Virgin’s Bower (Clematis virginiana): Native Plant Guide

Last updated: February 18, 2026

Clematis virginiana, commonly known as Virgin’s Bower, Wild Clematis, or Devil’s Darning Needles, is a vigorous native climbing vine that adorns eastern North American woodlands and woodland edges with cascades of fragrant white flowers in late summer. This member of the Ranunculaceae (buttercup) family is one of the most widespread and recognizable native vines in its range, capable of climbing 10 to 20 feet high as it scrambles over shrubs, fences, and trees with the help of its twisting leaf petioles that serve as natural tendrils.

What makes Virgin’s Bower particularly captivating is its remarkable seasonal transformation. In August and September, the vine produces masses of small, creamy-white flowers that fill the air with a subtle, sweet fragrance and attract numerous pollinators. These blooms give way to equally spectacular seed heads — fluffy, silver-white plumes that persist well into winter, earning the plant its evocative common name “Devil’s Darning Needles.” The contrast between the delicate summer flowers and the dramatic winter seed displays makes this vine a year-round garden asset.

Virgin’s Bower thrives in a variety of conditions from full sun to partial shade and tolerates both moist and moderately dry soils, making it an excellent choice for naturalizing difficult areas, providing wildlife habitat, or creating screening along property boundaries. Its rapid growth, attractive flowers, and exceptional wildlife value — supporting numerous pollinators and providing nesting sites for birds — make it an outstanding addition to native plant gardens, woodland restoration projects, and any landscape seeking authentic eastern woodland character.

Identification

Virgin’s Bower is a deciduous, woody climbing vine that can reach 10 to 20 feet in length, occasionally growing even taller when growing over large trees or structures. The vine climbs by means of its twisted leaf petioles (leaf stems) that wrap around supports like tendrils, rather than by true tendrils or adhesive pads. The overall growth habit is vigorous and somewhat aggressive, with multiple stems arising from the base to create dense, tangled masses that can completely cover supporting vegetation.

Stems & Bark

The stems are slender, woody, and somewhat ribbed or grooved, typically growing 1/4 to 1/2 inch in diameter. Young stems are green to reddish-brown, becoming more woody and darker with age. The bark on older stems is light brown to grayish and may develop shallow furrows. The stems have a pithy center and tend to be somewhat brittle, breaking cleanly when bent sharply. During winter, the leafless stems create an intricate network of woody vines that can be quite ornamental against snow or dark backgrounds.

Leaves

The leaves are opposite, compound, and typically divided into three leaflets (trifoliate), though occasionally they may have five leaflets. Each leaflet is oval to ovate, 2 to 4 inches long, with a pointed tip and serrated margins. The leaflets have a somewhat leathery texture and are bright green above and paler beneath. The most distinctive feature is the long, twisted petioles (leaf stems) that serve as climbing organs — these petioles coil around twigs, wire, or other supports, anchoring the vine as it climbs. In autumn, the foliage turns yellow before dropping, revealing the intricate structure of the woody stems.

Flowers

The flowers are Virgin’s Bower’s most celebrated feature — small, creamy-white, and borne in dense, showy clusters (panicles) that can be 4 to 6 inches across. Individual flowers are about 3/4 inch in diameter and lack true petals; instead, they have four petal-like sepals that are white to cream-colored. The most striking feature of each flower is the numerous prominent stamens that create a fuzzy, bottlebrush-like appearance in the center. The flowers are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers occur on separate plants — male flowers tend to be showier with more prominent stamens, while female flowers are smaller and less conspicuous.

Blooming occurs from July through September, with peak flowering in August. The flowers are mildly fragrant, particularly in the evening, and are arranged in large, branched clusters that can nearly obscure the foliage when the vine is in full bloom. The overall effect is spectacular, with entire hillsides or woodland edges appearing to be draped in white lace.

Fruit & Seeds

The fruit is perhaps the most distinctive and long-lasting feature of Virgin’s Bower. Following pollination, female flowers develop into clusters of small, dry, one-seeded fruits (achenes) topped with long, feathery, silvery-white styles that can be 1 to 2 inches long. These create the spectacular “Devil’s Darning Needles” seed heads that give the plant much of its ornamental value. The seed heads begin developing in late summer and persist well into winter, becoming even more prominent after the leaves fall. They catch and hold snow beautifully, creating some of the most striking winter displays in the native plant world.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Clematis virginiana |

| Family | Ranunculaceae (Buttercup) |

| Plant Type | Deciduous Climbing Vine |

| Mature Height | 10–20 ft (3–6 m) climbing |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun to Part Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | July–September |

| Flower Color | White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

Native Range

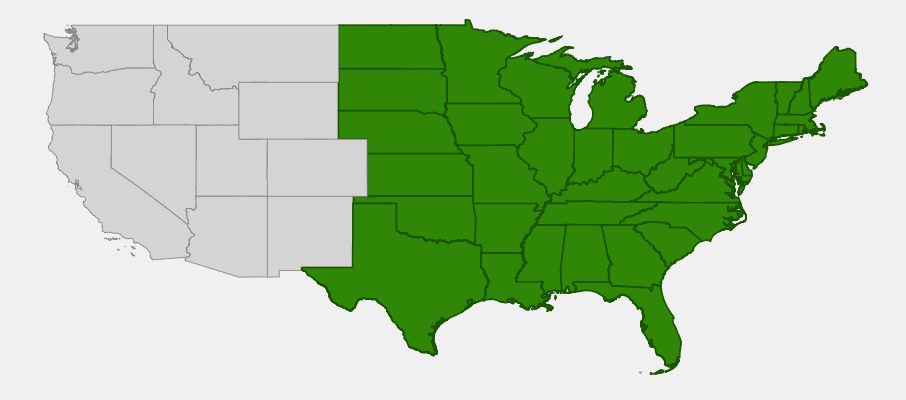

Virgin’s Bower has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American clematis, stretching from southern Canada south to northern Florida and from the Atlantic coast west to the Great Plains. This broad distribution reflects the species’ adaptability to various climate conditions and habitat types. The vine is most common in the eastern deciduous forests but extends into prairie edges and riparian areas in the western portions of its range.

Within its native range, Virgin’s Bower is typically found in woodland edges, forest openings, along streams and rivers, in hedgerows, and in other semi-shaded to open habitats where it can find suitable support for climbing. It shows a particular affinity for disturbed areas and forest edges, often being among the first woody plants to colonize abandoned fields that are reverting to forest. The species grows from sea level to moderate elevations in the mountains, tolerating a wide range of soil and moisture conditions.

Historically, Virgin’s Bower was an important component of eastern woodland edge communities and was commonly found growing over shrubs in prairie-forest transition zones. While still widespread and locally common throughout much of its range, populations in some areas have been reduced by habitat fragmentation and the introduction of aggressive exotic vines. However, the species remains one of the most reliable and widely available native vines for restoration and landscaping projects.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Virgin’s Bower: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Virgin’s Bower is one of the easiest and most rewarding native vines to grow, adapting to a wide range of conditions and providing spectacular displays with minimal care. Its vigorous nature and tolerance for various growing conditions make it an excellent choice for naturalizing areas, creating quick screens, or adding vertical interest to native plant gardens. However, its enthusiastic growth habit means it needs appropriate placement and occasional management to prevent it from overwhelming nearby plants.

Light Requirements

Virgin’s Bower is remarkably adaptable to different light conditions, thriving in everything from full sun to partial shade. In full sun locations, the vine produces the most abundant flowering and tends to have denser growth, while in partial shade it may be somewhat more open but still flowers well. The vine actually benefits from having its roots in cooler, shadier conditions while allowing the top growth to reach toward sunlight — a common preference among woodland edge plants. Avoid deep shade locations, as this will result in sparse flowering and weak, straggly growth.

Soil & Water Requirements

This adaptable vine tolerates a wide range of soil conditions, from clay to sandy soils, and from slightly acidic to neutral pH (6.0-7.5). It prefers well-drained soil but tolerates both moist and moderately dry conditions once established. In nature, it’s often found in rich, organic woodland soils, so incorporating compost or leaf mold into the planting area will encourage robust growth. The vine is somewhat drought-tolerant once established but performs best with consistent moisture, especially during dry summer periods when it’s flowering and setting seed.

Support & Placement

Virgin’s Bower climbs by twisting its leaf petioles around supports, so it needs something to grab onto — this can be trellises, fences, shrubs, trees, or even other vines. The supports should be relatively thin (under 2 inches in diameter) for the petioles to successfully wrap around. When growing over shrubs or small trees, the vine rarely causes damage due to its relatively light weight, but it should be kept away from valuable ornamental plants that might be overwhelmed. Allow 6-10 feet of space between plants, as mature vines can spread considerably.

Planting & Establishment

Plant Virgin’s Bower in spring after the last frost or in fall at least 6-8 weeks before hard freeze. Dig a hole twice as wide as the root ball and plant at the same depth as it was growing in the container. Water thoroughly after planting and maintain consistent moisture during the first growing season. The vine establishes quickly and may begin climbing and flowering in its first year if planted early in the season. Mulching around the base helps retain moisture and suppress competing weeds.

Pruning & Maintenance

Virgin’s Bower benefits from annual pruning but is forgiving of different pruning approaches. The best time to prune is in late winter or very early spring before new growth begins. The vine can be cut back quite severely if needed — even to within 12 inches of the ground — and will regrow vigorously. For general maintenance, remove any dead, damaged, or weak growth, and thin out the densest areas to improve air circulation. If growing over valuable plants, periodic pruning may be needed to prevent the vine from overwhelming its support.

Some gardeners prefer to leave the seed heads for winter interest and bird food, then prune in early spring. Others cut back the vines in fall after enjoying the seed display. Both approaches work well — the choice depends on your garden design preferences and the needs of local wildlife.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Virgin’s Bower provides exceptional value for native wildlife throughout multiple seasons, serving as an important nectar source during late summer when many other plants have finished flowering, and providing critical nesting sites and winter cover. Its ecological importance extends far beyond its ornamental value, making it a keystone species for woodland edge habitat restoration.

For Pollinators

The late-season flowers of Virgin’s Bower are crucial for many pollinators preparing for winter. The abundant, nectar-rich blooms attract a diverse array of native bees, including bumble bees, sweat bees, mining bees, and leafcutter bees. Butterflies are regular visitors, particularly skippers and smaller species, along with beneficial wasps and hoverflies. The flowers are also important for beetles, particularly those that overwinter as adults and need late-season nutrition. The timing of Virgin’s Bower’s bloom — when many other native plants have finished flowering — makes it particularly valuable in the pollinator landscape.

For Birds

Birds benefit from Virgin’s Bower in multiple ways throughout the year. During nesting season, the dense, tangled growth provides excellent nesting sites for many small bird species, including American Goldfinches, Indigo Buntings, and various wrens and vireos. The vine’s structure creates hidden nesting pockets that offer protection from predators and weather. In fall and winter, birds use the persistent seed heads for nesting material and the seeds themselves provide food, particularly for goldfinches and other small seed-eating species. The dense winter structure also provides important shelter and thermal cover during harsh weather.

For Other Wildlife

Small mammals, particularly chipmunks and squirrels, occasionally consume the seeds and use the fibrous bark and stems for nesting material. The vine’s dense growth creates corridors and cover for small mammals moving through the landscape. Various insects use the stems and leaf litter beneath the vine for overwintering habitat, while the flowers support numerous beneficial insects that help control garden pests. The foliage occasionally serves as food for various moth caterpillars, though it’s not a primary host plant for any major butterfly or moth species.

Ecosystem Services

Virgin’s Bower plays important ecological roles beyond direct wildlife support. Its rapid growth and dense coverage make it excellent for erosion control on slopes and streambanks. The vine helps stabilize soil with its extensive root system while providing quick coverage for disturbed areas. In restoration projects, it often serves as a “nurse plant,” providing shelter and favorable microclimatic conditions for tree seedlings and other slower-growing native plants. The annual leaf drop contributes organic matter to the soil, improving soil structure and supporting beneficial soil organisms.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Virgin’s Bower has a rich history of use by Indigenous peoples of eastern North America, who valued the plant for both medicinal and practical purposes. Various tribes developed uses for different parts of the plant, though it was always used with considerable caution due to the plant’s potentially toxic properties.

Indigenous Uses

Several eastern tribes, including the Cherokee, Iroquois, and Ojibwe, used Virgin’s Bower medicinally, though always with great care due to the plant’s irritating properties. The Cherokee used extremely dilute root preparations for kidney problems and as a wash for skin conditions, while the Iroquois used it in compound remedies for colds and fever. The Menominee tribe used the plant externally for treating cuts and wounds, taking advantage of its antimicrobial properties while avoiding internal use.

Some tribes used the strong, fibrous stems for basketry and cordage, though this required careful preparation to avoid skin irritation from the plant’s natural compounds. The fluffy seed heads were occasionally used as tinder for fire-starting, as they catch flame easily when dry.

Colonial and Early American Period

European colonists learned about Virgin’s Bower from Indigenous peoples and incorporated it into their folk medicine practices, though often with mixed results due to the plant’s variable potency and potential toxicity. The plant was mentioned in several early American herbals as a treatment for skin conditions and joint pain, applied externally as poultices or washes. However, medical use declined as safer alternatives became available.

The vine gained popularity as an ornamental plant in the 19th century, particularly for covering unsightly structures and creating quick screens. Garden writers of the period praised its rapid growth, attractive flowers, and spectacular seed displays, recommending it for “wild gardens” and naturalistic landscapes.

Modern Applications

Today, Virgin’s Bower is valued primarily for its ecological and ornamental benefits rather than medicinal uses. It has become a popular choice for native plant landscaping, restoration projects, and wildlife gardens. The vine is frequently used in erosion control projects, particularly along streams and on slopes where its rapid establishment and spreading root system provide quick stabilization. Modern gardeners appreciate its low maintenance requirements, wildlife value, and year-round interest.

The plant has also gained recognition in sustainable landscaping practices, where its ability to quickly create habitat and provide ecosystem services makes it valuable for green infrastructure projects and urban wildlife corridors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Virgin’s Bower invasive or aggressive?

Virgin’s Bower is vigorous and can spread rapidly, but it’s a well-behaved native plant that doesn’t typically escape cultivation to become problematic in natural areas. However, it can overwhelm smaller plants in garden settings if not properly managed. Regular pruning and thoughtful placement will keep it under control while allowing you to enjoy its many benefits.

Will Virgin’s Bower damage structures or other plants?

Unlike some vines that can damage structures with strong roots or adhesive pads, Virgin’s Bower climbs only by twisting leaf petioles and is relatively lightweight. It rarely damages healthy trees or sturdy structures. However, it should be kept away from valuable ornamental plants that might be overwhelmed, and it may need occasional pruning when growing over shrubs.

Can I grow Virgin’s Bower from seed?

Yes, Virgin’s Bower can be grown from seed, but it requires cold stratification (3-4 months of cold, moist conditions) for good germination. Seeds are best collected when the feathery plumes are fully developed but before they disperse naturally. Stratified seeds can be started indoors in late winter or direct-seeded in fall for natural cold treatment. However, purchasing plants from nurseries is often easier and more reliable.

How long does it take Virgin’s Bower to establish and flower?

Virgin’s Bower is fast-growing and typically begins climbing and may even flower lightly in its first year if planted early in the season. Full, spectacular flowering displays usually develop by the second or third year. The vine reaches maturity quickly, often achieving most of its potential size within 3-4 years under good growing conditions.

Is Virgin’s Bower deer resistant?

Virgin’s Bower has moderate deer resistance due to its somewhat bitter taste and irritating sap compounds. While deer may occasionally browse it, particularly young growth, it’s generally not a preferred food source. However, in areas with severe deer pressure, protection may be needed during establishment.

Should I leave the seed heads for winter, or cut them back?

This is largely a matter of personal preference and garden style. The feathery seed heads provide spectacular winter interest and important wildlife value, so many gardeners leave them until late winter or early spring. Others prefer a neater appearance and cut back the vine in late fall after enjoying the initial seed display. Both approaches are acceptable, and the vine will respond well to either management strategy.

Looking for a nursery that carries Virgin’s Bower?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota