Western Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta var. californica)

Corylus cornuta var. californica, commonly known as Western Hazelnut or California Hazelnut, is a magnificent deciduous shrub that represents the Pacific Coast’s own native hazelnut variety. This remarkable plant stands as one of the region’s most valuable wildlife resources, producing nutritious nuts that have sustained both indigenous peoples and wildlife for thousands of years. Distinguished from its eastern counterpart by its larger size, shorter beaks on the nut husks, and adaptation to the unique climate conditions of the Pacific Coast, the Western Hazelnut is truly a cornerstone species of Pacific Northwest ecosystems.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Corylus cornuta var. californica |

| Plant Type | Deciduous shrub or small tree |

| Mature Height | 5–12 ft |

| Height | 13-49 feet (4-15 m) |

| Sun Exposure | Partial shade to dappled sunlight |

| Water Needs | Moderate to low (drought tolerant when established) |

| Soil Type | Well-drained loam, tolerates various soil types |

| Soil pH | 6.0-7.5 (slightly acidic to neutral) |

| Bloom Time | February-April |

| Flower Color | Male: Yellow catkins; Female: Tiny red styles |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 6-9 |

Identification

Western Hazelnut is easily recognizable by its distinctive combination of features that set it apart from other Pacific Coast shrubs. This robust plant typically grows with multiple stems from the base, creating a dense, thicket-like growth pattern that provides excellent cover for wildlife. The overall form is upright and spreading, with an irregular, somewhat open crown when mature.

Leaves

The leaves are one of the most reliable identifying features of Western Hazelnut. They are alternately arranged, broadly oval to rounded, measuring 2-4 inches (5-10 cm) in length and nearly as wide. The leaf margins are distinctly double-serrated, creating a finely toothed edge that feels rough to the touch. The leaf surface is somewhat rough and hairy, particularly on the underside, giving the foliage a distinctive texture. In spring and summer, the leaves are bright to medium green, turning brilliant yellow to golden-orange in fall, creating spectacular autumn displays.

Bark

Young stems and branches have smooth, gray to brown bark that often shows horizontal lenticels (breathing pores). As the plant matures, the bark becomes slightly rougher but remains relatively smooth compared to many other shrubs. The bark on older stems may develop shallow furrows, and the overall color ranges from light gray to medium brown.

Flowers

The flowering display of Western Hazelnut is both subtle and remarkable. Male flowers appear as pendulous catkins that form in clusters during late winter or early spring, typically February through April. These catkins are 1-3 inches long, initially compact and greenish, but elongating and turning yellow as they mature and release pollen. The female flowers are tiny and inconspicuous, appearing as small red thread-like styles that emerge from seemingly ordinary buds. This monoecious flowering system (both male and female flowers on the same plant) ensures good pollination when multiple plants are present.

Fruit and Seeds

The fruit is perhaps the most distinctive feature of Western Hazelnut – the nuts are enclosed in a papery husk that extends into a prominent “beak,” giving the species its common name “beaked hazelnut.” In the Western variety, this beak is typically shorter (less than 1.2 inches or 3 cm) compared to the eastern variety. The husk is covered with fine, irritating hairs that can cause skin irritation upon contact. Inside this protective casing lies a hard-shelled nut containing a nutritious, oily kernel that is highly prized by both wildlife and humans.

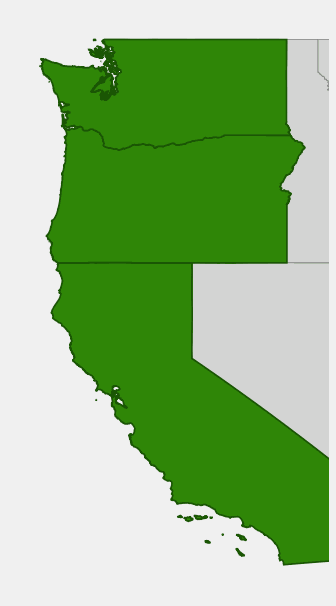

Native Range

Western Hazelnut has a remarkable range that extends along the entire Pacific Coast of North America, from British Columbia south through Washington, Oregon, and California. This extensive distribution demonstrates the plant’s adaptability to various climate conditions and ecosystems. In California, it can be found in the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada foothills, typically below 6,900 feet (2,100 m) elevation. In the Pacific Northwest, it commonly occurs from sea level up to about 2,600 feet (800 m) elevation, thriving in the region’s maritime climate.

The Western Hazelnut occupies diverse habitats within its range, from coastal forests and stream bottoms to mountain slopes and forest edges. It demonstrates remarkable ecological flexibility, growing in association with many different tree species. In the Pacific Northwest, it commonly grows beneath canopies of Douglas-fir, Western Hemlock, and Western Red Cedar, while in California it’s often found with Coast Live Oak, Pacific Madrone, and various pine species.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western Hazelnut: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Growing & Care Guide

Western Hazelnut is an exceptionally rewarding plant for Pacific Coast gardeners, offering year-round interest, valuable wildlife habitat, and delicious nuts. Its adaptability and low-maintenance requirements make it an excellent choice for naturalistic landscapes, wildlife gardens, and food forests.

Light Requirements

While Western Hazelnut can tolerate full sun in cooler coastal areas, it performs best in partial shade to dappled sunlight. In its native habitat, it typically grows as an understory plant, receiving filtered light through the forest canopy. In garden settings, morning sun with afternoon shade is ideal, especially in warmer inland areas. Too much direct sunlight in hot climates can cause leaf scorch and stress the plant, while too little light can reduce flowering and nut production.

Soil Requirements

This adaptable shrub grows well in a wide range of soil types, from sandy loams to clay soils, as long as drainage is adequate. Western Hazelnut prefers slightly acidic to neutral soils (pH 6.0-7.5) but can tolerate slightly alkaline conditions. The plant has a shallow root system, typically extending only 6 inches deep, which makes it somewhat susceptible to drought stress but also means it won’t compete heavily with deeper-rooted trees. Adding organic matter such as compost or leaf mold will improve soil structure and help retain moisture.

Water Needs

Once established (typically after the second growing season), Western Hazelnut is quite drought tolerant, reflecting its adaptation to the Pacific Coast’s dry summer climate. However, it performs best with regular water during the growing season, especially during nut development. Deep, infrequent watering is preferable to frequent shallow watering, as this encourages deeper root development. In areas with Mediterranean climates, supplemental water during the dry summer months will result in better nut production and overall plant health.

Planting Tips

Plant Western Hazelnut in fall or early spring when temperatures are cool and rainfall is adequate. Choose a location that provides some protection from hot afternoon sun and strong winds. Space plants 8-12 feet apart if growing multiple specimens, as they can spread quite widely at maturity. When planting, dig a hole twice as wide as the root ball but no deeper, as the plant prefers to be planted at the same depth it was growing in the container. Mulch around the base with 2-3 inches of organic material, keeping the mulch away from the trunk to prevent pest and disease issues.

Pruning and Maintenance

Western Hazelnut requires minimal pruning, though some maintenance can improve its appearance and productivity. Remove dead, damaged, or diseased wood in late winter or early spring before new growth begins. To encourage nut production, thin out some of the older stems every few years to allow light and air circulation to the center of the plant. Suckers can be removed if a more tree-like form is desired, or left to develop the natural thicket growth habit that provides excellent wildlife habitat.

Propagation

Western Hazelnut can be propagated by seed, cuttings, or division of suckers. Seeds require a cold stratification period of 3-4 months and may not come true to the parent plant. Semi-hardwood cuttings taken in summer can be rooted under mist, though success rates vary. The easiest method is dividing the natural suckers that develop around the base of established plants – these can be carefully removed with roots intact and transplanted in fall or early spring.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western Hazelnut stands among the most ecologically valuable plants in Pacific Coast ecosystems. Its contributions to wildlife habitat and ecosystem function are remarkable, supporting an intricate web of relationships that demonstrate the interconnectedness of native plant communities.

Pollinators and Beneficial Insects

The early spring flowering of Western Hazelnut provides crucial pollen resources when few other plants are in bloom. While the flowers are wind-pollinated rather than insect-pollinated, the abundant pollen attracts various beneficial insects including native bees, hover flies, and other early-season pollinators. The plant also hosts several specialized insects, including the hazelnut weevil (Curculio obtusus), which has co-evolved specifically with Western Hazelnut and depends entirely on it for reproduction.

Birds

Birds derive multiple benefits from Western Hazelnut throughout the year. Ruffed Grouse particularly value the protein-rich catkins and young buds, especially during winter when other food sources are scarce. The nuts are avidly consumed by Steller’s Jays, which not only eat them but also cache them for winter storage, inadvertently helping to disperse the seeds over considerable distances. Many songbirds, including finches, nuthatches, and chickadees, feed on the nuts, often working cooperatively to crack open the hard shells. The dense branching structure provides excellent nesting sites for smaller birds, while the multi-stemmed growth habit creates ideal cover for ground-foraging species.

Mammals

The ecological importance of Western Hazelnut to mammalian wildlife cannot be overstated. Squirrels, including Douglas Squirrels and various chipmunk species, are perhaps the most important consumers and dispersers of hazelnut seeds. They gather nuts extensively in fall, often burying them in soil or leaf litter where forgotten caches can germinate into new plants. Black bears consider hazelnut a premium food source, often timing their movements to coincide with nut ripening seasons. Deer and elk browse the foliage, particularly young shoots and leaves, though the Western variety is considered less palatable than its eastern counterpart. Smaller mammals such as mice and voles also consume the nuts, contributing to seed dispersal on a more localized scale.

Ecosystem Role

Western Hazelnut plays several critical ecological roles that extend well beyond its direct wildlife value. The plant’s extensive but shallow root system helps stabilize soil on slopes and provides erosion control, particularly important in areas prone to landslides. Its nitrogen-fixing ability (through mycorrhizal associations) helps enrich forest soils. The dense growth habit creates important microclimates that shelter other plants and provide refugia for various small organisms. Research has shown that Western Hazelnut can help reduce the incidence of laminated root rot in nearby conifers, making it valuable in forest health management. The plant also responds well to fire, resprouting vigorously from its root crown, which makes it an important component of fire-adapted ecosystems.

Cultural and Historical Significance

The relationship between Western Hazelnut and Pacific Coast peoples extends back thousands of years, representing one of the most enduring human-plant partnerships in North American history. Recent genetic research has revealed that Indigenous peoples, including the Gitxsan, Tsimshian, and Nisga’a, have been actively managing and cultivating Western Hazelnut for at least 7,000 years, making it one of the earliest examples of plant domestication in the region.

Traditional uses of Western Hazelnut were remarkably diverse. The nuts provided a crucial source of nutrition, particularly important as a high-fat, high-protein food that could be stored through winter months. Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated processing techniques, including roasting, grinding into meal, and pressing to extract oil. The flexible young branches were highly prized for basketry, fish traps, and baby carriers, with specific harvesting techniques designed to encourage the straight, flexible growth needed for these applications.

European explorers and settlers quickly recognized the value of Western Hazelnut. The Lewis and Clark expedition frequently bartered for hazelnuts with Indigenous peoples they encountered, and the renowned botanist David Douglas noted the plant’s abundance and importance during his Pacific Northwest explorations in the 1820s. The nuts were considered equal in quality to European hazelnuts, though the smaller size and lower yield limited commercial development compared to imported varieties.

Modern Cultivation and Breeding

Contemporary interest in Western Hazelnut extends far beyond its ornamental and ecological values. Plant breeders have recognized its exceptional disease resistance, particularly its apparent immunity to Eastern filbert blight, a devastating fungal disease that has limited hazelnut cultivation in many regions. This resistance has made Western Hazelnut invaluable in breeding programs aimed at developing new cultivars that combine disease resistance with high productivity.

Modern food forest and permaculture practitioners increasingly appreciate Western Hazelnut’s multiple functions: it produces food, provides wildlife habitat, improves soil, offers erosion control, and requires minimal inputs once established. Its ability to thrive in partial shade makes it perfect for forest gardens where it can be grown beneath taller fruit and nut trees, maximizing the productivity of limited space.

Conservation and Restoration

While Western Hazelnut is not currently considered threatened, habitat loss and fragmentation have reduced populations in some areas, particularly in urbanized coastal regions and areas converted to agriculture. Climate change poses potential challenges, as the species’ current range may shift northward or to higher elevations over time.

Restoration ecologists increasingly recognize Western Hazelnut’s value in habitat restoration projects. Its rapid establishment, wildlife benefits, and soil improvement capabilities make it an excellent choice for restoration plantings. The plant’s fire resilience also makes it valuable for post-fire rehabilitation, where it can quickly reestablish and help restore ecosystem functions while providing immediate wildlife benefits.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Western Hazelnut nuts edible?

Yes, Western Hazelnut produces fully edible nuts that are comparable in quality to commercial European hazelnuts. They can be eaten raw or roasted and are particularly prized for their rich, buttery flavor. The main difference is size – Western Hazelnut nuts are smaller than commercial varieties but are often considered superior in taste.

How long does it take for Western Hazelnut to produce nuts?

Western Hazelnut typically begins producing nuts 3-5 years after planting, though significant production usually doesn’t occur until the plant is 5-7 years old. Nut production increases with age and typically peaks when the plant reaches 10-15 years of age.

Do I need multiple plants for nut production?

While Western Hazelnut plants have both male and female flowers, cross-pollination between different plants significantly increases nut production and quality. For best results, plant at least 2-3 individuals spaced 10-15 feet apart.

Is Western Hazelnut invasive?

No, Western Hazelnut is a native plant in its range and is not considered invasive. While it can spread via root suckers, this growth habit is natural and beneficial for erosion control and wildlife habitat. In garden settings, suckers can be managed through pruning if desired.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Western Hazelnut?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington