American Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Tsuga canadensis, commonly known as American Hemlock or Eastern Hemlock, is one of the most graceful and distinctive conifers of eastern North America’s forests. This stately evergreen tree, reaching heights of 40 to 80 feet (occasionally over 100 feet in old-growth stands), has earned a reputation as the “redwood of the East” for its longevity and impressive stature. With its characteristic drooping branches, delicate flat needles, and small pendulous cones, American Hemlock creates a soft, feathery appearance that sets it apart from other conifers in the landscape.

Native to the cool, moist forests of eastern North America from Canada south to northern Georgia and Alabama, American Hemlock thrives in shaded understory conditions where few other large conifers can survive. Its remarkable shade tolerance allows it to dominate the forest floor for decades, slowly growing beneath taller deciduous trees until it eventually emerges to become a canopy dominant. This slow-growing giant can live for several centuries, with some specimens documented to exceed 800 years of age.

Unfortunately, American Hemlock faces severe threats from the invasive hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), an introduced insect that has devastated hemlock populations across much of its range since the 1950s. Despite this challenge, American Hemlock remains an exceptional landscape tree for suitable environments, offering unparalleled wildlife value, year-round evergreen beauty, and a graceful architectural presence that few other native trees can match. Its deep ecological importance and aesthetic appeal make it a treasured species worthy of conservation and cultivation.

Identification

American Hemlock is easily distinguished from other conifers by its combination of small, flat needles arranged in a feathery pattern, drooping branch tips, and tiny cones that hang like teardrops from the branches. Mature trees develop a distinctive pyramidal shape with gracefully weeping branches that create an elegant, layered appearance.

Bark

The bark of young American Hemlocks is smooth and gray-brown, becoming deeply furrowed with age into distinctive scaly ridges. Mature bark is cinnamon-brown to gray-brown in color with broad, flat-topped ridges separated by deep grooves. The bark is relatively thin compared to other large conifers, making the tree vulnerable to fire damage. Inner bark has a reddish-brown color and was historically used for tanning leather due to its high tannin content.

Needles

The needles are the most distinctive feature for identification. They are small (¼ to ¾ inch long), flat, and arranged individually along the twigs in a feathery, two-ranked pattern that creates a flat spray. Each needle is dark green on top with two distinctive white stomatal bands underneath, giving the undersides a silvery-white appearance. The needles are attached to the twig by small petioles (leaf stalks) and tend to curve slightly upward, creating the characteristic soft, feathery texture. Needles persist for 3-6 years before dropping.

Cones & Seeds

American Hemlock produces small, oval seed cones that are ½ to ¾ inch long, hanging singly from branch tips on short stalks. The cones are light brown when mature and hang downward like tiny ornaments. Male pollen cones are small, yellowish, and appear in spring at branch tips. Seeds are small and winged, dispersed by wind when cones open in fall. The tree typically begins producing cones at 15-20 years of age.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Tsuga canadensis |

| Family | Pinaceae (Pine) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen Tree |

| Mature Height | 40–60 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – May |

| Flower Color | Yellowish (pollen cones) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–7 |

Native Range

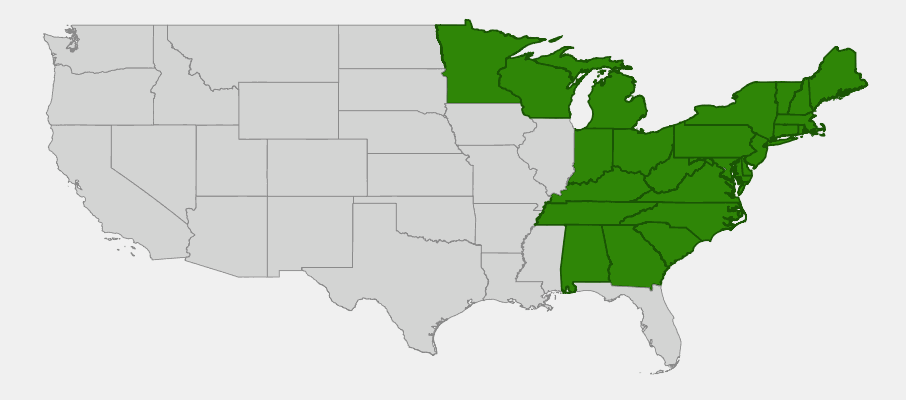

American Hemlock is native to the eastern regions of North America, with its natural range extending from southeastern Canada south through the eastern United States to northern Georgia and Alabama. The species occurs from Nova Scotia west to Minnesota and south along the Appalachian Mountains. In the northern portions of its range, American Hemlock grows from sea level to moderate elevations, while in the southern mountains it is typically found at elevations above 2,000 feet where cooler, moister conditions prevail.

The species thrives in cool, humid climates with well-distributed precipitation throughout the year. It is most abundant in the mixed hardwood-conifer forests of the Great Lakes region, New England, and the Appalachian Mountains. American Hemlock often dominates ravines, north-facing slopes, and other protected sites where it can take advantage of consistent moisture and shelter from extreme temperatures and drying winds.

Historically, American Hemlock was one of the most important timber species in eastern North America, leading to extensive logging that significantly reduced old-growth hemlock forests. Today, the species faces an even greater threat from the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect that has killed millions of hemlocks across the eastern United States. Conservation efforts are underway to preserve remaining populations and develop resistance to this devastating pest.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring American Hemlock: North Carolina & South Carolina

Growing & Care Guide

American Hemlock is a rewarding but challenging tree to grow, requiring specific conditions to thrive. Its exceptional shade tolerance and graceful form make it an outstanding choice for woodland gardens, but successful cultivation requires attention to its needs for cool, moist conditions and protection from environmental stresses.

Light

American Hemlock is famous for its exceptional shade tolerance, able to survive and even thrive in deep shade where most other conifers fail. While it can grow in full sun, it often performs better in partial shade, especially in warmer climates where full sun can stress the tree. In its native range, mature hemlocks often grow as understory trees for decades before reaching the canopy. Young trees in particular benefit from some shade protection during hot summer months.

Soil & Water

American Hemlock prefers well-drained but consistently moist, acidic soils (pH 4.5-6.0) rich in organic matter. The tree is quite sensitive to soil compaction and drought stress. It performs best in cool, humid environments with consistent moisture availability. Sandy loams and loamy soils provide the best growing medium. Avoid planting in heavy clay soils or areas prone to waterlogging. Mulching around the base helps maintain soil moisture and temperature.

Planting Tips

Plant American Hemlock in spring or early fall when temperatures are moderate. Choose a location protected from strong winds and extreme temperature fluctuations. The tree transplants best when young (under 6 feet tall). Space trees at least 20-30 feet apart to allow for mature spread. Consider the eventual size when selecting a planting location, as mature trees can have canopy spreads of 25-35 feet.

Pruning & Maintenance

American Hemlock requires minimal pruning when healthy. Remove any dead, damaged, or crossing branches in late winter or early spring. The tree naturally maintains its pyramidal shape, though lower branches may be removed if desired to create more of a tree form versus shrub form. Avoid heavy pruning, as hemlocks are slow to recover from major cuts. Monitor regularly for signs of hemlock woolly adelgid (white, woolly masses on twigs) and treat promptly if detected.

Landscape Uses

American Hemlock serves multiple landscape functions:

- Specimen tree — elegant focal point with year-round interest

- Privacy screening — dense evergreen foliage provides excellent screening

- Woodland gardens — exceptional shade tolerance for understory planting

- Naturalistic landscapes — authentic native forest feel

- Windbreak or shelterbelt — effective wind protection when planted in groups

- Erosion control — dense root system stabilizes slopes

- Foundation planting — slow growth makes it manageable near buildings (with adequate space)

Wildlife & Ecological Value

American Hemlock is one of the most ecologically important trees in eastern North American forests, providing critical habitat and food resources for numerous wildlife species. Its dense, evergreen canopy creates unique microclimates that support diverse communities of plants and animals.

For Birds

Over 90 bird species use American Hemlock for nesting, roosting, or feeding. The dense branching structure provides excellent nesting sites for species like Dark-eyed Juncos, Golden-crowned Kinglets, and various warblers. Seeds are eaten by Pine Siskins, American Goldfinches, and crossbills. The tree’s evergreen nature provides crucial winter shelter and thermal protection for many bird species, making hemlock groves essential winter habitat in northern climates.

For Mammals

White-tailed Deer rely heavily on hemlock groves for winter shelter and browse, though heavy deer browsing can prevent hemlock regeneration. Snowshoe Hares, Porcupines, and Red Squirrels feed on hemlock needles and bark. Small mammals like shrews, voles, and mice benefit from the stable microclimate beneath hemlock canopies. Black Bears occasionally use large hollow hemlocks for winter denning.

For Pollinators

While American Hemlock is wind-pollinated and doesn’t rely on insect pollinators, the tree supports numerous insects that are important food sources for birds and other wildlife. Over 400 species of butterflies and moths have been documented on American Hemlock, along with various beetles, aphids, and other arthropods that form the base of forest food webs.

Ecosystem Role

American Hemlock functions as a “foundation species” in many eastern forests, fundamentally shaping the structure and function of entire ecosystems. Hemlock groves create cooler, moister microclimates that support specialized plant communities, including rare understory species. The trees’ dense shade suppresses competing vegetation, creating park-like understories. Fallen hemlock needles create acidic soil conditions that favor specialized plant communities. The loss of hemlocks to hemlock woolly adelgid represents one of the most significant ecological disruptions in eastern North American forests today.

Cultural & Historical Uses

American Hemlock has played a significant role in North American history and culture, serving as both a vital natural resource and an important part of regional identity. The tree’s name derives from the superficial resemblance of its crushed foliage’s scent to that of poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), though the two species are completely unrelated and American Hemlock is not poisonous.

Indigenous peoples of eastern North America utilized American Hemlock in numerous ways. The Menominee people used hemlock bark to treat kidney problems and dysentery, while the Potawatomi made a tea from the inner bark to treat kidney and lung ailments. The Ojibwe used hemlock bark as a source of red dye for coloring porcupine quills and other materials. Many tribes collected the vitamin C-rich young tips of hemlock branches to make teas that helped prevent scurvy during long winters.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, American Hemlock was one of the most economically important trees in eastern North America. The bark was the primary source of tannins for the leather industry, leading to extensive harvesting throughout the tree’s range. Massive hemlock forests were clearcut solely for their bark, with the valuable timber often left to rot. By 1900, most old-growth hemlock forests had been eliminated. The wood itself was used for construction lumber, railroad ties, and paper pulp. Hemlock lumber, while not as strong as pine or oak, was prized for its workability and resistance to splitting.

Today, American Hemlock remains culturally significant as a symbol of ancient forests and wilderness. It is the state tree of Pennsylvania and appears on that state’s quarter. The tree features prominently in the writings of naturalists like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, who celebrated its role in creating the cathedral-like atmosphere of old-growth forests. Conservation efforts to save hemlock forests from the hemlock woolly adelgid have brought communities together in recognition of the tree’s irreplaceable ecological and cultural value.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is American Hemlock the same as the poison hemlock that killed Socrates?

No, they are completely different plants. American Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) is a harmless evergreen tree in the pine family, while poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) is a toxic herbaceous plant in the carrot family. The name confusion arose because early European settlers thought the tree’s crushed foliage smelled similar to poison hemlock.

Can American Hemlock survive the hemlock woolly adelgid?

While most American Hemlocks are highly susceptible to hemlock woolly adelgid, some trees show natural resistance or tolerance. Research is ongoing to develop resistant varieties and treatment methods. Early detection and treatment with horticultural oil or systemic insecticides can help protect valuable specimen trees.

How fast does American Hemlock grow?

American Hemlock is a slow-growing tree, typically adding 12-18 inches per year under optimal conditions. Young trees may grow more slowly, especially in heavy shade. The tree’s longevity (300-800+ years) compensates for its slow growth rate, making it a long-term investment in the landscape.

Can American Hemlock grow in warm climates?

American Hemlock is adapted to cool, humid climates and generally doesn’t perform well in hot, dry conditions. It rarely thrives south of USDA Zone 7, though it can sometimes succeed in cooler microclimates within warmer zones, such as north-facing slopes or areas with consistent moisture.

Is American Hemlock drought tolerant?

No, American Hemlock is not drought tolerant and requires consistent soil moisture to thrive. The tree is particularly sensitive to drought stress, which makes it more susceptible to pest problems and can lead to needle drop and branch dieback. Regular watering during dry periods is essential for landscape trees.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries American Hemlock?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Carolina · South Carolina