Big Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata)

Artemisia tridentata, commonly known as Big Sagebrush, is the most iconic and ecologically significant shrub of the American West. Silvery-gray, strongly aromatic, and astonishingly resilient, it blankets more than 150 million acres of the Intermountain West — from the high desert basins of the Great Basin to the rolling foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Its pungent, medicinal fragrance, released when rain falls on the leaves or when a branch is crushed, is one of the most evocative scents in all of North American nature: the unmistakable smell of the West itself.

As a keystone species, Big Sagebrush supports an entire ecosystem. The Greater Sage-grouse depends almost exclusively on sagebrush for winter food and year-round cover. Pronghorn antelope, mule deer, and elk rely on it for forage during harsh winters when other food sources vanish. Hundreds of species of insects — including dozens of native bee species found nowhere else — complete part or all of their life cycles in and around sagebrush shrubs. Even the soil beneath a sagebrush community is fundamentally different from bare ground, enriched by biological soil crusts and mycorrhizal networks that only flourish in intact, undisturbed sagebrush habitat.

For native plant gardeners and habitat restorationists working in the Intermountain West, Big Sagebrush is not merely a good choice — it is often the correct choice. No other single species does more to establish the ecological foundation of western shrubland habitat, and no other shrub is more synonymous with the beauty and character of the arid West. Growing Big Sagebrush in your landscape means participating in the conservation of one of North America’s most threatened ecosystems, the sagebrush steppe.

Identification

Big Sagebrush is a woody, evergreen to semi-evergreen shrub that grows 3 to 12 feet tall, depending on soil depth, moisture, and elevation. The shrub has a rounded, many-branched crown and a woody base with fibrous, shredding bark. In favorable sites with deep soils, individuals can grow impressively large; in shallow, rocky soils or at high elevations, plants remain compact and low-growing. Growth form is strongly influenced by local conditions.

Leaves

The leaves are the plant’s most recognizable feature: small — just 1/2 to 1 inch long — wedge-shaped, and tipped with three characteristic lobes at the apex, giving the species its name (tridentata = three-toothed). The leaf surface is covered with dense silvery hairs that give the plant its distinctive gray-green color and reflect intense desert sunlight. When crushed or wetted, leaves release an intensely aromatic, camphorous scent from numerous oil glands embedded in the leaf tissue. The retained leaves provide critical winter nutrition for wildlife.

Flowers & Seeds

Big Sagebrush blooms in late summer to autumn — typically August through October — producing dense, elongated panicles of small, tubular yellow flowers crowded at the tips of the branches. The flowers are wind-pollinated and individually inconspicuous, but the mass of blooming branches gives the shrub a soft, feathery appearance in fall. The tiny seeds (achenes) ripen in late autumn and are distributed by wind. Sagebrush produces enormous quantities of pollen, which triggers allergies in sensitive individuals during bloom season.

Bark & Stems

Older stems are clothed in shredding, fibrous bark — gray-brown in color, peeling in thin strips to reveal a woody core beneath. The plant’s architecture consists of numerous ascending branches arising from a woody crown, giving it a rounded, billowing form. Young stems are silvery-hairy; older ones become smooth and woody with age. The stems are aromatic when broken and the aromatic oils provide some protection from browsing animals. Several recognized subspecies exist: Basin Big Sagebrush (ssp. tridentata), Mountain Big Sagebrush (ssp. vaseyana), and Wyoming Big Sagebrush (ssp. wyomingensis), each occupying distinct ecological niches within the overall range.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Artemisia tridentata |

| Family | Asteraceae (Daisy) |

| Plant Type | Evergreen to Semi-evergreen Shrub |

| Mature Height | 3–12 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | August – October |

| Flower Color | Yellow (inconspicuous, fall) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 4–8 |

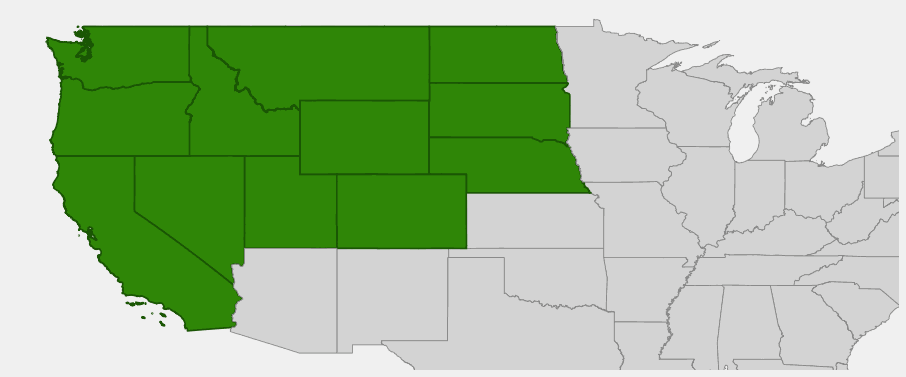

Native Range

Big Sagebrush is native to the western United States and portions of Canada, spanning an enormous range from eastern Washington and Oregon south through the Great Basin of Nevada, Utah, and Idaho, east through Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, and the Dakotas, and into the arid grasslands of Nebraska. It is the dominant shrub of the Great Basin Desert and sagebrush steppe — the largest shrubland ecosystem in North America — covering approximately 150 to 175 million acres in total extent.

Within this vast range, Big Sagebrush occurs across an impressive elevation gradient — from valley floors near sea level in the Great Basin to subalpine zones at 9,000 to 10,000 feet in the Rocky Mountains. It grows in a wide variety of soils, from deep sandy desert loams to gravelly slopes and clay-heavy hardpans, but consistently requires well-drained conditions. It is rarely found in wetlands, floodplains, or areas with persistent standing water. The species defines the open, silvery sea-of-gray panoramas that are the quintessential visual of the interior American West.

Historically, sagebrush country covered much more ground than it does today. Overgrazing, dryland farming conversion, invasive grasses (especially cheatgrass, Bromus tectorum), and fire have drastically reduced sagebrush acreage. Conservation of existing intact sagebrush stands and active restoration of degraded sagebrush habitat are conservation priorities recognized at the federal level. Planting Big Sagebrush is an act of ecological restoration even in the garden context.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Big Sagebrush: Intermountain West

Growing & Care Guide

Big Sagebrush is one of the most adaptable and drought-hardy shrubs for western landscapes. Once established, it thrives with minimal care and is a superb choice for water-wise gardening, wildlife gardens, and habitat restoration in arid and semi-arid climates.

Light

Big Sagebrush requires full sun. It is not tolerant of shade and will not thrive beneath tree canopies or in the shadow of buildings. In its native range, it grows in open, exposed sites that receive maximum sunlight throughout the day. Planting in full sun is essential for healthy growth, fragrant foliage production, and successful long-term establishment.

Soil & Water

Well-drained soil is the single most important cultural requirement. Big Sagebrush is killed by standing water or poorly drained clay soils that promote root rot. It thrives in sandy, gravelly, or loamy soils with a neutral to slightly alkaline pH (6.5–8.5). Once established after 1–2 years, it requires no supplemental irrigation in most western climates. During establishment, water deeply every 2–3 weeks in the absence of rain. Avoid overwatering at all costs — Big Sagebrush in constantly wet soil is a dead Big Sagebrush.

Planting Tips

Plant from container stock in fall or very early spring. Dig a hole no deeper than the root ball and twice as wide. Avoid fertilizer entirely; sagebrush thrives in low-nutrient soils. Mulch with gravel rather than organic mulch to mimic natural conditions and prevent crown rot. Space plants 4–8 feet apart depending on desired density and the subspecies being used. Basin Big Sagebrush grows largest; Wyoming Big Sagebrush stays more compact and is often preferred for garden settings.

Pruning & Maintenance

Big Sagebrush requires almost no pruning under normal conditions. Occasional light shaping in late winter can help maintain a tidy appearance or control size. Avoid cutting back into old wood, as the plant does not regenerate well from severely pruned woody stems. Old, very large shrubs can be replaced with new container stock rather than attempting heavy rejuvenation pruning. The plant is naturally pest- and disease-resistant when grown with good drainage and appropriate air circulation.

Landscape Uses

- Xeriscape foundation plantings — forms a dramatic silvery backdrop for other native plants

- Habitat restoration — the keystone of sagebrush steppe ecosystem restoration projects

- Wildlife gardens — essential for Greater Sage-grouse, pronghorn, mule deer, and specialist insects

- Erosion control on dry slopes and banks where other plants fail

- Windbreaks and screens in arid and semi-arid regions

- Fragrance gardens — aromatic leaves provide year-round sensory interest

- Naturalized meadows with native bunchgrasses, wildflowers, and rabbitbrush

Fire Ecology

Big Sagebrush is highly flammable and does not resprout after fire — it must reestablish from seed. Mature sagebrush communities typically require 50 to 200 years to fully recover after fire. Increased fire frequency driven by invasive cheatgrass is preventing sagebrush recovery and driving conversion of sagebrush steppe to cheatgrass monocultures. For this reason, mature sagebrush stands are considered irreplaceable conservation resources requiring careful fire management.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Big Sagebrush is one of the most ecologically important plants in all of North America. The health of the entire sagebrush ecosystem — from soil microbes to large mammals — is directly tied to the presence and abundance of this single species. Its keystone role makes it essential for conservation-oriented native plant gardeners.

For Birds

The Greater Sage-grouse is the most iconic sagebrush-dependent bird: it feeds almost exclusively on sagebrush leaves in winter, uses tall sagebrush for its remarkable lekking (courtship) displays, and nests beneath sagebrush canopies. Sagebrush-obligate birds also include Sage Sparrow, Sage Thrasher, Brewer’s Sparrow, and Sagebrush Sparrow — all species with populations in serious decline due to sagebrush habitat loss. Many raptors including Golden Eagles, Ferruginous Hawks, and Prairie Falcons hunt over sagebrush landscapes and use tall plants as hunting perches.

For Mammals

Pronghorn antelope rely heavily on sagebrush for winter browse and use it as thermal cover throughout the year. Mule deer and elk are significant consumers of sagebrush foliage in fall and winter when other food is scarce. Pygmy Rabbits (Brachylagus idahoensis) — the world’s smallest rabbit — are almost completely dependent on dense sagebrush: they live in burrows beneath sagebrush canopy and eat almost nothing else in winter. Ground squirrels, jackrabbits, badgers, coyotes, and numerous smaller mammals also inhabit sagebrush ecosystems.

For Pollinators

Although sagebrush flowers are wind-pollinated, the plant supports dozens of native bee species that collect the pollen, including several specialist (Andrena) bees found almost nowhere else. The abundant invertebrate life associated with sagebrush — caterpillars, beetles, true bugs, flies — forms the base of the food chain supporting insectivorous birds, lizards, and other wildlife throughout the growing season.

Ecosystem Role

Beyond wildlife habitat, Big Sagebrush plays a critical role in ecosystem function. Its deep roots stabilize soil against wind and water erosion. Its leaf litter contributes organic matter to naturally nutrient-poor soils. The shrub canopy creates microclimates — cooler, moister conditions beneath the canopy than in open areas — that allow native bunchgrasses, wildflowers, and soil organisms to survive harsh desert conditions. The biological soil crust that forms beneath and around sagebrush is essential to soil fertility and moisture retention.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Big Sagebrush has been central to the lives of Indigenous peoples across the western United States for thousands of years. The Shoshone, Paiute, Navajo, and many other Great Basin and Plateau peoples used virtually every part of the plant. The aromatic leaves were burned as incense and used in purification ceremonies. Bundles of sagebrush were used as brooms, bedding, and insulation in shelters. The bark — fine, shredding, and incredibly soft when processed — was twisted into cordage, woven into baskets, and used as tinder for fire-starting. Sagebrush bark clothing, including moccasins and robes, provided insulation in cold desert winters long before trade with neighboring peoples brought other materials.

Medicinally, sagebrush held a central place in western Indigenous pharmacopoeias. A tea made from the leaves was used to treat colds, fever, digestive complaints, and pain. The leaves were applied directly to wounds, burns, and sore muscles as a poultice. Steam from boiling sagebrush was inhaled for respiratory complaints. The strong antiseptic properties of sagebrush’s volatile oils — particularly camphor, cineole, and other terpenoids — likely gave real medicinal benefit, and modern research has confirmed antimicrobial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties for these compounds. Contemporary pharmaceutical research continues to investigate the bioactive compounds of Artemisia species worldwide.

Ecologically, sagebrush was the centerpiece of the landscapes that sustained entire cultures. The Great Basin peoples organized their seasonal movements around the rhythms of the sagebrush ecosystem. The loss of sagebrush habitat due to overgrazing, fire, and development has been a cultural as well as ecological loss for communities whose spiritual and practical connections to this landscape span millennia. Today, numerous tribes and conservation organizations are partnering on sagebrush restoration projects that serve both conservation and cultural revitalization goals, representing a new synthesis of traditional ecological knowledge and modern restoration science.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does sagebrush smell so strong after rain?

The leaves contain numerous volatile oils — camphor, cineole, and other aromatic compounds — stored in microscopic glands embedded in the leaf surface. When rain falls, it volatilizes these oils and carries them into the air, creating the intensely aromatic cloud that many westerners consider the most beautiful scent in nature. Crushing the leaves produces the same effect year-round.

Is Big Sagebrush difficult to establish?

The biggest challenge is drainage. If your soil drains well and you plant in spring or fall with moderate watering during the first season, sagebrush establishes reliably. Avoid heavy clay soils and overwatering at all costs. Once established after 1–2 years, it needs almost no attention and will thrive for decades.

Can I grow Big Sagebrush with other plants?

Yes, but choose compatible drought-tolerant western natives. Excellent partners include Antelope Bitterbrush, Rubber Rabbitbrush, Bluebunch Wheatgrass, Prairie Junegrass, Lupines, and Penstemons. Avoid mixing with plants requiring regular irrigation, which will rot sagebrush roots over time and eventually kill the plant.

How long does Big Sagebrush live?

Individual plants in good growing conditions can live 50 to 100 years or more. In protected sites with favorable soils, very old plants can develop impressive trunk diameters and a gnarled, tree-like character. Most plants in disturbed or marginal sites live 20–40 years.

Does sagebrush cause allergies?

Yes. Big Sagebrush produces large quantities of wind-borne pollen from August through October, and sagebrush pollen is one of the leading causes of fall hay fever throughout the West. People with ragweed or chrysanthemum allergies may be especially sensitive to sagebrush pollen. If severe allergies are a concern, consider planting it away from windows and outdoor living areas.