Climbing Bittersweet (Celastrus scandens)

Celastrus scandens, commonly known as Climbing Bittersweet, American Bittersweet, or Staff Vine, is a vigorous native deciduous vine that creates one of the most spectacular autumn displays in North American woodlands. This member of the Celastraceae (staff-tree) family gets its common name from its climbing habit and the bitter taste of its bark and leaves. The species epithet “scandens” means “climbing,” perfectly describing this vine’s ability to spiral up trees and shrubs to reach heights of 15 to 20 feet or more.

Climbing Bittersweet is renowned for its stunning autumn fruit display, when clusters of bright orange berries split open to reveal brilliant yellow arils (seed coverings) that persist well into winter. This dramatic color combination of orange capsules and yellow arils makes the vine a favorite for autumn decorations and holiday arrangements, earning it significant commercial value in the floral trade. The vine’s twining stems can girdle and eventually kill trees when allowed to grow unchecked, but when properly managed, it provides exceptional ornamental value and wildlife benefits.

As one of the most important native woody vines in eastern North America, Climbing Bittersweet plays a crucial ecological role in forest edge and woodland communities. Its berries provide vital winter food for numerous bird species, while its dense growth offers nesting sites and cover. The vine is particularly valuable for wildlife because it retains its colorful fruits through much of the winter when other food sources become scarce. For gardeners and restoration practitioners, this adaptable climber offers excellent potential for naturalistic landscapes, provided it is given appropriate support and management.

Identification

Climbing Bittersweet is a vigorous deciduous woody vine that typically reaches 15 to 20 feet in length, though it can grow much longer in favorable conditions. The vine climbs by twining its stems in a counter-clockwise direction around supports, using no tendrils or aerial rootlets. The young stems are green to reddish-brown and become increasingly woody with age, developing a light brown to grayish bark with prominent lenticels.

Stems & Growth Habit

The stems are slender, flexible, and distinctly twining, wrapping around supports in a spiraling pattern. Young growth is green to reddish, becoming brown and woody with age. The bark develops light-colored horizontal lines (lenticels) that are quite prominent on older stems. Unlike some climbing vines, Climbing Bittersweet does not produce tendrils, adhesive discs, or aerial roots — it climbs purely by twining its stems around available supports.

Leaves

The leaves are simple, alternate, and oval to oblong in shape, measuring 2 to 4 inches long and 1 to 2 inches wide. They have a pointed tip and finely serrated (toothed) margins. The leaves are bright to medium green during the growing season, turning yellow to yellow-orange in fall before dropping. The leaf surfaces are smooth (glabrous) on both sides, and the petioles (leaf stalks) are typically ½ to 1 inch long.

Flowers

The flowers are small, greenish-yellow, and relatively inconspicuous, appearing in late spring to early summer (May-June). They are arranged in small terminal clusters (panicles) at the ends of branches. Climbing Bittersweet is dioecious, meaning individual plants are either male or female, so both sexes are needed for fruit production. The flowers have five petals and are about ⅛ to ¼ inch across.

Fruit

The fruit is the most distinctive and ornamentally valuable feature of Climbing Bittersweet. The berries are round capsules, about ⅓ to ½ inch in diameter, that start green and mature to bright orange or orange-red in fall. When ripe, the three-lobed capsules split open to reveal 1 to 3 bright yellow or orange-red arils (seed coverings) that completely enclose the seeds. This spectacular color combination of orange capsules and brilliant yellow-orange arils creates one of the most striking autumn displays of any native vine. The fruits persist on the vine well into winter, providing both ornamental value and wildlife food.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Celastrus scandens |

| Family | Celastraceae (Staff-tree) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Woody Vine |

| Mature Height | 15–20 ft vine |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – June |

| Flower Color | Greenish-yellow |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–8 |

Native Range

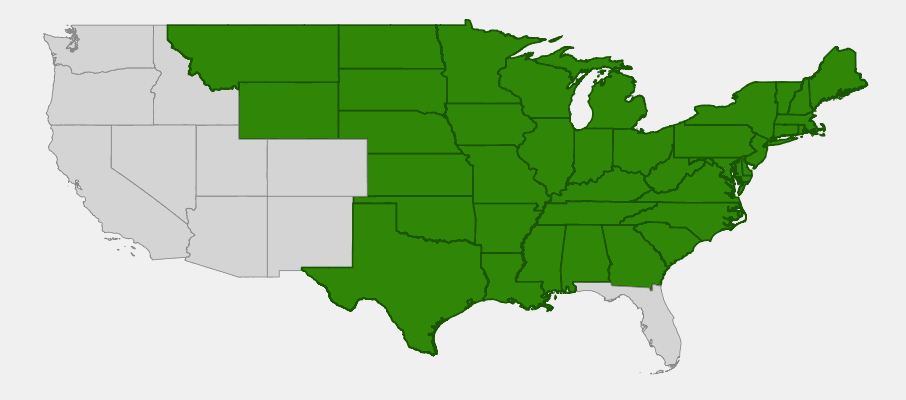

Climbing Bittersweet has an extensive native range across eastern and central North America, occurring from southeastern Canada south to Georgia and west to Montana and New Mexico. The species is most common throughout the eastern United States, where it typically grows in forest edges, woodland openings, and along stream corridors. Its range extends from the Atlantic Coast west to the Great Plains, with scattered populations in the Rocky Mountain region.

The vine is particularly abundant in the mixed hardwood forests of the eastern United States, where it commonly occurs along forest margins, in clearings, and in areas with partial canopy cover. It thrives in the transition zones between forest and open areas, often colonizing fence rows, woodland edges, and disturbed sites where it can find adequate light and support structures. The species shows remarkable adaptability to different soil types and moisture conditions across its broad range.

Westward, Climbing Bittersweet becomes less common but still occurs in suitable habitats, particularly along streams and in protected valleys where moisture and support structures are available. In the northern portions of its range, it often grows in association with other native vines and woodland edge species, while in the south it may be found in bottomland forests and along creek banks where it can climb into the forest canopy.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Climbing Bittersweet: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Climbing Bittersweet is a relatively easy native vine to grow, offering exceptional ornamental value with minimal maintenance requirements. However, its vigorous growth habit requires careful management to prevent it from overwhelming other plants in the landscape.

Light

This adaptable vine thrives in full sun to part shade conditions, though fruiting is typically best in locations that receive at least 6 hours of direct sunlight daily. In full sun, the vine produces the most abundant flowering and fruiting, along with the best autumn color. In partial shade, it will still grow vigorously but may produce fewer flowers and fruits. The vine can tolerate fairly deep shade, making it useful for woodland gardens, though flowering will be reduced in very shady locations.

Soil & Water

Climbing Bittersweet is quite tolerant of various soil conditions, thriving in everything from sandy loam to clay soils. It prefers well-drained soils but can tolerate occasional flooding as well as moderate drought conditions once established. The vine performs best in soils with a pH range of 6.0–7.5 (slightly acidic to slightly alkaline) and benefits from organic matter incorporation, though this is not essential for success.

Water needs are moderate — the vine requires regular water during establishment but becomes quite drought tolerant once the root system is developed. It performs well in areas that receive natural rainfall but may benefit from supplemental watering during extended dry periods, especially if grown in containers or very sandy soils.

Planting Tips

Plant Climbing Bittersweet in spring or early fall when root establishment can occur before temperature extremes. Choose a location with sturdy support structures such as arbors, pergolas, or strong fence posts — avoid planting near small trees or shrubs that could be damaged by the vine’s vigorous growth. Since the species is dioecious (separate male and female plants), plant at least one male plant for every 3-4 female plants to ensure good fruit production.

Space plants 6–10 feet apart if creating a screen or covering a large structure. The vine can also be grown in large containers with appropriate support, though it will require more frequent watering and fertilization in this situation.

Pruning & Maintenance

Regular pruning is essential to keep Climbing Bittersweet under control and prevent it from becoming invasive in the landscape. Prune in late winter or early spring before new growth begins, removing any weak or dead stems and cutting back vigorous growth to maintain the desired size and shape. The vine responds well to hard pruning if it becomes overgrown.

Monitor the vine regularly during the growing season and remove any stems that are beginning to girdle or damage support trees or structures. The vine’s twining habit can eventually kill small trees if left unchecked, so management is crucial in mixed plantings.

Landscape Uses

Climbing Bittersweet excels in multiple landscape applications:

- Ornamental screening — excellent for covering unsightly structures or creating privacy

- Autumn decoration — provides cut stems for fall and winter arrangements

- Wildlife gardens — critical winter food source for birds

- Woodland edges — naturalizes well in forest transition areas

- Pergolas and arbors — creates attractive seasonal displays on garden structures

- Erosion control — useful for stabilizing slopes and banks where other plants struggle

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Climbing Bittersweet provides exceptional ecological value, supporting wildlife throughout the year with food, shelter, and nesting sites. Its significance is particularly pronounced during autumn and winter when many other food sources become scarce.

For Birds

The bright orange berries with their yellow arils are consumed by over 15 species of birds, making Climbing Bittersweet one of the most important native food sources for winter bird survival. American Robins, Cedar Waxwings, Northern Mockingbirds, Blue Jays, and various woodpecker species regularly feed on the fruits. The berries are particularly valuable because they persist on the vine through much of the winter, providing food when insects and other resources are unavailable. The dense twining growth also provides excellent nesting sites and protective cover for small songbirds.

For Mammals

Small mammals including squirrels, chipmunks, and mice consume the seeds and occasionally the berries. The dense vine growth creates protective cover and travel corridors for small mammals, while the fibrous bark has historically been used by some mammals for nest building. White-tailed deer occasionally browse the foliage, particularly young shoots in spring, though the bitter taste typically limits heavy browsing.

For Pollinators

Although the flowers are small and inconspicuous, they attract various small insects including native bees, flies, and beetles during the late spring blooming period. These pollinators are essential for fruit production, and the vine’s flowers provide nectar and pollen resources during a time when many other native plants are not yet blooming.

Ecosystem Role

As a native woody vine, Climbing Bittersweet contributes to vertical habitat structure in forest edge and woodland communities. Its climbing habit allows it to create layered vegetation that supports different wildlife species at various heights. The vine also helps stabilize soil on slopes and banks through its extensive root system, while its seasonal leaf drop contributes organic matter to forest floor ecosystems. In natural settings, the vine creates important habitat connectivity, allowing wildlife to move between different forest layers and edge habitats.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Climbing Bittersweet has a rich history of human use throughout its native range, serving both practical and cultural purposes for Indigenous peoples and later European settlers. Various Native American tribes made extensive use of the vine, recognizing its value for both material and medicinal applications.

The strong, flexible stems were used by Indigenous peoples for basketry, binding, and cordage. The fibrous inner bark could be processed into rope or twine, while the woody stems were sometimes used in construction of temporary shelters or fish traps. Some tribes used the bark medicinally, though the plant’s bitter compounds meant it was typically reserved for specific ailments and used with caution.

European settlers quickly adopted the use of Climbing Bittersweet for decorative purposes, particularly valuing the spectacular autumn fruit displays for home decoration and holiday arrangements. The vine became a popular element in colonial and early American interior design, with the colorful berries used in wreaths, swags, and centerpieces. This decorative tradition continues today, with Climbing Bittersweet being commercially harvested for the floral trade.

Unfortunately, commercial harvesting pressure, combined with habitat loss, has led to significant declines in wild populations of Climbing Bittersweet in many areas. The situation has been further complicated by the introduction and spread of Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), an invasive Asian species that outcompetes the native vine and hybridizes with it. This has led to conservation concerns and efforts to protect remaining native populations.

In modern landscaping and ecological restoration, Climbing Bittersweet has gained renewed appreciation for its wildlife value and ornamental qualities. Many native plant enthusiasts and restoration practitioners now specifically seek out true native Climbing Bittersweet to support bird populations and maintain genetic integrity of local ecosystems. The vine has become a symbol of the importance of choosing native species over non-native alternatives in landscape design.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell native Climbing Bittersweet from invasive Oriental Bittersweet?

Native Climbing Bittersweet has fruits clustered at the ends of branches, while Oriental Bittersweet has fruits scattered along the stems. Native bittersweet leaves are more pointed and have finer teeth along the edges, while Oriental bittersweet has rounder leaves with coarser teeth. The invasive species also tends to be more aggressive and forms denser infestations.

Do I need both male and female plants to get berries?

Yes, Climbing Bittersweet is dioecious, meaning individual plants are either male or female. You need at least one male plant to pollinate every 3-4 female plants for good fruit production. Unfortunately, you often can’t tell the sex of a plant until it flowers, so purchasing from a reputable native plant supplier is recommended.

Will Climbing Bittersweet damage my trees?

Yes, if left unmanaged. The vine can eventually girdle and kill trees, especially smaller ones, by wrapping tightly around the trunk and restricting growth. Regular monitoring and pruning can prevent this problem. Provide alternative support structures like sturdy posts or pergolas instead of relying solely on living trees.

When should I harvest the berries for decorations?

Harvest when the orange capsules are fully colored but before they split open to show the yellow arils — usually in early to mid-fall. Cut stems in the morning when they’re fully hydrated, and place in water immediately. The berries will continue to open indoors and can last for months in arrangements if kept cool and dry.

Is Climbing Bittersweet invasive or aggressive?

The native species can be vigorous but is not typically invasive in the way that Oriental Bittersweet is. However, it does require management to prevent it from overwhelming other plants. With proper pruning and monitoring, native Climbing Bittersweet is a well-behaved garden plant that provides exceptional wildlife value.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Climbing Bittersweet?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota