Thinleaf Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum)

Vaccinium membranaceum, commonly known as Thinleaf Huckleberry, is the crown jewel of North America’s wild berry species. Also called Mountain Huckleberry, Big Huckleberry, and Tall Huckleberry, this remarkable shrub produces some of the most prized wild berries in western North America. Growing in the high-elevation forests and subalpine meadows from Alaska to Arizona, Thinleaf Huckleberry has sustained Indigenous peoples for millennia and continues to be celebrated as Idaho’s official state fruit. The species name “membranaceum” refers to the characteristically thin, almost translucent quality of its leaves, while its large, dark purple berries are legendary among foragers for their exceptional flavor and nutritional value. Fire-adapted and ecologically vital, this hardy heath family member represents the essence of mountain wilderness ecosystems.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Vaccinium membranaceum |

| Plant Type | Deciduous shrub |

| Mature Height | 2–6 ft |

| Height | 1-5 feet (0.3-1.5 meters) |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Soil Type | Well-draining, acidic soils with organic matter |

| Soil pH | 4.5-6.0 (acidic) |

| Bloom Time | May to July (varies by elevation) |

| Flower Color | Pale pink to waxy bronze |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3-7 |

Identification

Thinleaf Huckleberry is a low-growing, erect deciduous shrub that typically reaches 1-5 feet in height, though it can occasionally grow taller in optimal conditions. The plant forms colonies through underground rhizomes, creating patches of interconnected stems that can cover substantial areas of mountain slope.

Leaves

The leaves are the plant’s most distinctive feature, giving rise to both the common and scientific names. These alternately arranged leaves are remarkably thin and membranous, almost translucent when held to light. They measure up to 5 cm (2 inches) long and display an oval shape with finely serrated margins. Each tiny tooth along the leaf edge is tipped with a small glandular hair, creating a characteristic texture when touched. The leaves emerge bright green in spring, deepen to rich green in summer, and transform to spectacular shades of orange, red, and burgundy in fall, often rivaling any maple for autumn color intensity.

Stems and Bark

The newer twigs are particularly distinctive, displaying a yellow-green coloration and somewhat angled or ridged appearance. This square-like twig shape has earned the plant another common name: “square-twig blueberry.” Older stems develop smooth gray-brown bark that may become slightly furrowed with age.

Flowers

The solitary flowers appear in the leaf axils during late spring to early summer, depending on elevation and snowmelt timing. Each flower is about 6 mm (¼ inch) long and displays the characteristic urn-shaped to cylindrical form typical of the heath family. The flowers range from pale pink to a distinctive waxy bronze color, often with a slight greenish tinge. They are pollinated primarily by native bees, which are crucial for fruit production.

Fruit

The berries are truly spectacular—large for a wild huckleberry at about 1 cm (⅜ inch) in diameter, and ranging from deep red through bluish-purple to nearly black when fully ripe. Each fruit contains an average of 47 tiny, soft seeds that are completely edible. The berries ripen from late summer to early fall, turning mountain slopes purple with their abundance in good years. The flavor is intense, sweet-tart, and complex, often described as superior to cultivated blueberries.

Native Range

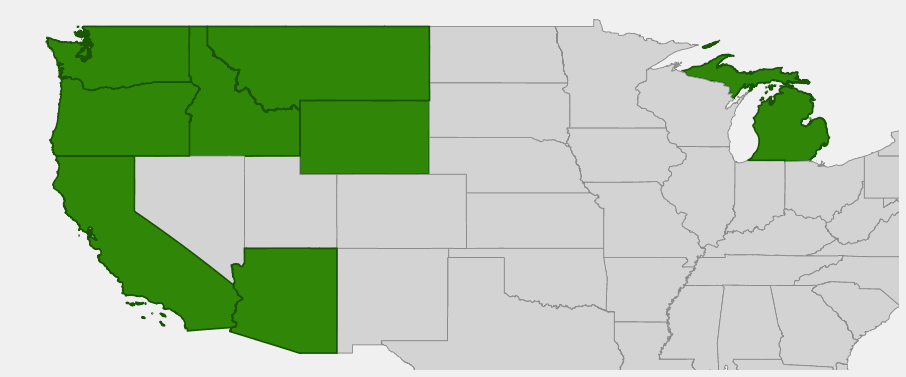

Thinleaf Huckleberry demonstrates one of the most impressive elevational ranges of any North American shrub, thriving from near sea level in northern latitudes to over 10,000 feet elevation in southern mountains. This remarkable distribution reflects the species’ adaptation to cooler climates and shorter growing seasons, whether achieved through latitude or altitude.

The species shows remarkable habitat flexibility within its preferred cool, moist mountain environments. In northern latitudes like Alaska, it grows near sea level in boreal forest understories. Moving south, it climbs ever higher, reaching its elevational limits in the mountains of California, Arizona, and New Mexico. The plant thrives in both dense coniferous forest understories and open mountain meadows, often dominating the shrub layer in early to mid-successional forest stands.

Interestingly, isolated populations exist far from the main range in places like the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and portions of the Black Hills, representing relict populations from cooler climatic periods. These disjunct populations highlight the species’ historical importance and adaptation to post-glacial climate changes.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Thinleaf Huckleberry: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Successfully cultivating Thinleaf Huckleberry requires understanding its mountain origins and specific soil chemistry needs. This species is more challenging to grow than lowland relatives but rewards patient gardeners with exceptional fruit and stunning fall color.

Light Requirements

While Thinleaf Huckleberry tolerates full sun at higher elevations, it generally prefers partial shade, particularly in lower-elevation or warmer gardens. Morning sun with afternoon shade often provides the ideal balance, mimicking the dappled forest light of its native habitat. In very hot climates, more shade may be necessary to prevent stress.

Soil Requirements

Soil chemistry is crucial for success with this species. Thinleaf Huckleberry absolutely requires acidic soil with a pH between 4.5-6.0. The soil must be well-draining yet consistently moist, rich in organic matter, and preferably composed of decomposed forest duff similar to its native mountain soils. Heavy clay soils should be avoided, while sandy loams amended with significant organic matter work well. Adding pine needles, oak leaf mold, or commercial acidic compost can help achieve proper soil conditions.

Water Requirements

Unlike some mountain plants that prefer drought conditions, Thinleaf Huckleberry requires consistent moisture throughout the growing season. The soil should never completely dry out, but waterlogging must also be avoided. Deep, infrequent watering is preferable to frequent shallow irrigation. Mulching with acidic organic matter helps retain moisture and suppress weeds while slowly releasing nutrients.

Climate Considerations

This species requires a significant chill period during winter to break dormancy and produce fruit. Areas with hot summers and mild winters are generally unsuitable. The plant performs best in regions with cool, moist summers and cold winters—essentially trying to recreate mountain climate conditions.

Planting and Establishment

Purchase plants from reputable native plant nurseries, as Thinleaf Huckleberry can be difficult to propagate from seed. Plant in early spring or fall, spacing plants 3-4 feet apart if creating a patch. The shallow root system requires gentle handling during transplanting. A thick mulch of pine needles or shredded bark helps protect the roots and maintain soil acidity.

Maintenance and Pruning

Once established, Thinleaf Huckleberry requires minimal pruning. Remove only dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter. The plant’s natural suckering habit means it will gradually expand to form colonies, which should be encouraged in naturalized settings. In more formal landscapes, suckers can be removed to maintain desired boundaries.

Propagation

The species rarely reproduces from seed in cultivation, preferring vegetative reproduction through rhizomes. Division of established clumps in early spring provides the most reliable propagation method. Softwood cuttings taken in early summer may root with hormone treatment and high humidity, though success rates are variable.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Few plants match Thinleaf Huckleberry’s ecological importance in mountain ecosystems. From providing critical wildlife food to supporting complex forest succession patterns, this species serves as a keystone component of healthy subalpine and montane forest communities.

Large Mammals

The relationship between Thinleaf Huckleberry and bears—both black and grizzly—is legendary throughout the species’ range. Bears consume not only the berries but also leaves, stems, and even roots, with some bears timing their entire annual cycle around huckleberry fruiting seasons. During peak berry production, individual bears may consume thousands of berries daily, gaining crucial fat reserves for winter hibernation. Elk, moose, deer, and mountain goats also heavily browse the plants, particularly the nutritious new growth and berries.

Birds

Over 30 bird species depend on Thinleaf Huckleberry berries as a major food source. Grouse species—including blue grouse, ruffed grouse, and spruce grouse—time their broods to coincide with berry ripening. Thrushes, robins, waxwings, and jays cache berries for winter consumption, while many species use the dense shrub colonies for nesting cover. The plant’s importance to forest bird communities cannot be overstated.

Small Mammals and Insects

The berries support chipmunks, ground squirrels, martens, and numerous other small mammals. The flowers attract native bees, butterflies, and other pollinators during the brief mountain growing season. The dense, low-growing colonies provide essential cover for small mammals during the long mountain winters.

Fire Ecology and Succession

Thinleaf Huckleberry demonstrates remarkable fire adaptation, representing a classic example of how some plants benefit from periodic disturbance. The above-ground portions may be killed by fire, but the extensive rhizome network typically survives underground. Following fire, the plant resprouting vigorously, often achieving higher berry production than before the burn. This response made controlled burning a traditional management tool among Indigenous peoples, who used carefully timed fires to enhance huckleberry production in specific areas.

Cultural and Traditional Uses

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples throughout the plant’s range have depended on Thinleaf Huckleberry as a crucial food source. The berries were eaten fresh, dried for winter storage, mixed into pemmican, and used in traditional medicines. The Kutenai called them “shawíash,” while numerous Pacific Northwest tribes had specific ceremonies and protocols surrounding huckleberry gathering seasons. This cultural relationship continues today, with many Indigenous communities actively managing huckleberry habitat and maintaining traditional harvesting practices.

Modern Commercial Value

Thinleaf Huckleberry remains the most commercially important wild huckleberry species in western North America. Professional foragers and recreational pickers harvest millions of pounds annually, supporting both local economies and cottage industries producing jams, pies, and other products. The berries’ exceptional flavor and limited cultivated production ensure continued demand and premium prices.

Frequently Asked Questions

When are Thinleaf Huckleberries ripe for picking?

Thinleaf Huckleberries typically ripen from late July through September, depending on elevation and weather conditions. Ripe berries are deep blue-black with a waxy bloom and come off the stem easily. They should taste sweet with just a hint of tartness.

Can I grow Thinleaf Huckleberry in my garden?

It’s challenging but possible if you can replicate mountain conditions. The plant needs acidic soil, consistent moisture, cool summers, and cold winter dormancy. Success is most likely in higher elevation gardens with naturally acidic soils and cooler climates.

How can I tell Thinleaf Huckleberry from other huckleberries?

Thinleaf Huckleberry has distinctively thin, delicate leaves (hence the name) that are finely serrated along the edges. The berries are typically larger than other huckleberry species and have a more intense, sweet flavor. The plant also grows taller, often reaching 6 feet or more.

Is it legal to pick huckleberries in national forests?

Generally yes, but regulations vary by location and may require permits for commercial quantities. Always check with local forest service offices for current rules. Personal use quantities (usually a few gallons) are typically allowed, but commercial picking often requires special permits.

Do huckleberries need cross-pollination to produce fruit?

While Thinleaf Huckleberry can self-pollinate to some degree, berry production is much better when multiple plants are present for cross-pollination. In the wild, they often grow in patches, which naturally provides the genetic diversity needed for optimal fruit set.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Thinleaf Huckleberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington

Cultural & Historical Uses

Thinleaf Huckleberry, known as “big huckleberry” or “mountain huckleberry,” holds immense cultural significance for Indigenous peoples of the mountain regions of the Pacific Northwest. The Yakama, Nez Perce, Coeur d’Alene, Spokane, and numerous other tribes considered these berries among the most important traditional foods. The large, sweet, blue-black berries were gathered in late summer during dedicated family expeditions to traditional picking areas in the mountains.

The berries were eaten fresh during the harvest season but were primarily dried for winter storage. Women would spread the berries on special drying racks or mats in the sun, creating a concentrated food source that could last through the winter months. These dried berries were often mixed with dried salmon and fat to create pemmican, a high-energy travel food essential for long journeys and winter survival.

Traditional ecological knowledge surrounding huckleberry management was extensive and sophisticated. Many tribes used controlled burning to maintain productive huckleberry patches, understanding that the plants needed periodic disturbance to remain vigorous and productive. Specific families or clans often had hereditary rights to particular picking areas, and complex protocols governed when and how berries could be harvested to ensure sustainable yields.

The medicinal uses of Thinleaf Huckleberry were also significant. The leaves were brewed into teas to treat diabetes, stomach problems, and various other ailments. Modern research has confirmed that huckleberry leaves contain compounds that can help regulate blood sugar, validating traditional uses. The berries themselves were recognized as important sources of vitamins and antioxidants, essential for maintaining health during long mountain winters.