Red Baneberry (Actaea rubra)

Actaea rubra, commonly known as Red Baneberry, Snakeberry, or Cohosh, is a distinctive perennial herb that brings quiet elegance to the shadowy understory of North American forests. This member of the Ranunculaceae (buttercup) family is renowned for its delicate white flower clusters that bloom in late spring, followed by glossy red berries that provide striking color against the deep greens of the woodland floor throughout summer and fall.

Native to the cool, moist forests of northern and montane regions from Alaska to Newfoundland and south through the northern United States, Red Baneberry is a true shade specialist. Growing 1 to 2 feet tall with distinctively compound leaves, this woodland wildflower exemplifies the subtle beauty of forest flora. Its feathery white flower clusters (racemes) appear in April through June, creating ethereal patches of light in the dappled shadows beneath deciduous and mixed forest canopies.

What makes Red Baneberry particularly fascinating is its dual nature — while undeniably beautiful, all parts of the plant contain potent toxins that have earned it the ominous “baneberry” name. Yet this very toxicity plays an important ecological role, as the conspicuous red berries serve as a warning system to potential browsers while still providing food for certain bird species that can safely consume them. For gardeners seeking to recreate authentic woodland ecosystems, Red Baneberry offers both botanical interest and a connection to the deep forest environments where it naturally thrives.

Identification

Red Baneberry is easily recognized by its distinctive growth form and seasonal progression through flowers, foliage, and fruit. This herbaceous perennial typically reaches 1 to 2 feet in height, forming loose clumps from thick, creeping rhizomes. The plant’s overall appearance changes dramatically through the seasons, making it interesting to observe year-round.

Stems & Growth Form

The stems are erect, smooth, and relatively stout, arising from thick underground rhizomes. They’re typically unbranched below the inflorescence and have a distinctive reddish tinge, particularly where they support the flower clusters. The stems are sturdy enough to support the weight of the berry clusters even when fully laden with fruit in late summer.

Leaves

The leaves are the plant’s most distinctive vegetative feature — large, compound, and elegantly divided. Each leaf is bipinnately or tripinnately compound (divided twice or three times), creating a delicate, fern-like appearance. The individual leaflets are sharply toothed, ovate to oblong in shape, and have a fresh green color that provides beautiful contrast in shaded gardens. Typically, each plant has 2-3 large compound leaves that can span 8-12 inches in both length and width.

Flowers

The flowers appear in late spring (April-June) in dense, fluffy terminal racemes that rise above the foliage. Each raceme contains 15-50 small, white flowers that lack petals — what appears to be petals are actually numerous stamens with white filaments and anthers. The flowers have a delicate, almost ephemeral quality, lasting only a few days to a couple of weeks. The entire inflorescence has a feathery, cloud-like appearance that seems to glow in the dim forest light.

Berries

The fruit is Red Baneberry’s most distinctive and memorable feature. Following pollination, clusters of glossy, bright red berries develop from mid-summer through fall. Each berry is roughly ¼ inch in diameter, contains several seeds, and has an attractive glossy sheen. The berries are borne on thick, often reddish stalks (pedicels) and persist well into autumn, providing color long after most woodland flowers have faded. Important note: All parts of the plant, especially the roots and berries, are highly toxic to humans and most mammals.

Quick Facts

| Scientific Name | Actaea rubra |

| Family | Ranunculaceae (Buttercup) |

| Plant Type | Herbaceous Perennial |

| Mature Height | 1–2 ft |

| Sun Exposure | Part Shade to Full Shade |

| Water Needs | Moderate |

| Bloom Time | April – June |

| Flower Color | White |

| USDA Hardiness Zones | 2–7 |

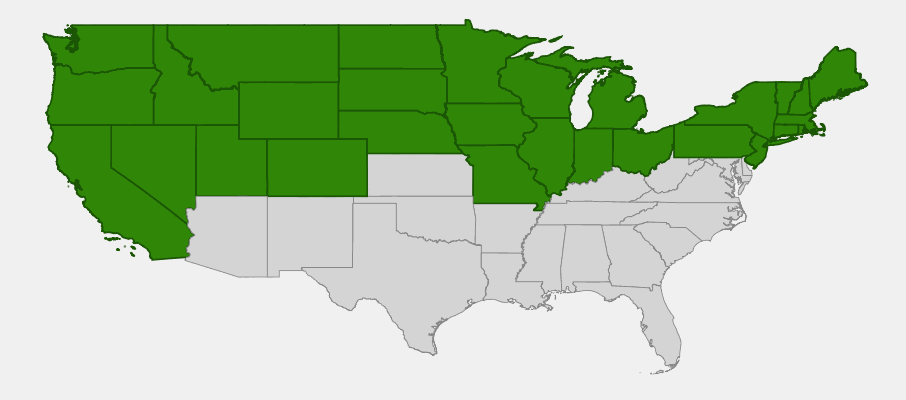

Native Range

Red Baneberry has an extensive circumpolar distribution, native across the cool temperate and boreal regions of North America. Its range extends from Alaska and northern Canada south through the northern United States, with significant populations in the mountainous regions where cooler temperatures and adequate moisture create suitable habitat. The species is particularly common in the Great Lakes region, northern Rocky Mountains, and Pacific Northwest, where it thrives in the understory of mixed coniferous and deciduous forests.

In its native range, Red Baneberry is typically found in rich, moist woodland soils beneath a canopy of trees like Sugar Maple, American Beech, Eastern Hemlock, and various firs and spruces. It shows a strong preference for areas with consistent soil moisture and protection from harsh winds and extreme temperatures. The plant is often associated with other woodland wildflowers such as Trilliums, Wild Ginger, and various ferns, forming part of the characteristic understory plant communities of mature forests.

The species shows remarkable adaptability to elevation, growing from near sea level in northern latitudes to elevations exceeding 9,000 feet in mountainous areas. This broad elevational tolerance reflects its ability to thrive in the cool, moist conditions that characterize both high-latitude and high-elevation environments. Climate change and forest fragmentation pose ongoing challenges to Red Baneberry populations, particularly at the southern edges of its range where warmer, drier conditions are becoming more common.

📋 Regional plant lists featuring Red Baneberry: North Dakota, South Dakota & Western Minnesota

Growing & Care Guide

Red Baneberry is an excellent choice for woodland gardens and shaded landscapes, offering both ornamental value and authentic native character. Once established, it requires minimal care and provides years of seasonal interest through flowers, foliage, and berries.

Light

Red Baneberry thrives in partial shade to full shade conditions, making it ideal for areas that challenge many other garden plants. It performs best with morning sunlight and afternoon shade, or in the dappled light found beneath deciduous trees. Full sun will stress the plant and may cause leaf scorch, particularly in warmer climates. The deeper the shade, the more open and graceful the plant’s growth habit becomes.

Soil & Water

This woodland native requires consistently moist, well-drained soil rich in organic matter. It thrives in soil conditions that mimic the forest floor — slightly acidic to neutral pH (6.0-7.0) with plenty of leaf mold and decomposed organic matter. The soil should never completely dry out, but standing water should be avoided as it can lead to root rot. Regular mulching with leaf mold or compost helps maintain soil moisture and provides ongoing nutrients as it decomposes.

Planting Tips

Red Baneberry is best established from nursery-grown plants rather than wild collection, which can damage natural populations. Plant in spring or early fall, spacing plants 18-24 inches apart to allow for their mature spread. The thick rhizomes appreciate being planted at the same depth they were growing in their containers. Choose the location carefully, as established plants develop extensive root systems and don’t transplant easily.

Pruning & Maintenance

Minimal maintenance is required. Remove spent flower heads if seed production is not desired, though the berries provide significant ornamental value. The foliage may die back naturally in late fall — simply cut back the dead stems to ground level in late winter or early spring. Avoid disturbing the soil around plants, as the rhizomes grow close to the surface and can be damaged by cultivation.

Landscape Uses

Red Baneberry excels in several garden applications:

- Woodland gardens — essential for authentic forest understory plantings

- Shade gardens — provides structure and seasonal interest in low-light areas

- Native plant gardens — supports local ecosystems and wildlife

- Naturalized areas — spreads slowly to form attractive colonies

- Wildlife gardens — berries provide food for birds

- Stream gardens — thrives in moist, shaded riparian areas

- Winter interest — persistent berries provide color in dormant season landscapes

Safety Considerations

All parts of Red Baneberry are highly toxic to humans and most mammals. Plant in areas where children and pets are supervised, and educate family members about the plant’s toxicity. Despite this caution, the plant can be safely included in gardens when appropriate precautions are taken.

Wildlife & Ecological Value

Despite its toxicity to mammals, Red Baneberry plays a valuable ecological role in forest ecosystems, providing food and habitat for various wildlife species while contributing to the complex web of woodland plant communities.

For Birds

Several bird species, including thrushes, vireos, and some warblers, can safely consume Red Baneberry fruits. The bright red berries are particularly attractive to migrating songbirds in late summer and fall, providing important lipid-rich nutrition during energy-demanding migration periods. The persistent berries also serve as emergency food during harsh winter conditions when other food sources may be scarce.

For Mammals

Most mammals avoid Red Baneberry due to its toxicity, which is actually beneficial from an evolutionary perspective — it ensures the berries remain available for bird dispersers rather than being consumed by mammals that don’t effectively distribute the seeds. Occasionally, small mammals may nibble the foliage without apparent harm, possibly obtaining trace nutrients or using it medicinally, though this behavior is not well documented.

For Pollinators

The white flower clusters attract various small pollinators, including native bees, flies, and beetles. The flowers produce both nectar and pollen, with the numerous stamens providing abundant pollen resources. The flowers’ lack of petals and their small size make them particularly attractive to small, specialized pollinators that might be excluded from larger, more complex flowers.

Ecosystem Role

Red Baneberry contributes to forest ecosystem stability through its role in the understory plant community. Its spreading rhizomes help stabilize soil on shaded slopes, while the decomposing foliage adds organic matter to the forest floor. The plant’s association with mycorrhizal fungi helps support the complex fungal networks that connect forest plants and facilitate nutrient exchange. As climate change affects forest composition, Red Baneberry’s tolerance of shade and moisture fluctuations makes it potentially valuable for ecosystem resilience.

Cultural & Historical Uses

Red Baneberry has a complex cultural history, respected by Indigenous peoples for its potent medicinal properties while simultaneously feared for its dangerous toxicity. Various First Nations tribes across its range, including the Ojibwe, Menominee, and northern Plains tribes, had detailed knowledge of the plant’s uses and dangers, incorporating it into their traditional medicine systems with extreme caution and respect.

Traditional uses included preparing very dilute preparations for treating various ailments, including rheumatism, coughs, and women’s health issues. The root was particularly valued, but its preparation required extensive knowledge and experience due to the plant’s toxicity. Many tribes also used the distinctive berries as a source of red dye for decorating clothing, baskets, and ceremonial items, taking advantage of their intense color while avoiding internal consumption.

The plant’s common names reflect both its beauty and its danger. “Baneberry” comes from the Old English “bana,” meaning destroyer or poison, clearly indicating the plant’s toxic reputation. Other historical names include “Snakeberry,” “Necklace Weed,” and “Doll’s Eyes” (though the latter more commonly refers to the closely related white baneberry, Actaea pachypoda). European settlers learned to avoid the berries, though the plant occasionally appeared in early colonial pharmacopeias as an extremely dangerous medicine to be used only by experienced practitioners.

In modern times, Red Baneberry is valued primarily for its ecological and ornamental qualities. Contemporary herbalists generally avoid using the plant due to its unpredictable toxicity levels, focusing instead on safer alternatives. The species has gained renewed attention among native plant enthusiasts and conservation botanists who appreciate its role in maintaining the integrity of forest ecosystems and its value as an indicator of high-quality woodland habitat.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Red Baneberry berries really always red?

While typically bright red, Red Baneberry can occasionally produce white berries in a natural color variant called forma neglecta. This white-berried form is less common but completely natural. The closely related White Baneberry (Actaea pachypoda) consistently produces white berries with distinctive black “eyes” and thick red stems, helping distinguish the two species.

How toxic is Red Baneberry to humans?

All parts of Red Baneberry are highly toxic, with the berries and roots being particularly dangerous. Consuming even small amounts can cause severe symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, and potentially cardiac arrest. The plant should never be consumed, and children should be taught to avoid touching or eating any part of it.

Will Red Baneberry spread aggressively in my garden?

Red Baneberry spreads slowly through underground rhizomes, typically forming small, manageable colonies over many years. It’s not considered invasive or aggressive, and unwanted spread can be easily controlled by dividing clumps or removing offshoots. Most gardeners appreciate its slow, steady expansion in woodland settings.

Can I grow Red Baneberry in a container?

While possible, Red Baneberry is better suited to in-ground planting where its rhizomatous root system can spread naturally. If container growing is necessary, use a large, deep pot with excellent drainage and rich potting mix. Container plants will require more frequent watering and won’t achieve the same mature size as ground-planted specimens.

When should I plant Red Baneberry seeds?

Red Baneberry seeds require a cold, moist stratification period and can take 2-3 years to germinate naturally. Collect fresh seeds in fall and plant immediately in a protected area, or cold-stratify them in the refrigerator for 3-4 months before spring planting. Growing from seed requires patience, so purchasing nursery plants is often more practical for gardeners.

![]()

Looking for a nursery that carries Red Baneberry?

Browse our native plant nursery directory: North Dakota · South Dakota · Minnesota