Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia)

Amelanchier alnifolia, commonly known as Serviceberry, is one of North America’s most versatile and valuable native shrubs. Also called Saskatoon Berry, Western Serviceberry, and Juneberry, this deciduous member of the rose family combines exceptional beauty with remarkable ecological value. From its prolific white spring blooms that attract early pollinators to its dark purple summer berries beloved by wildlife and humans alike, Serviceberry stands as a cornerstone species across diverse ecosystems from Alaska to New Mexico. The plant’s name derives from the Cree word “misâskwatômina,” while “service berry” reflects European settlers’ comparison to the Old World service trees. Hardy, adaptable, and stunning through all seasons, Serviceberry deserves a place in every native plant garden.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Amelanchier alnifolia |

| Plant Type | Deciduous shrub or small tree |

| Height | 3-26 feet (1-8 meters), rarely to 33 feet |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Soil Type | Adaptable; prefers well-draining soils with organic matter |

| Soil pH | 6.0-7.5 (slightly acidic to slightly alkaline) |

| Bloom Time | April to July (varies by elevation and latitude) |

| Flower Color | Pure white |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2-7 |

Identification

Serviceberry is a variable species that can present as either a multi-stemmed shrub or small single-trunked tree, depending on growing conditions and variety. The plant typically forms colonies through underground suckering, creating thickets of stems ranging from 3 to 26 feet tall, though exceptional specimens can reach 33 feet in optimal conditions.

Leaves

The leaves are perhaps the most reliable identifying feature, being oval to nearly circular in shape and measuring 2-5 cm long by 1-4.5 cm wide. Each leaf sits on a distinct petiole (leaf stem) that measures 0.5-2 cm in length. The leaf margins are serrated, but importantly, the teeth occur only on the upper half to two-thirds of the leaf—the base is always entire (smooth-edged). Leaves emerge with a bronze-green flush in spring, mature to bright green in summer, and transform to brilliant yellow, orange, and red in fall. The specific epithet “alnifolia” means “alder-leafed,” referring to the leaf shape’s resemblance to alder leaves.

Bark

Young stems display smooth, gray bark that becomes slightly furrowed with age on larger trunks. The bark on older specimens can range from gray to reddish-brown, with shallow longitudinal ridges developing over time.

Flowers

The white flowers appear in dense, upright clusters called racemes, typically containing 3-20 individual flowers. Each flower measures 2.5-5 cm across and displays the classic five-petaled rose family structure with five separate white petals, five green sepals, twenty yellow stamens, and five styles. The flowers are notably fragrant and appear before or alongside the emerging leaves, creating a spectacular early-season display that can completely cover the shrub in white.

Fruit

The fruit are small, berry-like pomes measuring 5-15 mm in diameter. They ripen from green through red to dark purple or nearly black, developing a characteristic waxy bloom on the surface. The fruits ripen in early to mid-summer and have a sweet, nutty flavor reminiscent of blueberries with hints of almond. Botanically, they’re pomes (like apples) rather than true berries, containing several small, soft seeds that are completely edible.

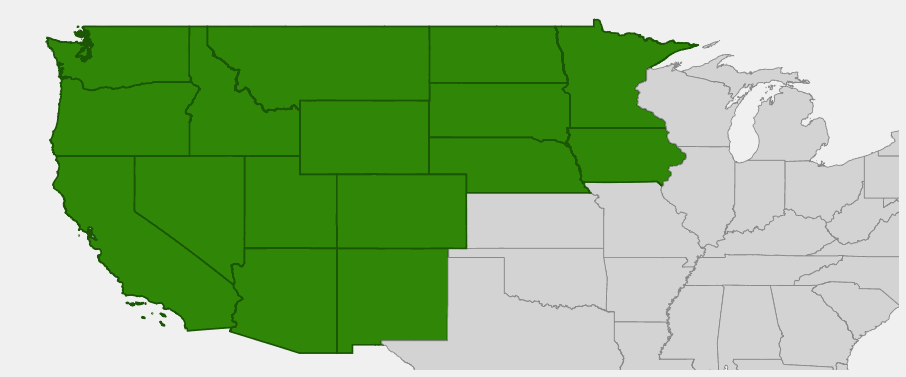

Native Range

Serviceberry boasts one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American shrub, stretching from Alaska south through western and central Canada to northern Mexico, and from the Pacific Coast east to the Great Lakes region and portions of the Great Plains. This remarkable distribution encompasses an extraordinary variety of ecosystems, elevations, and climate zones.

The species displays remarkable adaptability across its range, thriving from coastal sea level environments in the Pacific Northwest to high-elevation rocky slopes in the Rocky Mountains. Three recognized varieties reflect this geographic and ecological diversity: var. alnifolia in the northeastern portions, var. pumila in the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, and var. semiintegrifolia along the Pacific coastal regions. In forest ecosystems, Serviceberry commonly inhabits the understory, forest edges, and openings, while in more open landscapes it colonizes hillsides, canyon slopes, and prairie margins.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Serviceberry: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Serviceberry’s extensive native range hints at its remarkable adaptability in cultivation. This hardy shrub tolerates a wide variety of growing conditions while requiring minimal care once established, making it an excellent choice for both novice and experienced native plant gardeners.

Light Requirements

While Serviceberry can tolerate partial shade (particularly in hot climates), it performs best in full sun where it will produce the most abundant flowers and fruit. In shadier locations, the plant tends to become more open and lanky, though it will still bloom and fruit adequately. Morning sun with afternoon shade can be beneficial in extremely hot, dry regions.

Soil Preferences

Perhaps no other aspect of Serviceberry cultivation demonstrates its adaptability better than its soil tolerance. The species thrives in well-draining loams but readily adapts to sandy soils, clay soils (provided they don’t become waterlogged), and rocky soils with minimal organic matter. pH tolerance is equally broad, with plants succeeding in slightly acidic to slightly alkaline conditions (pH 6.0-7.5). The main soil requirement is drainage—while Serviceberry can handle seasonal flooding, it will not tolerate permanently waterlogged conditions.

Water Requirements

Established Serviceberry plants demonstrate impressive drought tolerance, reflecting their adaptation to diverse climatic conditions across their native range. However, consistent moisture during the first growing season aids establishment. Once roots are developed, plants typically thrive on natural precipitation in most regions, though supplemental irrigation during extended dry periods will promote better fruit production and overall plant vigor.

Planting Tips

Spring planting generally provides the best establishment success, though fall planting can work in milder climates. Space individual plants 4-6 feet apart for screening or hedging applications, or allow 8-12 feet between plants if developing them as specimen trees. The natural suckering habit means plantings will eventually form colonies unless root suckers are regularly removed.

Pruning and Maintenance

Serviceberry requires minimal pruning in naturalized settings. For landscape applications, light pruning in late winter can help maintain shape and remove any dead, damaged, or crossing branches. If developing the plant as a small tree rather than a shrub, early training to select a single trunk and removal of lower branches will be necessary. Suckers can be removed if a single-stemmed form is desired, or allowed to develop for a naturalized colony effect.

Propagation

The species propagates readily through several methods. Root suckers can be carefully separated and transplanted in early spring or fall. Seeds require cold stratification (120 days at 33-41°F) and have variable germination rates. Softwood cuttings taken in early summer root well with rooting hormone treatment, while hardwood cuttings can be taken in late fall.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few native plants match Serviceberry’s ecological importance, supporting an impressive array of wildlife species while serving crucial ecosystem functions across its vast range. From early-season nectar sources to summer fruit production and habitat structure, this species represents a keystone component of healthy native plant communities.

Pollinators

The early blooming period makes Serviceberry flowers a critical nectar and pollen source when few other plants are flowering. Native bees, including mason bees, sweat bees, and mining bees, are primary pollinators, though the flowers also attract beneficial wasps, syrphid flies, and other native insects. Honeybees utilize the flowers when available, but the plant evolved with native pollinators and is most effectively pollinated by indigenous species. The abundant, easily accessible flowers can support large populations of early-season pollinators.

Birds

Serviceberry fruits are among the most important wildlife foods across their range, supporting over 40 bird species. American robins, cedar waxwings, northern flickers, and various thrush species are particularly dependent on the summer fruit crop. The fruit’s high nutritional value—rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and sugars—provides essential energy for breeding birds and migrating species. Many birds time their nesting cycles to coincide with fruit ripening, while others cache fruits for winter consumption.

Mammals

Large mammals including black bears, deer, elk, and moose browse both the foliage and fruit extensively. Small mammals such as chipmunks, squirrels, and various rodent species rely heavily on the fruit, often caching berries for winter food supplies. The dense branching structure provides excellent nesting sites for small mammals and protective cover for larger species.

Lepidoptera

Serviceberry serves as a larval host plant for several butterfly and moth species, including the pale tiger swallowtail, two-tailed swallowtail, and western tiger swallowtail. The leaves support various moth caterpillars, which in turn provide essential protein sources for bird species feeding young. This plant-insect relationship demonstrates the complex food webs that native plants support.

Ecosystem Role

Beyond direct wildlife support, Serviceberry plays important ecological roles in erosion control, soil improvement, and succession dynamics. Its extensive root system stabilizes slopes and stream banks, while the leaf litter contributes organic matter to soil development. In disturbed areas, Serviceberry often serves as a pioneer species, preparing sites for the establishment of other native plants and contributing to ecosystem recovery.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Serviceberry holds one of the most significant places in North American ethnobotany, serving as a crucial food source for Indigenous peoples across the continent for thousands of years. Known by numerous Indigenous names — including Saskatoon (from the Cree misâskwatômina), chokecherry in some regions, and shadberry in others — this plant was so important to many tribes that berry-picking seasons were central events in their annual cycles.

The sweet, nutritious berries were harvested in mid to late summer and processed in various ways for winter storage. Many Plains and Plateau tribes, including the Blackfoot, Crow, and various Salish groups, dried the berries into cakes or mixed them with dried meat and fat to create pemmican — a high-energy food that could sustain people through long journeys and harsh winters. The berries were also ground into flour, made into soups and beverages, or stored in parfleche containers for year-round use.

Beyond food, Indigenous peoples found numerous other uses for Serviceberry. The straight, strong shoots were prized for making arrow shafts, as the wood is both flexible and durable. Various tribes used the inner bark medicinally for treating eye infections, stomach ailments, and as a general tonic, though such uses should never be attempted without proper cultural knowledge and guidance. The wood was also used for tool handles, digging sticks, and other implements requiring strong, resilient material.

Early European explorers and settlers quickly learned the value of Serviceberry from Indigenous peoples. The Lewis and Clark expedition documented extensive use of the berries by Western tribes, and many fur traders and mountain men relied on them as a critical food source. The berries became important to homesteaders as well, who used them fresh, dried, or made into preserves, pies, and beverages.

In modern times, Serviceberry has experienced a renaissance as both a food plant and landscape specimen. Sustainable foragers and wild food enthusiasts prize the berries for their sweet, almond-like flavor and high antioxidant content. The plant has also gained recognition as an outstanding native landscape choice, valued for its four-season interest, wildlife benefits, and remarkable adaptability. Contemporary indigenous communities continue traditional harvesting and preparation methods, maintaining cultural connections that span millennia.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Serviceberry fruits safe to eat?

Yes, Serviceberry fruits are not only safe but delicious and nutritious. They taste sweet with hints of almond and blueberry, and are high in antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals. They can be eaten fresh, dried, or used in baking and preserves. However, like apple seeds, the seeds contain small amounts of cyanogenic compounds, so avoid eating large quantities of seeds.

When do Serviceberries ripen?

Serviceberries typically ripen from mid-June through August, depending on elevation and climate — hence the name “Juneberry” in some regions. The berries turn from red to deep purple-black when fully ripe. They don’t all ripen at once, so you’ll have a harvest period of several weeks.

How can I tell when Serviceberries are ripe?

Ripe Serviceberries are deep purple to nearly black in color and yield slightly to gentle pressure. They should pull easily from the stem when ready. Taste is the best indicator — ripe berries are sweet with a pleasant, mild flavor, while unripe ones are tart and astringent.

Will deer eat my Serviceberry plants?

Yes, deer do browse Serviceberry foliage and twigs, especially in winter. However, the plants typically recover well from browsing due to their vigorous growth habit. In areas with heavy deer pressure, you may want to protect young plants until they’re established, or choose other deer-resistant natives.

Can I grow Serviceberry in containers?

While possible, Serviceberry is challenging to grow long-term in containers due to its size and deep root system. Dwarf varieties or young plants can be grown in large containers temporarily, but for best results and fruiting, plant in the ground where the roots can spread naturally.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Serviceberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington