remarkable adaptability, thriving from sea level to subalpine zones across an enormous geographic range that extends from Alaska to New Mexico and from the Pacific Coast to the Atlantic. Red Elderberry typically grows 8 to 15 feet tall, though exceptional specimens can reach 20 feet, forming multi-stemmed colonies through root suckers that make it valuable for naturalizing and erosion control.

What makes Red Elderberry particularly valuable to both ecosystems and gardeners is its exceptional wildlife value combined with ornamental appeal and incredible ease of cultivation. The shrub produces abundant creamy-white flower clusters in late spring that attract numerous pollinators, followed by brilliant red berry clusters that provide crucial food for wildlife during late summer when few other native fruits are available. Its fast growth, shade tolerance, and ability to thrive in moist soils make it an excellent choice for rain gardens, woodland edges, and naturalized landscapes throughout much of North America.

Identification

Red Elderberry is easily recognized by several distinctive characteristics that make it stand out among native shrubs. The plant typically grows 8 to 15 feet tall and 6 to 12 feet wide, developing a somewhat irregular, multi-stemmed growth habit with numerous shoots arising from the base. In optimal conditions, it can reach 20 feet in height, though this is uncommon in most garden settings.

Stems & Bark

Young stems are smooth and green to reddish-brown, becoming gray-brown with age. The most distinctive feature of elderberry stems is the prominent white pith that fills the center of hollow branches — this soft, spongy interior can be easily pushed out with a thin stick, making elderberry stems useful for various craft purposes. Mature bark is grayish-brown with shallow furrows and a somewhat corky texture.

Leaves

The leaves are opposite and pinnately compound, typically consisting of 5 to 7 leaflets arranged along a central rachis. Each leaflet is 2 to 5 inches long, lance-shaped to oval, with serrated margins and a pointed tip. The upper surface is dark green and somewhat glossy, while the underside is paler. In fall, the foliage turns various shades of yellow before dropping, though fall color is often unreliable and the plant may simply drop green leaves after the first hard frost.

Flowers

The flowers appear in late spring to early summer (typically May through July depending on elevation and climate) in large, pyramidal clusters called panicles that can be 3 to 6 inches long. Each individual flower is small, creamy-white to yellowish, with 5 petals and prominent yellow stamens. The flower clusters are densely packed and emit a somewhat musky, sweet fragrance that attracts numerous pollinators. The timing of flowering is particularly valuable, as it occurs when many native pollinators are most active but before many other plants are blooming abundantly.

Fruit

The fruit clusters ripen in late summer to early fall, transforming from green to bright red berries that are ¼ to ⅜ inch in diameter. Unlike the flat-topped flower clusters, the fruit clusters maintain the pyramidal shape, creating attractive cone-shaped displays of brilliant red berries. Each berry contains 3 to 5 small seeds and has a bitter, somewhat astringent taste that makes it unpalatable to humans but attractive to birds. The berries contain compounds that can cause digestive upset in humans and should not be consumed.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Sambucus racemosa L. |

| Family | Adoxaceae (Muskroot) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Shrub |

| Mature Height | 1–8 ft |

| Mature Width | 6–12 ft (1.8–3.6 m) |

| Growth Rate | Fast |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Soil Type | Moist, well-drained; adaptable |

| Soil pH | 5.5–7.5 (slightly acidic to slightly alkaline) |

| Bloom Time | May – July |

| Flower Color | Creamy-white |

| Fall Color | Yellow (variable) |

| Fruit | Bright red berries (toxic to humans) |

| Deer Resistant | No (frequently browsed) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–7 (varies by subspecies) |

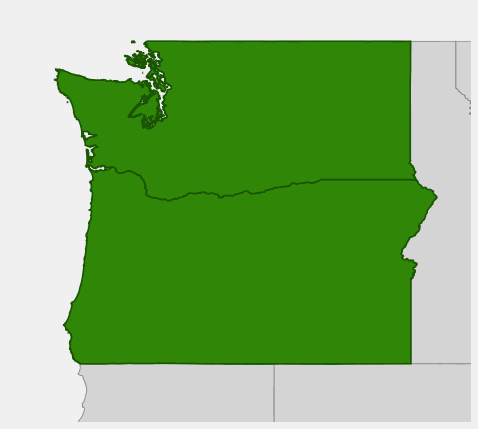

Native Range

Red Elderberry boasts one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American shrub, extending across virtually the entire continent in suitable habitats. The species ranges from Alaska and northern Canada south to Mexico, and from the Pacific Coast to the Atlantic, making it one of the most geographically widespread woody plants in North America. This enormous range reflects the plant’s exceptional adaptability to diverse climatic conditions and elevation ranges.

Within this vast range, Red Elderberry typically occurs in moist, partially shaded habitats including forest edges, stream corridors, avalanche chutes, and disturbed areas. In the Pacific Northwest, it’s common from sea level to elevations of 10,000 feet, growing in everything from coastal fog zones to subalpine meadows. The species shows particular affinity for areas with reliable moisture — stream banks, seeps, north-facing slopes, and forest openings where snow persists longer.

Throughout its range, Red Elderberry often serves as an early successional species, quickly colonizing disturbed areas, clearcuts, and avalanche zones where its fast growth and prolific fruit production help establish wildlife food webs in recovering ecosystems. This pioneering tendency, combined with its extensive root suckering ability, makes it valuable for natural revegetation of disturbed sites.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Red Elderberry: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Red Elderberry ranks among the easiest native shrubs to grow, combining rapid establishment with minimal maintenance requirements and exceptional adaptability to diverse conditions. Its fast growth and forgiving nature make it an excellent choice for beginning native plant gardeners, while its wildlife value and ornamental interest appeal to experienced landscapers.

Light Requirements

This versatile shrub performs well in full sun to partial shade, though it flowers and fruits most abundantly with at least 4-6 hours of direct sunlight daily. In very hot climates, some afternoon shade is beneficial, while in cooler regions it tolerates full sun well. The plant naturally grows in forest edge habitats, making it perfect for transitional zones between sun and shade in the landscape.

Soil & Water Requirements

Red Elderberry thrives in moist, well-draining soil but adapts to a wide range of soil types including clay, loam, and sandy soils. It prefers slightly acidic to neutral soil (pH 5.5-7.0) but tolerates both more acidic and slightly alkaline conditions. The plant has moderate to high water needs and performs best with consistent moisture, especially during the growing season.

While Red Elderberry can tolerate brief dry periods once established, it truly excels in areas with reliable moisture. This makes it excellent for rain gardens, bog edges, and areas with poor drainage where many other shrubs struggle. Mulching around the base helps retain soil moisture and suppress weeds.

Planting & Establishment

Plant Red Elderberry in fall or early spring for best establishment. Space plants 8-10 feet apart for individual specimens, or 6-8 feet apart for informal screening. The shrub transplants easily from containers and establishes quickly, often showing significant growth in the first year. Young plants benefit from regular watering during their first growing season.

Pruning & Maintenance

Red Elderberry requires minimal pruning but benefits from occasional maintenance to keep it looking its best. Prune in late winter or early spring, removing dead, damaged, or crossing branches. The plant flowers on new wood, so spring pruning won’t affect blooming.

For size control or rejuvenation, you can cut the entire shrub back to 12-18 inches from the ground in late winter. The plant responds vigorously to this treatment, quickly regrowing to full size. This technique is particularly useful for overgrown specimens or when you want to maintain a more compact form.

Propagation

Red Elderberry is easily propagated by several methods. The plant naturally produces root suckers, which can be dug and transplanted in spring. Softwood cuttings taken in early summer root readily under mist. Seeds can be collected from ripe berries in fall, cleaned, and cold stratified over winter before spring sowing.

Landscape Uses

Red Elderberry’s versatility and rapid growth make it valuable in numerous landscape applications:

- Wildlife gardens — provides food and nesting sites for diverse species

- Rain gardens & bioswales — thrives in temporarily wet conditions

- Erosion control — root suckers help stabilize slopes

- Screening & privacy — fast growth creates quick natural barriers

- Forest edge plantings — bridges the transition between lawn and woods

- Restoration projects — excellent pioneer species for disturbed sites

- Naturalized areas — forms attractive colonies through suckering

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Red Elderberry stands out as one of the most ecologically valuable native shrubs in North America, supporting an extraordinary diversity of wildlife throughout all seasons. Its combination of flowers, fruit, dense branching structure, and extended geographic range makes it a keystone species in many ecosystems.

For Birds

Over 40 species of birds consume Red Elderberry fruits, making it one of the most important late-summer food sources in many ecosystems. Major consumers include American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Thrushes, Grosbeaks, Finches, and various Sparrow species. Band-tailed Pigeons, Ruffed Grouse, and Sharp-tailed Grouse also eat the berries, while hummingbirds occasionally visit the flowers for nectar.

The dense, multi-stemmed growth habit provides excellent nesting sites for songbirds. The plant’s rapid growth and suckering tendency create thickets that offer thermal cover and protection from predators, making it particularly valuable in areas recovering from disturbance.

For Mammals

While the berries are mildly toxic to humans, they’re consumed by numerous mammals including Black Bears, Chipmunks, Squirrels, and various small rodents. Deer and Elk browse the foliage, though the plant typically recovers well from browsing due to its vigorous growth habit. Moose consume both foliage and twigs, particularly in northern regions where the plant forms extensive colonies.

For Pollinators

The large flower clusters bloom during a critical period when many native pollinators are most active. Native bees, including bumblebees and various solitary species, are frequent visitors, along with beneficial wasps, hover flies, and butterflies. The flowers provide both nectar and pollen, supporting pollinator communities during the late spring to early summer period.

Ecosystem Role

As a pioneer species, Red Elderberry plays a crucial role in ecosystem succession and recovery. It quickly colonizes disturbed areas, helping to stabilize soil and provide the initial wildlife habitat that allows forest regeneration to proceed. The plant’s nitrogen-fixing associations and rapid leaf turnover help build soil organic matter in degraded sites.

In riparian environments, Red Elderberry helps control erosion while its berries provide food for wildlife that disperse seeds of other plants, facilitating forest recovery. The plant’s tendency to form colonies through root suckering creates habitat patches that support diverse communities of birds, mammals, and insects.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Red Elderberry holds significant cultural importance among Indigenous peoples throughout North America, who have utilized this widespread plant for thousands of years. Unlike the European Black Elderberry, Red Elderberry’s fruits are not suitable for human consumption due to their bitter taste and mild toxicity, but the plant provided numerous other valuable uses that demonstrate sophisticated ethnobotanical knowledge.

Among Pacific Northwest tribes including the Chinook, Quinault, and Shuswap, Red Elderberry bark and inner wood were valued for their practical properties. The soft, white pith in the center of stems was easily removed to create hollow tubes used for various purposes — from simple straws for drinking to more complex applications in traditional crafts and tools. Young shoots with the pith removed were used to make whistles and flutes, while the hollow stems served as tubes for blowguns and other implements.

Many Indigenous groups used Red Elderberry medicinally, though specific applications varied among different tribes and regions. The inner bark was sometimes prepared as decoctions for treating various ailments, while the leaves and flowers had specific traditional uses. However, these medicinal applications should never be attempted without proper cultural knowledge and guidance, as the plant contains compounds that can be harmful if improperly prepared.

The wood, though soft, was occasionally used for small carved items and tools. In some regions, the straight young shoots were harvested for arrow shafts and other implements requiring lightweight, straight wood. The plant’s tendency to produce numerous straight shoots made it a renewable resource for these applications.

Early European settlers quickly learned to distinguish Red Elderberry from the familiar Black Elderberry of their homeland, noting that the red berries were not suitable for food preparation. However, they did adopt some Indigenous uses, particularly utilizing the hollow stems for various farm and household purposes. The plant’s rapid growth and colonizing ability made it both useful and sometimes problematic for early agriculture.

In modern times, Red Elderberry has gained recognition as an outstanding native plant for ecological restoration and wildlife landscaping. Its exceptional wildlife value, rapid establishment, and ability to thrive on disturbed sites make it invaluable for revegetating areas damaged by logging, mining, or development. Contemporary ecological restoration projects often feature Red Elderberry as a pioneer species that helps establish the wildlife communities necessary for successful ecosystem recovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Red Elderberry berries poisonous?

Yes, Red Elderberry berries contain compounds that are mildly toxic to humans and can cause digestive upset, nausea, and diarrhea if consumed. However, they are an important and safe food source for birds and wildlife. Always supervise children around the plant and teach them not to eat the attractive red berries.

How fast does Red Elderberry grow?

Red Elderberry is a fast-growing shrub, typically adding 2-4 feet per year under favorable conditions. Young plants can grow even faster during their first few establishment years. This rapid growth makes it excellent for quick screening and wildlife habitat establishment.

Will Red Elderberry take over my garden?

Red Elderberry does spread through root suckers and can form colonies over time. However, the suckers are easy to remove if you want to control its spread. Many gardeners appreciate this tendency as it creates valuable wildlife thickets, but it can be managed through regular removal of unwanted shoots.

When do the berries ripen, and how long do they last?

The berries typically ripen in late summer to early fall (August through October, depending on location). They’re quickly consumed by birds and wildlife, so the colorful display usually lasts only a few weeks. This timing is crucial as it provides food when many other fruit sources are scarce.

Can I grow Red Elderberry from seed?

Yes, Red Elderberry can be grown from seed, though the process requires patience. Collect ripe berries in fall, clean the seeds, and cold stratify them in the refrigerator for 2-4 months. Sow in spring and expect variable germination. The plant also propagates easily from cuttings or by transplanting natural suckers.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Red Elderberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington