Prairie Coneflower (Ratibida columnifera)

Ratibida columnifera, commonly known as Prairie Coneflower, Mexican Hat, or Upright Prairie Coneflower, is one of the most distinctive and resilient wildflowers of North America’s Great Plains. This remarkable member of the Asteraceae (sunflower) family earned its colorful common name “Mexican Hat” from the flower’s unique appearance — drooping yellow or red-orange ray petals surrounding a prominent, thimble-shaped dark brown center that resembles the upturned brim of a sombrero.

Native across a vast swath of prairie from Canada to Mexico, Prairie Coneflower is a testament to the adaptability and beauty of grassland ecosystems. Growing 1.5 to 3 feet tall with deeply divided, gray-green leaves, this perennial herb produces its unmistakable flowers from late spring through fall, creating waves of color across native prairies, roadsides, and disturbed soils. The plant’s remarkable drought tolerance and ability to thrive in poor soils made it a cornerstone species of the original tallgrass and mixed-grass prairie ecosystems.

What makes Prairie Coneflower truly special is its ecological generosity — its flowers provide nectar for dozens of butterfly and bee species, its seeds feed countless birds, and its deep taproot helps build soil structure while accessing water unavailable to shallow-rooted plants. In the garden, it brings authentic prairie character with minimal care, self-seeding to create naturalized colonies while never becoming invasive. For anyone seeking to capture the spirit of America’s grasslands, Prairie Coneflower offers both visual drama and deep ecological connections.

Identification

Prairie Coneflower is unmistakable once you know its key features. This upright perennial herb typically grows 1.5 to 3 feet tall (occasionally reaching 4 feet in ideal conditions), forming clumps from a deep taproot. The entire plant has a distinctive gray-green color and rough, hairy texture that helps it conserve moisture in prairie conditions.

Stems & Growth Form

The stems are erect, branching, and covered with short, stiff hairs (hispid) that give them a rough, sandpaper-like texture. Multiple stems arise from the base, creating a bushy appearance. The plant’s overall architecture is designed for wind resistance — sturdy enough to withstand prairie storms yet flexible enough to bend without breaking.

Leaves

The leaves are deeply pinnately divided into narrow, linear segments, giving them an almost feathery appearance. This fine division reduces surface area for water loss while still allowing adequate photosynthesis — a perfect adaptation to the drought-prone prairie environment. The leaves are arranged alternately on the stems and become smaller toward the top of the plant. Like the stems, they’re covered with short, rough hairs that help reduce water loss.

Flowers

The flowers are the plant’s crowning glory and most distinctive feature. Each flower head consists of a prominent, dark brown to almost black, columnar receptacle (the “cone”) surrounded by 3–7 drooping ray petals. This central cone is what gives the plant its species name “columnifera” — meaning “column-bearing.” The cone starts small and elongates as the flower matures, eventually becoming thimble-shaped and up to ¾ inch tall.

The ray petals are typically bright yellow, but color forms with red or orange petals tipped with yellow are also common. These drooping petals create the “Mexican Hat” appearance that makes the flowers so distinctive. The blooming season is remarkably long — from May through October — with individual plants producing dozens of flower heads over the growing season.

Seeds & Fruit

As the flowers mature, the dark receptacle fills with tiny, wedge-shaped achenes (small, dry fruits). Each receptacle can produce hundreds of seeds, which are dispersed by wind and wildlife. The seeds have small bristles or scales that help with dispersal, and they remain viable in the soil for several years, allowing the plant to establish in disturbed areas.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Ratibida columnifera |

| Family | Asteraceae (Sunflower) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 1.5–3 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Full Sun |

| Water Needs | Low to Moderate |

| Bloom Time | May – October |

| Flower Color | Yellow, Red-orange (black cone centers) |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 3–9 |

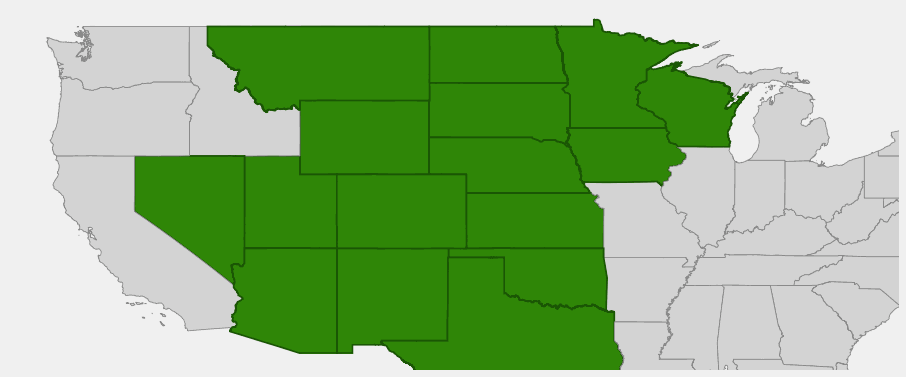

Native Range

Prairie Coneflower has one of the most extensive native ranges of any North American wildflower, stretching from southern Canada south to Mexico and from the Rocky Mountain foothills east to the Great Lakes region. This vast distribution reflects the plant’s remarkable adaptability to different climate zones and soil types, though it reaches its greatest abundance in the Great Plains where it evolved as a dominant prairie species.

The species thrives across the historic tallgrass, mixed-grass, and shortgrass prairie ecosystems that once covered much of central North America. It’s particularly common in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, and eastern Colorado, where it grows alongside native grasses like Big Bluestem, Little Bluestem, Buffalo Grass, and Blue Grama. The plant’s deep taproot — often extending 6-15 feet into the soil — allows it to access groundwater and survive the periodic droughts that characterize continental grassland climates.

Today, Prairie Coneflower is often found along roadsides, in old fields, and on disturbed sites, where its pioneer nature helps it establish quickly. While much of its original prairie habitat has been converted to agriculture, the species has shown remarkable resilience, maintaining healthy populations across its range and readily colonizing suitable habitat when seeds are available.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Prairie Coneflower: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota · Nebraska & Kansas · Montana & Wyoming

Growing & Care Guide

Prairie Coneflower is one of the easiest native wildflowers to grow, requiring minimal care once established. Its natural drought tolerance and adaptability to various soil conditions make it an excellent choice for low-maintenance native gardens, prairie restorations, and xeriscaping projects.

Light

Prairie Coneflower requires full sun to perform its best. It evolved in open grasslands with minimal shade, so provide at least 6-8 hours of direct sunlight daily. In partial shade, the plants will grow taller and more spindly as they reach for light, and flowering will be reduced. Full sun produces the most compact, floriferous plants with the best drought tolerance.

Soil & Water

One of Prairie Coneflower’s greatest strengths is its tolerance of poor soils. It thrives in sandy, rocky, clay, or alkaline soils that challenge many other plants. The key requirement is good drainage — standing water will kill the plants. Once established, Prairie Coneflower is extremely drought tolerant thanks to its deep taproot, which can extend 10-15 feet into the soil. Water regularly the first year to help establish the root system, then reduce watering significantly. Mature plants rarely need supplemental irrigation except in severe drought.

Planting Tips

Prairie Coneflower can be grown from seed or transplants. Seeds require a cold stratification period (60-90 days of moist cold), so direct sow in fall or cold-treat seeds in the refrigerator for spring planting. Transplants establish easily when planted in spring or early fall. Space plants 18-24 inches apart to allow for their mature spread. The deep taproot makes Prairie Coneflower difficult to transplant once established, so choose the location carefully.

Pruning & Maintenance

Prairie Coneflower requires virtually no maintenance. Deadhead spent flowers to prolong blooming, or leave the seed heads for wildlife and winter interest. The distinctive dark cones provide excellent structure in winter gardens and feed birds. Cut back the foliage in late fall or early spring. The plants may self-seed freely, which is desirable for naturalized areas but may require management in formal gardens.

Landscape Uses

Prairie Coneflower excels in many garden situations:

- Prairie & meadow gardens — essential for authentic grassland restorations

- Xeriscaping — thrives with minimal water once established

- Pollinator gardens — provides nectar throughout the growing season

- Naturalized areas — self-seeds to create informal colonies

- Cut flower gardens — distinctive flowers are excellent for arrangements

- Roadside plantings — tolerates road salt and harsh conditions

- Rain gardens — handles both drought and occasional flooding

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Prairie Coneflower is a keystone species for grassland wildlife, providing food and habitat for dozens of species throughout its long growing season. Its ecological importance extends far beyond its ornamental value, making it essential for anyone creating wildlife-friendly landscapes.

For Birds

The abundant seeds of Prairie Coneflower are consumed by numerous bird species, including American Goldfinches, Lesser Goldfinches, Pine Siskins, various sparrows, and quail. The seeds ripen continuously from mid-summer through fall, providing a reliable food source during critical migration periods. The sturdy stems and persistent seed heads also provide perching sites and winter shelter for small birds.

For Mammals

White-tailed deer and pronghorn occasionally browse the foliage, though the rough, hairy texture makes it less palatable than many plants. Small mammals like voles and prairie dogs may eat the roots and seeds. The dense growth provides cover for small mammals and nesting materials for various species.

For Pollinators

Prairie Coneflower is exceptional for pollinators, attracting over 30 species of native bees, including sweat bees, leafcutter bees, and small carpenter bees. Butterflies frequently visit the flowers, with Painted Ladies, Skippers, and various blues being regular visitors. The long bloom season — May through October — provides consistent nectar when many other prairie flowers have finished blooming. Beneficial insects like hover flies and predatory beetles also utilize the flowers for nectar and pollen.

Ecosystem Role

Prairie Coneflower’s deep taproot plays a crucial role in prairie ecosystem health. The roots break up hardpan soils, improve drainage, and create channels for water infiltration. As the roots decompose, they add organic matter deep in the soil profile. The plant’s ability to colonize disturbed areas makes it valuable for prairie restoration and erosion control. Its allelopathic properties may help suppress some weedy species, contributing to the stability of native plant communities.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Prairie Coneflower has a rich history of use by Indigenous peoples across the Great Plains, who valued both its medicinal properties and its role as an indicator of healthy grassland ecosystems. Many Plains tribes, including the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Kiowa, incorporated various parts of the plant into their traditional medicine systems.

The leaves and flowers were commonly used to make poultices for treating wounds, burns, and snakebites. A tea made from the plant was used to treat stomach ailments and as a general tonic. Some tribes used the plant in ceremonial contexts, recognizing its connection to the spiritual health of the prairie ecosystem. The distinctive flowers also served as natural dyes, producing yellow and orange colors for decorating clothing and ceremonial items.

European settlers quickly adopted Prairie Coneflower for similar medicinal uses, and it became a common component of frontier medicine chests. The plant was harvested commercially for the patent medicine trade in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Folk names like “Rattlesnake Medicine” reflect its reputation for treating venomous bites, though modern science has not validated these traditional uses.

Today, Prairie Coneflower is valued primarily for its ecological and ornamental qualities. It has become a symbol of prairie conservation efforts and is widely planted in restoration projects across the Great Plains. The distinctive flower shape has inspired artists and photographers, making it one of the most recognizable symbols of American grasslands. Native plant enthusiasts treasure it for its authentic prairie character and minimal care requirements, while conservationists appreciate its role in supporting declining grassland wildlife populations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are some Prairie Coneflower flowers yellow and others red?

Prairie Coneflower exhibits natural color variation within the species. The typical form has bright yellow ray petals, but red or orange forms (sometimes called “Red Mexican Hat”) are also common. This genetic variation is natural and both forms may appear in the same population. Some plants even produce flowers with yellow petals tipped in red.

How deep do Prairie Coneflower roots grow?

Prairie Coneflower develops an extensive taproot system that typically reaches 6-15 feet deep, with some reports of roots extending even deeper in drought conditions. This remarkable root system is what gives the plant its exceptional drought tolerance and makes it difficult to transplant once established.

Will Prairie Coneflower spread and take over my garden?

Prairie Coneflower spreads primarily by seed, not by runners or rhizomes. While it may self-seed in favorable conditions, it’s not aggressive and is easily managed. The seedlings are also easy to identify and remove if needed. Most gardeners find the self-seeding behavior desirable for creating naturalized drifts.

Can I grow Prairie Coneflower in containers?

While possible, Prairie Coneflower is not ideally suited for container growing due to its deep taproot system. If you must grow it in containers, choose very deep pots (at least 18 inches) and be prepared to provide more frequent watering, as the plant won’t be able to access deep groundwater as it would in the ground.

When should I plant Prairie Coneflower seeds?

Seeds can be planted in fall (October-November) for natural cold stratification over winter, or in spring after cold-treating the seeds in the refrigerator for 60-90 days. Fall seeding is often more successful as it mimics the plant’s natural germination cycle. Seeds need light to germinate, so barely cover them with soil.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Prairie Coneflower?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota