Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)

Tsuga heterophylla, commonly known as Western Hemlock, stands as the quintessential tree of the Pacific Northwest’s coastal rainforests, creating some of the most magnificent and ecologically complex forest ecosystems on Earth. This graceful conifer, with its distinctive drooping leader and delicate foliage, forms the backbone of temperate rainforest communities from Alaska to California, defining the very essence of Pacific Coast forests. Western Hemlock demonstrates remarkable longevity and shade tolerance, often living 400-800 years and sometimes exceeding 1,200 years, making it one of the most important old-growth forest species in western North America. Its ability to thrive in the deep shade of the forest understory allows it to slowly overtake other species and eventually dominate the canopy, creating the climax forest communities that characterize the region’s most pristine ecosystems.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Tsuga heterophylla |

| Plant Type | Evergreen conifer |

| Height | 125–200 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Soil Type | Moist, well-drained, organic soils |

| Soil pH | 5.0-6.5 (acidic) |

| Bloom Time | April-June (wind-pollinated cones) |

| Flower Color | N/A (conifer) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 6-8 |

Identification

Western Hemlock is easily identified by several distinctive characteristics that set it apart from other Pacific Northwest conifers. The most recognizable feature is the drooping or nodding leader (top of the tree), which gives mature trees a distinctive graceful appearance. The needles are flat, small (about 1/2 to 3/4 inch long), and arranged in a flat spray pattern along the branches. They are dark green above with two white stomatal bands below, creating a distinctive two-toned appearance. The needles vary in length along each branch, with shorter and longer needles intermixed, giving the foliage a delicate, feathery texture that is unique among Pacific Coast conifers.

Bark and Growth Form

Young Western Hemlocks have thin, smooth, gray-brown bark that becomes increasingly furrowed and ridged with age. Mature trees develop thick, deeply furrowed bark with a reddish-brown color. The overall growth form is pyramidal when young, becoming more irregular and open with age. In forest settings, mature trees often develop a characteristic flat-topped or irregularly rounded crown.

Cones and Reproduction

Western Hemlock produces small cones that are typically 3/4 to 1 inch long, oval-shaped, and hang from branch tips. The cones mature in one season, turning from green to brown as they ripen. The small, winged seeds are dispersed by wind and can travel considerable distances, allowing the species to colonize new areas effectively.

Distinguishing from Other Conifers

Western Hemlock can be distinguished from other Pacific Northwest conifers by several key characteristics. Unlike Douglas Fir, which has grooved bark and distinctive 3-pronged bracts on cones, Western Hemlock has small oval cones without protruding bracts. The drooping leader sets it apart from Western Red Cedar, which has scale-like foliage rather than needles. Sitka Spruce has much sharper, 4-sided needles that attach individually to branches, while Western Hemlock’s flat needles attach in a more organized spray pattern.

Seasonal Changes

Throughout the year, Western Hemlock displays subtle but beautiful changes. In spring, new growth appears as bright green tips contrasting beautifully with the darker mature foliage. The small cones begin developing in late spring, starting as tiny green structures that gradually mature to brown by fall. During winter, the evergreen foliage provides consistent structure and color in the forest, often collecting snow and creating the iconic winter scenes of Pacific Northwest forests.

Native Range

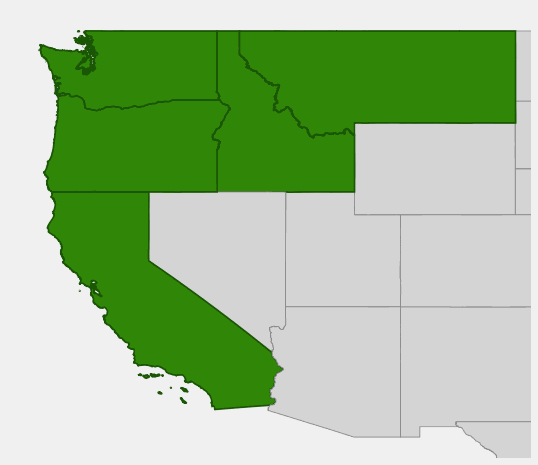

Native range of Western Hemlock. USDA (County-Level Data)

Western Hemlock has a distinctive coastal distribution, extending from southeast Alaska south to northern California, generally within 100 miles of the Pacific Ocean. The species is closely associated with the maritime climate of the Pacific Coast, thriving in areas that receive abundant precipitation and experience moderate temperatures year-round.

Growing & Care Guide

Western Hemlock is challenging to grow outside of its native range due to its specific requirements for cool, moist conditions and acidic soils. However, within its natural habitat range, it can be an excellent choice for large-scale plantings, restoration projects, and properties with adequate space and appropriate growing conditions.

Environmental Requirements

Western Hemlock requires consistent moisture and cool temperatures to thrive. It performs best in areas that receive significant annual precipitation (typically 30+ inches) and experience moderate temperatures year-round. The species is highly shade tolerant and can grow successfully under the canopy of other trees, making it valuable for understory plantings in appropriate climates.

Soil Preferences

The tree prefers well-drained, acidic soils rich in organic matter. It thrives in the naturally acidic conditions created by coniferous forest litter and requires soils that retain moisture but do not become waterlogged. Adding organic matter such as compost or well-rotted pine needles can help create suitable soil conditions.

Planting and Establishment

Plant Western Hemlock in fall or early spring when temperatures are cool and moisture is abundant. The tree establishes slowly but steadily, requiring patience from gardeners. Protect young trees from direct sunlight and strong winds, as they prefer the protected environment of the forest understory during their early years.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Western Hemlock forests support some of the richest and most complex ecosystems in North America. The tree’s longevity, massive size potential, and ability to create multilayered forest canopies make it a keystone species that supports an incredible diversity of wildlife and plant species.

Old-Growth Forest Ecosystems

Mature Western Hemlock forests create the complex structural diversity that defines old-growth ecosystems. These ancient forests support numerous endangered and sensitive species, including the Northern Spotted Owl, Marbled Murrelet, and various salamander species that depend on the unique microhabitats created by these towering trees.

Wildlife Habitat

The dense canopy and complex branching structure provide nesting sites for numerous bird species, while the thick bark of older trees offers habitat for various insects and small organisms. The seeds are consumed by various bird species, including finches, siskins, and chickadees, while the needles provide browse for deer and elk.

Ecosystem Services

Western Hemlock provides numerous ecosystem services including carbon sequestration, soil stabilization, and water cycle regulation. The deep root systems help prevent erosion, while the massive canopies moderate local climate conditions and provide crucial habitat for countless species of plants, animals, and fungi.

Forest Structure and Habitat Creation

Western Hemlock’s most significant ecological contribution lies in its ability to create the complex three-dimensional habitat structure that defines old-growth Pacific Northwest forests. The species’ extreme longevity and massive size potential allow individual trees to create unique microhabitats at different elevations within the forest canopy. Mature Western Hemlocks develop irregular crowns with dead tops (snags) that provide nesting cavities for woodpeckers, while fallen branches create nurse logs that support entire communities of plants, fungi, and invertebrates.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Western Hemlock holds profound significance in the cultures of Pacific Northwest Indigenous peoples, who have utilized every part of this magnificent tree for countless generations. The Squaxin Island Tribe, Skokomish, Quinault, and many other Coast Salish nations developed sophisticated relationships with Western Hemlock that encompassed practical, spiritual, and ecological dimensions of life in the coastal temperate rainforest.

The inner bark of Western Hemlock provided a crucial food source during times of scarcity. Indigenous peoples would carefully harvest the cambium layer in spring when the sap was running, drying it in cakes for winter storage. This nutritious inner bark could be ground into flour, mixed with other foods, or eaten directly. The bark was harvested sustainably, with only portions taken from large trees to ensure their survival. The outer bark was used medicinally to treat various ailments including coughs, colds, and skin conditions.

The small branches and twigs were woven into baskets, mats, and other utilitarian items. The flexible young branches were particularly prized for making fish traps and other tools requiring bend-resistant materials. The pitch from Western Hemlock was used to waterproof canoes and other wooden items, while the wood itself provided material for tools, implements, and construction when other preferred woods like Western Red Cedar were unavailable.

During European colonization and the development of the Pacific Northwest timber industry, Western Hemlock initially was considered less valuable than Douglas Fir and other species. However, by the early 1900s, technological advances made it possible to utilize Western Hemlock effectively for lumber, pulp, and paper production. The species became crucial to the region’s forest products industry, particularly for pulp and paper manufacturing due to its long, strong fibers.

Today, Western Hemlock remains an important timber species, though old-growth forests containing the largest specimens are now protected in many areas due to their irreplaceable ecological value. The species is increasingly recognized not just for its economic potential but for its critical role in supporting the complex ecosystems that define the Pacific Northwest’s natural heritage. Modern restoration efforts often focus on reestablishing Western Hemlock in areas where it was historically abundant, recognizing its keystone role in creating the multilayered forest structure that supports the region’s exceptional biodiversity.

The thick, furrowed bark of older Western Hemlocks provides habitat for numerous invertebrate species, including beetles, spiders, and other arthropods that form the foundation of forest food webs. These invertebrates, in turn, support populations of insectivorous birds, amphibians, and small mammals. The complex branching structure of mature trees creates numerous microhabitats with varying light, moisture, and temperature conditions, supporting diverse communities of epiphytic plants including mosses, lichens, and ferns.

Mycorrhizal Networks

Western Hemlock participates in extensive mycorrhizal networks that connect individual trees and facilitate nutrient sharing throughout forest communities. These fungal partnerships are essential for the tree’s ability to thrive in the nutrient-poor soils typical of Pacific Northwest forests. The mycorrhizal networks also support other plant species and contribute to the overall resilience and stability of forest ecosystems. When Western Hemlocks die and decompose, they release accumulated nutrients back into these networks, supporting forest regeneration for decades or even centuries.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Western Hemlock: Western Oregon & Western Washington

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Western Hemlock grow outside the Pacific Northwest?

Western Hemlock requires very specific climatic conditions – cool, moist maritime climate with abundant precipitation. It generally cannot survive in hot, dry, or continental climates. Successful cultivation is typically limited to areas with similar conditions to its native range, such as coastal regions with mild temperatures and high humidity year-round.

How long does it take for Western Hemlock to reach maturity?

Western Hemlock is a slow-growing tree that can take 80-120 years to reach reproductive maturity and several centuries to develop old-growth characteristics. The largest specimens, some over 1,000 years old, represent centuries of growth and are irreplaceable components of Pacific Northwest ecosystems.

Is Western Hemlock the same as Eastern Hemlock?

No, Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) and Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) are different species with different characteristics and ranges. Western Hemlock is generally larger, has different needle arrangements, and is adapted to the maritime climate of the Pacific Coast, while Eastern Hemlock is found in eastern North America and has different ecological requirements.

Why are Western Hemlock forests so important for conservation?

Old-growth Western Hemlock forests represent some of the most complex and biodiverse ecosystems in North America. These ancient forests support numerous endangered and sensitive species that cannot survive in younger forests, including the Northern Spotted Owl and Marbled Murrelet. They also provide crucial ecosystem services including carbon storage, water regulation, and climate moderation.

Can I plant Western Hemlock in my garden?

Western Hemlock can be planted in gardens within its native range if you have appropriate conditions – cool, moist climate, acidic soil, and adequate space for a very large tree. However, it’s important to consider that these trees can eventually reach over 200 feet tall and live for centuries, making them suitable only for very large properties or specialized restoration projects.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Western Hemlock?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: Oregon · Washington